© 1987 Rich Grzesiak, all rights reserved.

"Truman and I were never together—together people as most couples are. Such proximity would have killed us. We were always dreaming away from wherever we were, thus repeating the pattern that had commenced in childhood, when one's need to escape from one's own kind was so savage, so burning in its intensity, that had either of us stayed home, he would certainly have perished." —from Jack Dunphy's Dear Genius: A Memoir of My Life with Truman Capote

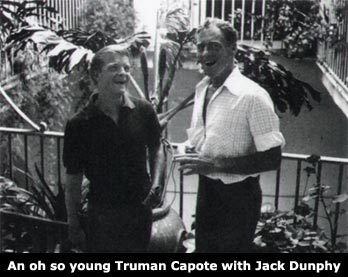

When I caught up with Jack Dunphy, the late Truman Capote's lover of some thirty years, it was one of those pedestrian moments every interviewer hates: he was distracted, eating a morsel of chocolate, evidencing some nervousness about talking to a "gay" newsmagazine, all the while protesting that he loved talking on the telephone, later moaning about how glad he was that he didn't have a phone to bother him at his apartment in Switzerland.

And then we began The Interviewing Game, I projecting earnest professional politeness, he brandishing The Attitude where wariness of journalists is very much a part of social rules. But when we got that out of our system(s), he began lecturing. "You'll have to forgive me," he ordered, "whenever I used to talk to Truman I'd have the habit of repeating things like 'I see' or 'you understand.' And he'd come right back at me and say: 'Yes, I see you, I understand, I hear you get what I mean ? "

Dunphy: "I hate words like 'right'—they're conversation cutters. You begin to tell someone the story of your life and they come back at you with 'right ? '"

Right. Know what I'm saying—Get what I mean—Dunphy then followed with a short sermon on People Who Think They Know All about Creative Life but Don't Know A Fucking Thing.

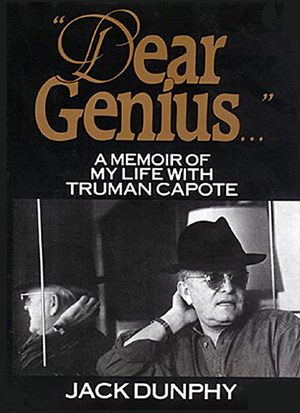

Not being able to cut through the at times obdurate Dunphyian social patter, I tried to swing the conversation back to where I thought we should start, namely complements on Dunphy's memoir of his 30 year friendship/relationship with the author of Breakfast at Tiffany's, In Cold Blood, and Other Voices, Other Rooms, a strange new book bearing the odd title of Dear Genius: A Memoir of My Life with Truman Capote [McGraw Hill; $17.95/hardcover]. It's a book that could have been an important new chapter on Capote's life, revealing the intimate details of a fascinating relationship. Even writer Donald Windham, who has written widely about his own tremendous falling out with the "Tiny Terror," has a high regard for this book, praising Dear Genius for "showing us the Truman that we knew." Does it?

Dear Genius tries desperately to show us the Truman that his lover's personality can only struggle to know. In often uncomprehending, even stony tones, Dunphy artfully constructs his version of what Capote meant to him: we get juicy hot flashes of the Capote temperament, yet mainly we are surrounded by suffocating sections of invented characters and plot, most of which obscure the answer to the question readers want to know, what in the name of god was it like to live with Truman Capote, literary lion, one of this century's most public personalities, darling to the best people, and, in his later years, addict and alcoholic—Dunphy weaves a vanilla prose which with rare instances almost threatens to bleed the life out of the Capote we really want to learn more about.

So, finding so little red meat in Dunphy's bloodless book, I asked about the Capote the media had portrayed with a cruel honesty. The Public Broadcasting System, for example, recently aired an entry in its American Masters series which attempted in one hour to make sober sense of the late writer's tangled life. The cinema verite style documentary was called "Unanswered Prayers," a pun on TC's seemingly unfinished novel of jet set scandal.

"I really think that the title of that damn show was terribly presumptuous!" Dunphy spat out, sounding angry, unsettled, as he often will in response to my questions: "If anybody's prayers in this life were answered, Truman's certainly were! Who the hell can say that he didn't live a fulfilling life, with such beautiful books as he produced ? That's why the so-called professionals won't appreciate my book on Truman. They want to get the dirty things or the gay life—whatever that is."

But why does he want to withhold so much information on Capote's life, I feel like asking, yet I can think only of the sad, sorry, almost grieving look on Dunphy's face during his own telecast appearance on "Unanswered Prayers." So we discuss instead what will eventually become the most elusive aspect of Dunphy's own character, his feelings.

When Dunphy begins to talk during the documentary about the man he lived with for 30 years, the astute observer can see that it's a painful process for him, that in fact his eyes begin to well up with tears. When I confronted him with that observation, Dunphy's reaction was as typical as it was immediate: he became very defensive, explaining that he was ashamed to be on the "damn thing, as I don't like TV, and if you saw tears there, as I said to George Plimpton, they were tears of shame from even being there. TV out-Hitlers anything Hitler ever did: it tells you what to do, what to buy."

"Yet I used to like talking about Truman," he admits, "especially to total strangers who would always interrupt me. Now I don't know." Reminiscing about his late friend "just gives me an emotional hangover unless of course I begin to talk about Truman as I do in the book, when it was a pleasure and fun" to be around him.

The late writer was a generous soul, as far as companion Dunphy was concerned. He deeded a house at Sagoponack, Long Island to him and, even more importantly, there were moments when, in the wild extravaganza that Capote's life became after In Cold Blood, especially in the 1960's, they shared many private, richly filled hours, in Manhattan, in Switzerland, and around the world.

And again, when I asked Dunphy what Capote was like when he first met him, his reaction typified our conversation: he became immediately defensive and, sniped at me with comments like, "Well, you want me to tell you things you already know, or should know if you read the book."

But I want to hear about it in Dunphy's own words, I counter. "Well, you make me feel like an old Billy Holiday record," he says, sounding just like a bitter old queen.

Yet ultimately, as Dunphy freely admits, "talking about Truman really makes me very emotional and it's difficult for me, I really can't. I have to work myself up to it." But what I encountered was just a front, a mask of a very difficult, seemingly avuncular man.

Perhaps that's because that there is so much unpleasantness to hide. Capote could be very nasty to people, especially in his declining years. Dunphy claims that he was aware of the many sides to the writer's personality, including the darker ones, but that these were held in check for the most part when they were together. He's proud of the recollection "that I never lost myself in him, as so many people do in relationships: they tend to lose themselves in the other person, to become one, I was very different from him. He would always accuse me of never spending money, which he loved doing. Another thing that greatly helped" their thirty years together "is that I never wanted what Truman wanted. Although we lived together, we lived rather separate lives. For instance, I would like to go to a Shakespearean production," yet Dunphy could never get his writer-friend to attend.

I told Dunphy that my major impression of his deceased companion was that he was a very emotional person, someone who found it easy to express his feelings for other people, yet tragically, ironically starved for affection in his own life. Very deliberately, I observed that "certainly he got that from you."

"Did he ? " Dunphy asked me. "I really don't know. I'm not a very outward person. For instance, my family never kissed or anything like that." The most emotional thing Dunphy will admit from his own past relationships concerned the day when, very young and freezing from the snow, he entered his parent's house and his mother, in a spontaneous burst of emotion, allowed him to put his freezing hands beneath her armpits.

I was startled by that admission, that self-knowledge of a type of personality I myself have always been drawn to but rarely understand: the self-assured, strong man who winds up being the protector in a relationship, but finds himself unable to show his feelings to significant others, even those closest to him. How did Capote, emotional person that he was, cope in a world where even his closest friend, his most intimate companion, the man he "only had eyes for," found it difficult to give him even so much as a peck on the cheek?

Suddenly, the years of pain that Capote endured, the eventually endless treks in and out of addiction rehabilitation programs and hospitals, made a strange, sick, painful kind of sense.

Truman Capote, the tormented genius tortured by addiction. Not so mysteriously, Dunphy claims he hated "drunkenness in other people in a very, very subjective way. I've never met anyone who so hated it, probably because his mother was an alcoholic."

Dunphy: "You know, there are whole stretches of Truman's life that I don't even know anything about. I was not like Frank Merlo, Tennessee Williams' lover," a gay man who implicitly encounters Dunphy's derision for having "lost himself" in that great playwright's feelings. No, Dunphy was "too egotistical, too self-centered for something like that."

Today he realizes that Capote's regard for him was so high that he placed him far above other people, so far in fact that had Dunphy realized it at the time "I would have been overwhelmed by it."

I asked his lover why Capote was never successful in dealing with his addiction problems. His answer was typical, a long commentary on the complicated nature of addiction and the profitable commerce that keeps the liquor and drug companies going strong. He reminisced about the great English art historian Sir Kenneth Clark, whose wife was an alcoholic. For them and the outside world, the whole issue of her drinking was heavily linked with the attitude of denial: oh, we're doing all right, oh yes, we'll go back to what we were. I could almost hear Dunphy shuddering when he talked about Clark's fetching a martini for his wife in the morning, something he claims he could never do for Capote. "Clark once said that he would rather have his wife drunk than grouchy, and yet I could never say that about Truman. He just couldn't drink."

There are sections in Dear Genius where Dunphy berates Capote for his drinking as well as poignant recollections of Capote's entering this or that hospital, here and abroad, usually for exhaustion, fatigue or other imagined "illnesses," all of them in the final analysis nothing more than symptoms of his unconquerable disease. What disturbs me about Dunphy's behavior is that, in spite of his protestations to the contrary, his actions evidence very much those of a man codependent on Capote's declining health. "I hated it that he was wrecking himself and all," he says.

But was alcohol the only thing wrecking Capote ? Dunphy: "I often thought of Truman who was, as an artist, someone who was truly classless and outside of society. He should have distanced himself from them, not let those people hurt him. Of course he didn't," and they caused him great pain.

The pain Dunphy refers to concerned high society's reaction to Capote's Answered Prayers, a scandalous semi-fictionalization of the jet set's never ending comedy of manners. "Truman loved beauty: those people could always have the best. That's what drew him to them."

Were Capote's painfully declining years really the result of his literary success coming at such an early age (his first short stories emerged when he was 18) ? Dunphy dismisses that theory, claiming that with the exception of Verdi, whose last opera was produced when he was 80, the end of "all creative lives are miserable things. Your creative powers are declining, the things that you do best are harder to do. What greater misery can there be ? "

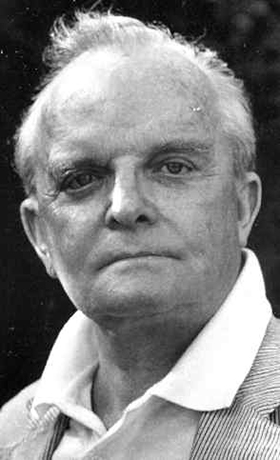

That misery must have intensified for Capote as the years grew, because he never really hid himself from the world. His frog like, ravaged face was all over the place, from The Tonight Show to the film Murder by Death, where he unashamedly throws his Southern fey/gay manner at the screen for all the world to see. According to Dunphy, that openness could not permit his embrace of things like the gay movement, because the two of them were openly contemptuous of things like that: it perhaps made them squirm to see so much sentiment in the air, even in a political context.

Finally, Dunphy seems not to have been very close to Capote in his last three years. He claims that Truman was very strong, had very "strong legs," and his death (1984) took him totally by surprise. Is it any accident that he died in a house owned by one of Johnny Carson's ex-wives, in California, a state where, in Capote's words, "the wind through the winter says sleep"?

May he rest in peace.

This was probably one of the most difficult interviews I ever conducted: my interviewee spoke to me with great reluctance. I'm referring to Jack Dunphy, Truman Capote's "lover." As you read this piece, bear in mind that Capote's addiction issues were not widely discussed in the gay press with any degree of seriousness, let alone understanding, circa 1987.—RG