© 1987 Rich Grzesiak, all rights reserved.

N.B. This was the very first piece I wrote for the now defunct gay newsmagazine Au Courant—and the first full length feature I wrote in Philadelphia after departing the Philadelphia Gay News.

I am not a gay conservative—but I strongly believe that people like Bauman are to be respected, no matter how much one disagrees with their point of view.

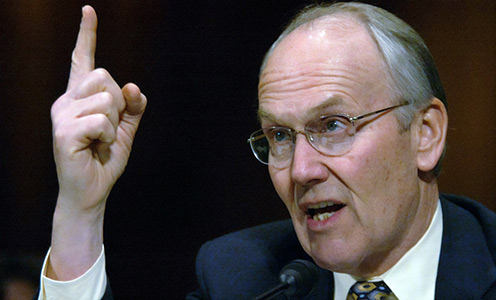

Way back in 1980, Maryland Congressman Bob Bauman was sitting on top of the world.

He was the darling of the so-called "New Right," a neo-conservative movement about to gain ascendancy in American politics. His friends included the arch-conservative writer William F. Buckley and an ex-President by the name of Richard Milhous Nixon. Another friend, former California governor Ronald Reagan, eagerly campaigned for his re-election to a then 5 term career in the U.S. House of Representatives.

Personable and articulate, Bob Bauman was equally at home on the House floor, before TV lights and on the stump. His mastery of Congressional rules and procedures incurred the hatred of liberals for his annoying tendency to block the Carter Administration's key legislative programs (like the now legendary $2/gallon tax on gasoline). Adored by Republican voters, he was often touted as a shoo-in to replace wimpy liberal Maryland Democrat Senator Paul Sarbanes. His family life was impeccable, his wife, a Betty Crocker look alike. His four perfect little children lived with Mommy and Daddy at an historic estate in the eastern shore district of Maryland.

But unknown to the press and public, Bauman's personal life was spinning wildly out of control. His drinking had passed way beyond the just-one-cocktail-at-Happy-Hour stage and, like so many alcoholics, when "totaled" he was fond of jumping into a car (bearing Congressional license plates, no less) and cruising around the streets of Washington at night.

On some evenings, he'd whirl through the gay bars, picking up drinks and hustlers—whom he eagerly shuttled back for a quickie or two.

From House Speaker "Tip" O'Neill to good ol' boy Prez Jimmy Carter himself, the Democrats had no love for right winger Bauman and, when the F.B.I. got wind of his call boy habits, the you-know-what hit the fan. From the White House to the J. Edgar Hoover Building (headquarters of the F.B.I.), the phone lines erupted with the news that one of those a**hole anti-liberal reactionaries was about to take it on the chin.

In September of 1980, after sitting on evidence of Bauman's male call boy solicitation offenses for some seven months, the Carter Administration's Justice Department sent the F.B.I. to visit the cheeky Congressman. They gave him the scare of his proverbial life.

With barely four weeks to go until the general election, Bauman publicly pleaded not guilty to a charge of solicitation—and the media had a feast hanging him out to dry. Strained to the breaking point, Bauman called a press conference where, with his wife looking on, he publicly linked his combined "tendencies" of alcoholism and homosexuality.

The one time shoo-in for re-election not only lost his House seat (by a surprisingly narrow margin), but, during the next four years, his marriage and his career. When you ask him about it, the anguish you see mirrored in his face tells you all.

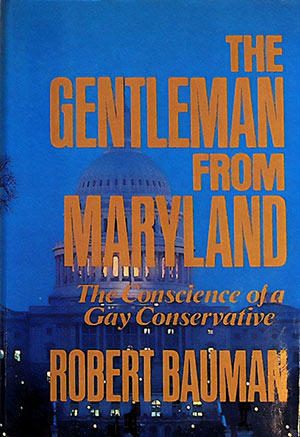

Recently Bauman has written a gutsy, shocking autobiography that names names and states facts. Entitled The Gentleman from Maryland: The Conscience of a Gay Conservative [Arbor House; $17.95/hardcover], it's been the talk of the gay political circuit for months on end.

Bauman comes across as an intense, elegant, debonair man who seems just like the guy you'd want as your favorite brunch guest. I hosted him in September, 1986, and, during a wide-ranging interview we discussed, among other things, his sympatico "friend," Rep. Barney Frank (D-MA), his hostility to ultra-liberal gay leaders, the future of gay conservativism, his fall from power, the Reagan Administration's AIDS policies, his battle with alcoholism, why he doesn't like being gay—and, among other things, his ideas for a "common cause" approach to gay liberationism.

There's been a terrifying silence in the gay community about its conservatives; some have been virtually black-listed from gay political organizations (in a style reminiscent of McCarthy and Stalin) because of their right wing views.

That's one dirty little secret and so, like Lestoil and dirt, I and Bauman got down to business real quick.

Here's how it went:

Rich Grzesiak (RG): You've lost your House seat and your credentials as a New Right spokesman; your family has paid a terrible price because of your tragedy. Given the benefit of hindsight, what would you do differently today?

Bob Bauman (BB): Beginning when—the day I was born?

I was ill-equipped [in 1980] to deal with my situation . I was largely dependent on political advisers who had little or no knowledge about homosexuality or alcoholism. They knew a lot about politics and about what was the best way to handle a disastrous situation. There were those who said contain it—others said let it all hang out, the people will judge.

Looking back, I could not have done much other than what I did do[but] I should have been much more forthcoming. One of the major impressions that augmented the valid charge of [my] hypocrisy was that I was using alcoholism as an excuse for homosexual activity. In a column at that time Bill Buckley theorized that once I stopped drinking I was no longer gay, [a charge] which led to a public difference of opinion between us, although we still are good friends.

I should have been far franker in dealing with my homosexuality which, at that time, I didn't accept or understand fully. I should have explained the relationship of my homosexuality to my very real alcoholism, which, in fact, many gays suffer from.

RG: If this episode were to happen today, would the reaction of the conservative electorate on Maryland's Eastern Shore be different?

BB: Yes, I think there's an educational process that results from major upheavals like these. As one of my constituents was quoted as saying, "If he could be one [gay], anyone could be one—it makes you wonder." They now know that Congressmen can be people they admire, vote for, agree with and also homosexual.

In Maryland right now there are a number of gay people running for office. They're not out of the closet, and they're likely to be elected. Sub rosa, there are certain comments made, but people are more accepting today.

RG: A friend suggests that had there been no Bob Bauman, there would have been no chance for either Congressmen Studds or Frank to be open about their private lives.

BB: It would be egotistically nice to agree with your friend's premise, but Studds was elected on his own reputation as a good constituents' service Congressman that out-weighed his homosexual affair 10 years before with a Congressional page.

If, like Studds, I had had a year and a half to explain [my problems] to my constituency, conceivably I could have been re-elected.

RG: If you were a political consultant, and an elected official came to you and indicated they were gay, what would be your advice?

BB: I was mercilessly grilled by a TV interviewer several years ago—one of the viewers that night was a young state legislator. He was conservative, wanted to run for Congress, belonged to the right party in his state, had no family to speak of. We met later and he asked my advice.

I told him that given the conservative environment in his state, he could not possibly hope to succeed—he'd suffer the same fate I did I advised him to either get out of politics or come out openly.

He chose to get out of politics—he decided it was too great a burden for his political career.

But my general advice to anyone in that situation is to come out if it's at all feasible; if you don't, you can expect the worst.

RG: You've made statements implying that liberal Congressman Barney Frank (D-MA) is gay. Do you have proof?

BB: I don't wish to comment about my friend Barney Frank in any way beyond what I said in the book except to say that it was a mistake for me to perhaps mention his name.

RG: You made conflicting statements about the Carter Administration in your book. On the one hand, you condemn them for "fingering you" over your difficulties; on the other hand, you claim that "any political animal who would fail to come down on such a vulnerable adversary" would be foolish. How do you reconcile these seeming contradictions?

BB: There's no need to reconcile the two because it's all nasty politics. Both statements are partially correct and can be read together.

I did indeed violate the law and one has to accept the consequences. My complaint was/is that there were nine other members of Congress who were known to be engaged in similar conduct and none of them faced the legal wrath of the Carter Administration; some of them are still in Congress; a few I've seen in gay bars.

The investigation into my case was completed in February of 1980, but nothing was done about it until September. The timing maximized the damage to my chances for re-election.

Unlike the other nine, I was a greater irritant to the Carter Administration, liberals, and House Speaker "Tip" O'Neill. Remember that I [sponsored legislation which] abolished Carter's expense account, which he was using as income, and I forced the Justice Department to open its investigatory files on Billy Carter and the Libyan oil deal.

Now, if somebody from the Justice Department calls the President and says, "We've got this Bauman dead to rights—he's been seen in gay bars soliciting sex," well, what do you expect?

That's politics. I gave them plenty to work with.

RG: You told The Washington Blade, "I'd rather not be gay." As a result, gay activists have been severely critical of your attitude toward homosexuality.

BB: I'd rather not be gay ; I reiterate that.

RG: But what you're saying by that is that you want people to accept things that you would prefer not to be.

BB: Well, I can't cure being gay, but, in the context of my life, had I a choice, which none of us really have, I would have said spare me this, I have four children who are embarrassed by it and will live with this stigma to the grave. I've lost a wife, who has suffered greatly at my hands.

What did I do to a good woman who believed and loved me? What did I do to four children whose lives were destroyed as they knew it? They were confronted with a tragedy that most people don't have to deal with.

So, yes, I'd rather not be gay. Do I think that [being] gay is any less human or important? No.

Gays are just like anyone else with the exception of their sexuality. But I've had a lot of gay people come up to me and say, "You know you're right—a lot of us won't admit it, but, if there was a Pill [to change one's sexuality], I would have taken it."

It would be a whole lot easier in this society at this time if I were not gay.

RG: How has your family reacted to the publication of your book?

BB: I cannot and will not speak for my ex-wife. It's been tough on my children, but all have indicated some degree of understanding. They would have rather not had to face the book, as it re-opens some questions—it's been a trial.

RG: Do you think you've been fairly treated by gay leaders?

BB: I have no complaint against gay leaders except that they're too damn liberal.

I'm an accident of fate in that I was forced out of the closet. I don't pretend to leadership in the gay movement—I reiterate that I admire those who have fought the battles against anti-gay discrimination since Stonewall. My only complaint is that the times are changing and these leaders ought to change a little bit too [by being] broader in their views.

I do resent people saying, what right do you have to write a book about being gay—you're a conservative! Of all the groups in this country that ought to understand tolerance and [the] practice of anti-discrimination, gays should be at the top of the list. If they can't understand that it's possible to be conservative and gay, they ought to look in the mirror.

RG: The reaction of the gay press to your book has been severely critical, as have been some of the mainstream papers. The Philadelphia Inquirer's critic uncharitably said, "We can forgive but we cannot afford to forget."

BB: Not so, not so! It's gotten good reviews from the Wall Street Journal, the Washington Post, the Chicago Tribune, the Christian Science Monitor; all these praised it for candor and openness "from a right wing ideologue like Bauman."

RG: One Philadelphia gay reviewer had the cruelty to imply that you haven't "grown" in that you have not repudiated your ideology and religion [Catholicism].

BB: Bullshit! That's what I got from a lot of gay leaders who have made a feast over the years of leading gays into good areas and some bad ones.

Writer Darryl Yates-Rist told me recently, "I don't agree with you on anything politically but I agree on your tactics. The time has come for the gay movement, if it's going to succeed politically, given the problems of AIDS and demagoguery from the right, to make common cause. We don't need to fight less, but we don't need to be so blatant [in our internal squabbles] as we have in the past."

Maybe that's not a view shared by most gay leaders. But to say to me that I have to stop opposing abortion, being anti-Communist, and supporting a balanced budget in order to gain credentials for being gay is, I repeat, bullshit! I don't buy it. The mass of gay voters in this country are not raving liberals who are comfortable marching down the streets of San Francisco with a Socialist Workers Party that advocates the overthrow of the U.S. government.

RG: In your book, you allude to the founding of C.A.I.R. [Concerned Activists for Individual Rights], a gay conservative lobby which hoped to compete with the rabidly leftist politics of unpopular gay leaders. That's a commonly held, popular sentiment. So why, then, did C.A.I.R. fail amid the rising tide of conservatism both within/without the gay community?

BB: Because the average conservative gay, particularly if they're in government at any level, knows that the same thing that happened to me will happen to them. The instances are rare when a conservative acknowledges being gay—they fear even more the reaction of their colleagues than they do the outside.

I can criticize the liberals for their tactics in the gay movement as well as their pretension to speak for all gays on issues ranging from Nicaragua to welfare. I can also say that they get all the credit for leading this community since the Stonewall days. [By contrast] Conservative gays have been willing to reap the benefits of their ideology and at the same time enjoy a private lifestyle while paying none of the price.

In C.A.I.R. we found that we could attract many gays and lesbians, some on the staffs of the most conservative Congressmen, Senators and even the President, but [when we asked them to lend their support] by signing a statement, only one person other than Bob Bauman was willing to say yes. They didn't even want their names on a secret mailing list. [Their attitude was] "Please, we'll give you cash, but we don't want to give you a check."

RG: How would you assess the political strength of the gay community?

BB: It's considerable and [given certain close races] it's decisive. If gays voted as a political unit, they could make the difference in major statewide races.

In California, the very close U.S. Senatorial race between incumbent Sen. Cranston (D-CA) and Rep. Zschau (R-CA) may be decided by the gay community. Cranston has been a longstanding supporter of gay rights. In races like that, [gays] could decide the control of the U.S. Senate. In places like Houston, San Francisco and New York City, gays could prove to be the crucial influence in key races.

By and large, the Republicans in the last few years have learned that you have to stop gay baiting—the only people doing that anymore are the radical right.

RG: If you were still in Congress, would you be willing to co-sponsor the federal gay rights bill?

BB: I certainly would. I would vote and speak in favor of gay rights in Congress. I think it's a shame that I had to be educated to that position in the way that I was

There is even a moderating trend among conservatives on this issue. It's surprising that, despite the AIDS problem, you'd expect a harsher and more demagogic treatment from the right [regarding AIDS]. Strangely enough, exploitation of AIDS has been left to the real nuts like LaRouche. Shortly before the election in November, 1986, I wouldn't be surprised to see President Reagan himself come out against the LaRouche referendum in California [requiring the quarantining of AIDS patients]. [Editor's note: Reagan did not publicly oppose this referendum, and it was roundly defeated during that election].

RG: How do you evaluate Reagan's stance on gay issues? Some gay "leaders" charge that his Administration has not provided enough money for AIDS research.

BB: I think that that was an issue manufactured by the professional gay liberal leaders. Almost three years ago I talked to a liberal, anti-Reagan public TV producer who had just completed a documentary on AIDS. He had been to the C.D.C. [(U.S.) Center for Disease Control] in Atlanta; he filmed all around the country. He told me that he didn't think more money could be intelligently spent.

If money could solve the AIDS problem, the hundreds of millions that have been spent could have gotten us further along—there's enough leeway to say that maybe money alone couldn't solve this crisis.

But I fault the Reagan Administration and the President for allowing homophobes to make [federal AIDS] policy. I personally don't think the President is anti-gay, as his position on the Briggs referendum [to fire gay California school teachers] proves.

That probably mirrors his live-and-let-live attitude. After all, you can't be President of the Screen Actors Guild and not know a lot of gay people. Gays visit the White House, the Reagans call Rock Hudson when he's dying of AIDS—some other president couldn't have done that.

Yet he allows some idiot at [the Department of] Justice to issue an opinion on AIDS discrimination that is right out of the Middle Ages—that's where I fault Reagan.

RG: Almost a year ago the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the state of Georgia's anti-sodomy statutes. Conservatives have traditionally argued that the state has an interest in enforcing certain moralities. As a conservative, what do you make of the court's ruling?

BB: It has been traditional since the origins of English common law for the crown, the parliament, the state legislatures, the Congress, to express in law the moral standards of the society they represent. Anti-sodomy laws go back hundreds of years.

What a person does in the privacy of his own bedroom is no business of government. That's a majority viewpoint these days. Many, many states have already repealed their anti-sodomy statutes. The High Court made its decision by a narrow 5-4 vote on a privacy case which, given the technicalities, could have gone the other way. I think the Supreme Court will reverse itself in the next several years.

This country does not support anti-sodomy laws because they intrude into private lives

RG: Is there any political future for ex-Congressman Bob Bauman?

BB: I'd love to be back in Congress[but] I have to take one day at a time. I'm an alcoholic; I face a lot of problems that everybody shares. Politics interferes with self-control and serenity.

I pretend to no political future; no one is going to hand me a presidential appointment. I will be content to find another person in life that I can make a home with and to see my children achieve success.

I'm a person with very simple needs.