© 1993 Rich Grzesiak, all rights reserved.

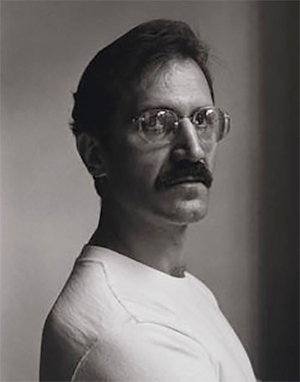

When Manhattan writer Darrell Yates Rist set out on a journey across gay America, readers familiar with his background might have quickly moved to another tome. After all, Rist's writing during the eighties was polemical if not shrill: his manner made the dyspeptic Larry Kramer seem like Connie Chung.

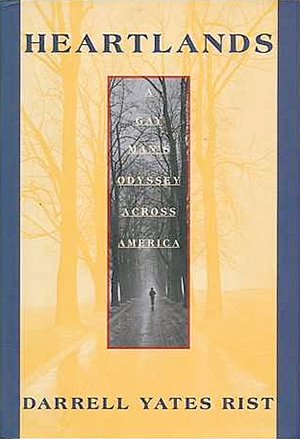

Rist's journey yielded a highly readable travelogue entitled Heartlands: A Gay Man's Odyssey Across America [Dutton; $24/hardcover], probably the best if not the most authentic, emotional, heartrending, eloquent look at that undefinable commodity known as "gay America" ever written. Other attempts to tackle this subject have entangled the talents of every gay writer from Edmund White to Neil Miller to John Preston, all of whom fail when compared to this brown shoe, shit kicking travelogue-cum-memoir.

Rist began his participation in the gay movement as a co-founder of GLAAD, a group which he now regards as well intentioned but misguided. Like many before him, their fiery rhetoric eventually proved tiresome. He found himself wondering why people committed to idealism were as ironically narrow minded as those homophobes whose intolerance they battled.

In later years, stultified by the emptiness of gay New York and emboldened by a sudden remission from a year's battle with AIDS, Rist headed out on a 100,000 mile trek down the "blue highways" of gay life. Heartlands may be read as richly detailed travel writing on one level but also as one of the most evocative explorations of gay identity ever published in these United States. Far more discerning than White's States of Desire (1980) and certainly better written than journalist Neil Miller's anemic In Search of Gay America (1989), Rist's observations will rattle the politically orthodox among gay writers, editors, and activists (all of whom could well sustain an intellectual enema at least once a year). His notions on what "gay" is, what a gay community represents, and the value of the American gay identity are radically compelling far beyond the lingua franca of accepted community norms.

When Rist reached the Ozarks, he entered a house where a needlepoint wall hanging commemorated the following words: "I like to see a man proud of the place in which he lives. I like to see a man live so that his place will be proud of him."

The writer was Abraham Lincoln. The motto should be emblazoned over every gay bar.

We talked for what seemed forever, and these are the highpoints of our discussion:

Rich Grzesiak (RG): New York is where all the fringes of art combine to form One Giant Fringe, an urban "surrey with the 'fringe' on top," the stereotyped gay Manhattan ghetto which passes for Baghdad on the Hudson New York writers who praised Heartlands missed its point: Edmund White thinks you've focused on a dissection of the pain of AIDS while Doctor Duberman suddenly discovered there's a real gay community which wants nothing to do with the ghetto.

Darrell Yates-Rist (DYR): AIDS is portrayed poignantly in Heartlands but it defies what urban America has constructed AIDS to be. New York and all the major cities with gay concentrations have a narrow minded delusional gay identity where the current concerns of these white, middle to upper middle class, well educated men get together and define what homosexual ought to be.

They define it by the standard of the way they live. So what affects them should be the concerns of all America. They claim in the AIDS epidemic that because in the gay ghettos many of their friends are dying, and no one denies the tragedy of it, they can go on to claim that that is the only issue: their issues are the only issues.

When you get into middle America or out into the real world, period, you find that the health issues in America are not just AIDS: there are lives being destroyed by other diseases. The failure of the health care system in America does not just affect gay men.

When you ask same sex practitioners out in the middle of the country, their major issue is not AIDS. AIDS has affected men in Tupelo, Mississippi, as I wrote about. I visited a young couple in Tupelo both of whom had AIDS. They were determined to live, wanted a cure, were willing to participate in lobbying for a cure, but they also lived among their non-gay neighbors where they understood that the hardships of life are not limited to AIDS and being gay.

RG: I'm glad you've reached that point of view. It's good people are broadening their vision beyond the politically narrow ones so in vogue in certain gay leadership cliques. It's good people are understanding their lives need to be whole and not just focused on their genitals.

DYR: and claim their own difficulties are the only ones. In the bayou of Louisiana, I stayed with an alligator trapper who is Cajun: he came from a very poor culture, was virtually illiterate, was still working with his father and mother as a trapper. They could barely pay the phone bill and worked very, very hard.

I trapped with him for a week and got a sense of what his day was like: up at 3 in the morning, out to the very chilly bay. He described fishing there in January and February where the wind turned you into living icebergs. They lived in a house that was barely more than a shack. His main difficulty in life was not dealing with gay identity or How Much Like New York Gay Men He Was --- his problem was surviving economically, culturally. It was a brutal existence.

He had learned how to deal with his sexuality and accommodate himself to the culture he lived in. He was learning how to survive economically even though it was very hard. He probably will never leave that situation because he didn't have an education.

What his life demonstrated was even though we must recognize homophobia, the government's inaction on AIDS and the injustice which has been meted out during the epidemic, we sometimes have to stop just whining and saying 'me, me, me' and realize injustice in life is sort of a given. We can work to change it but we can't lie down in the middle of the street and have temper tantrums to say "I'm the one who suffers more than anyone else." You have to learn to live your life to survive and overcome.

If Life Is Hard, well, life is hard, and it's not going to get much easier for any of us. I have to learn how to triumph and live a fulfilled life in spite of all those problems. I think people outside the gay ghettos have a better sense of that than the people who dwell in them.

RG: In the last 15 years I've interviewed the Bob Damrons and Edmund Whites and Neil Millers and John Prestons who have journeyed across gay America. They were imitation deTocquevilles who wanted to document sex, culture, reality and community, respectively, and all missed the mark, despite the praise I and others, blind at the time, heaped on them. Heartlands seems to be the first such memoir/travelogue which reaches beyond the highways, byways and folks to the soul of gay America.

You write, "There's no geography as desolate as the mind." That's what these others travelers missed: they forgot the spirit of the people: their souls.

DYR: In discovering the soul of gay America what you actually have to open yourself up to is the soul of America, which is the soul of humanity. I don't mean that to sound cliched or forced and overly grandiose. I was so disillusioned with the gay life I was living, with the assumptions about homosexuality, who was gay and who wasn't, who was self loathing and who was self accepting. I won't say my open mind necessarily came from an open impulse: it was sheer necessity. I was broken when I left Manhattan to do this trip.

What I wanted was a journey of self discovery as much as a noble journey of trying to reveal the soul of gay America. When I got out into the hinterlands where the real people who were not all socially and politically constructed lived, I found their lives are not like those of gay activists or gay identified men in the city. They share their lives with their neighbors; they don't have a lot of gay men to associate with. So they must learn to deal with people they attend church with and their families.

One of the problems with the gay soul as we have come to understand it is that it's a soul in exile. A lot of us went to the big cities because we couldn't get along with our parents. Some of us went to urban America for legitimate reasons: some had difficult times surviving in the bayou of Louisiana so we escaped.

But when we fled to the gay ghetto we no longer had to deal with the real world. Those others out there were learning that they still could insist on being open about their same sex relationships, knew that there would be occasional if not frequent difficulties, but learned somehow to accommodate themselves to the culture in which they lived.

It seemed to me the gay soul was more at peace with itself in these areas we sometimes called godforsaken parts of America. There's a lesson there: you can't make up gay identities in the big cities and say that they're natural identities which homosexuality requires us to acquire.

A lot of the men I met in New Mexico and Alaska didn't even consider themselves gay, yet they were very open about their same sex relationships. What they said was, "My identity is with the culture in which I live, not with other gay men."

One gay man in Alaska startled me by observing, "Essentially homosexuality or heterosexuality, gay or straight, is not the issue here. When you move to Alaska they're not so concerned about who you sleep with. What they ask you first is, 'How well do you hunt and fish'"?

Hunting and fishing there represent survival It's not whom you sleep with there, it's how much you contribute to your community.

I'm not naive: I realize there are places in America where people don't let you forget you're in a same sex relationship. In many places the homophobia can be enormously brutal. Yet even there, I found men who stood up proudly, not necessarily claiming gay pride but pride as a human being. And they survived.

In Vincennes, Indiana, the local thespian society held a party which a number of gay men attended. There was a non-gay man present who, after the party, was found dead in a ditch. The local D.A., a right wing maniac, began orating about why this large gay party was full of drugs and a death cult The local paper printed names of people at that party and several gay men committed suicide as a result. Others lost their jobs and were forced out of town.

No one denies the Nazi like horror of that But the weather man on the local TV station, known to be gay, also attended that party, and testified at the grand jury. This TV weathercaster was that rare soul, who, unlike most gays in Vincennes, stood up and said, Yes, I am gay People had learned to love him there as he grew up in that community where he had been openly gay most of his life. Because of his pride he continued in his job. In the ensuing years he would get all kinds of phone calls at this country TV station from farm women and grandmothers who would say, "I think my son's gay and I want to talk to you about it."

So there's a way we can learn to survive even in the worst of circumstances. Of course, I'm not sure living in an isolated gay ghetto is the way to survive. The anti-gay violence in big cities is often worse than in the outback of Mississippi.

RG: The politically savvy wisdom is that we avoid violence in the womb of the gay urban areas.

DYR: A gay cable interviewer commented that it seemed like I was saying people in the hinterlands could survive because they knew their place. He asked if there was so much tolerance, could gay men walk down the street hand in hand?

Freedom is a relative thing for all of us: blacks, Jews and women understand that. Every one of us has some characteristic we have to be cautious about in order to accommodate ourselves to this society. The delusion is that the gay ghettos of America promise some absolute freedom.

Certainly, in the Castro the likelihood is you can walk down the street arm in arm with your lover, but if you do that in Greenwich Village you're asking to have your head bashed in.

My point is it isn't perfect anywhere. We have to always aggressively push the limits of tolerance and try to reform things. The absurdity is we have convinced ourselves there's freedom only in the big cities. The epidemic of anti-gay violence is far worse in San Francisco and Los Angeles than it is in rural Alabama.

We must get rid of our mythology and delusions before we even know how to construct a gay politics.

RG: I respect gay leaders in Los Angeles; I think they lead the pack of their peers in engineering political progress for their constituents. But many urban gay "leaders" elsewhere are phantoms who represent no one but themselves, so they never get anything done but alienation. Gay Philadelphia epitomizes such a phenomenon. The gay ghetto is not world famous in acculturating gay leadership skills.

DYR: Many folks entered the gay movement with a grand fantasy of who our brothers were and the Goodness of Gay People: Straight People Were the Oppressors, We Were the Freedom Lovers.

RG: I began in the gay movement as a liberal democrat expecting a social democrat's approach to gay liberation. I wound up being a moderate gay rights centrist repelled by a radical agenda for unthinking social change.

DYR: The problem with the gay movement is it's by and large delusional. Some years ago I joined a gay organizing committee for another march after the historic Gay March on Washington of the mid-eighties It's shocking to learn how narrow and tight the gay activist world is. What startles me was I actually knew most folks at that meeting. How representative can such groups be if I as white, middle gay person, know everyone who's there?

So I asked what about the men and women who lived beyond the world of gay activism? When I suggested we get the input of rural gays, they laughed at me. No one wished to relinquish their power.

The gay movement has carved out an enormous geography of power, all in the hands of relatively few people.

RG: I note you have ratified Gore Vidal's point in The City and the Pillar if not innumerable essays over the years: there is no such thing as a homosexual. He wrote you "found "no gays only men" in your journeys across America: men in the true sense of the word, not Drummer-esque parodies but people of substance and depth and ethics. Is Vidal right?

DYR: Vidal's wisdom has been so radical ever since 1948. The interesting thing is how much his sexual views are either ignored or chuckled about. If the gay movement really took Vidal seriously, they'd take many a pot shot at him.

I visited a white potter outside Santa Fe, New Mexico where I kept using the word "gay": how I wanted to meet gay Hispanics, etc. He exercised extreme patience with me til he finally admonished, "You keep saying, 'gay, gay, gay.' What you need to understand as an urbanite is that 'gay' is a term of privilege. 'Gay' identity is something that you can put on to isolate yourself as a distinct kind of person: if you're economically well off, if you no longer need the emotional/financial support of your family, community and church. The men I know in New Mexico don't have that advantage. Their families may know they're in a same sex relationship and may even accept that."

"These men can't afford to take on an alienating identity which says, 'Yes I grew up in this family but I'm really not like you, I'm like what the gay activists say I am, a complete and distinct character, another breed of human being."

Gore Vidal has been eloquent about this. People see him as the elder curmudgeon of America and not always to be taken with absolute seriousness. Yet what he says is devastating to both heterosexual assumptions of gays as well as gays' assumptions of themselves: no one has been more right about this issue all along.

RG: The most basic revolution gays need to confront about themselves in the nineties is that our differences outweigh our similarities. All we really do agree on is our right to love each other. Politically we agree on the legal protection of gay rights, socially, politically, medically, culturally. Competing political agendas which go beyond this narrow approach tend to divide us and should be jettisoned as exclusionary of a true, broadly constituted gay community. AIDS is essentially a health issue which neither the Congress nor President can solve. The nineties may be essentially a journey into the soul of the gay community, and there'll be a lot of noise as we separate the men from the boys.

DYR: Gay community and gay identity are political necessities in an intolerant society but if we reach our goal of absolute tolerance those [ideals] dissolve. What I found in very remote places like Alaska was an enormous tolerance of same sex affection, where homosexuality was not perceived as something to be reviled. By the same token there was less gay community among Alaskans because if you're not reviled you can associate with all sorts of people who may not share your sexual needs.

RG: but who share a whole lot more.

DYR: 'Gay' is not a stopping point for people. Gay identity is merely a way station for people as they travel toward 'home.' You're 'home' when no one thinks any differently of you just because you're gay and you don't necessarily associate with other people just because they are gay.

RG: Eureka! Or should that be, 'Amen!'