© 1988 Rich Grzesiak, all rights reserved.

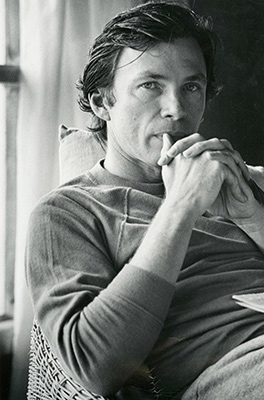

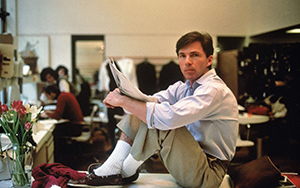

He had pots of money, several gorgeous lovers, innumerable friends whose social connections embodied the "best and the brightest," and entrée into the worlds of fashion, art, beauty—everything we call haute couture. The handsome demimondaine of whom I write is the late Perry Edwin Ellis, fashion designer extraordinaire, who in his prime was hailed as one of the top five artists influencing men's and women's apparel around the world.

At the height of his fame, Ellis' appearance at a local department store would be a local media event. His many society clients included everyone from First Lady Nancy Reagan on down. In the words of his biographer, Jonathan Moor [Perry Ellis: A Biography; Saint Martin's Press, $17.95/hardcover], "How could a man with no formal training as a fashion designer, someone who couldn't even sketch, much less draw a technical design—details that were left to his design team—achieve the summit of one of the most powerful industries in America, creating a fashion empire with retail sales of nearly three-quarters of a billion dollars a year worldwide in just ten short years?"

Even so, at the youthful age of 46, he was gone, debilitated and quite dead of AIDS, but only after having watched his third lover slowly succumb to the same devastating disease.

It's a familiar story these days in gay circles, a fairy tale if ever there was one, except that there are no happy endings save the beginnings.

Let's take the Ellis story from the top: born to upper middle class parents near Richmond, Virginia on March 3, 1940, Perry Ellis pursued an average scholastic career, eventually earning a degree from the College of William and Mary. After some active duty with the Coast Guard, he took a job as—if you can believe it—an assistant buyer of budget dresses. After several promotions and transfers to various clothiers, he moved to Manhattan in the seventies and embarked on a slow but steady rise to the very top of the fashion world. By the time of his death, this preppy Southerner had accumulated an estate exceeding seven million dollars and turned the apparel industry upside down with his radical contributions to the international fashion scene.

But in life, Ellis was a legend to the fashion buying public in a manner that would make any queen jealous. At the peak of his celebrity, for example, Perry made a promotional appearance at Bloomingdale's Fifty Ninth Street Manhattan location that was so flooded with onlookers that even the security guards began to panic.

Yet by the end of his all too short existence, Ellis was infected with AIDS, and rumors regarding his illness sent a shock wave through the normally staid [but homophobic] fashion industry. Even today, his closest associates and friends, including executives at the firm he founded, Perry Ellis International, refuse to confirm or deny that Perry Ellis, kingpin of the dress for success set, died from AIDS.

What was Perry Ellis really like? Why was and is there even today this huge cover-up regarding his death from AIDS? Was Perry Ellis a fraud with no real skill save that of a manipulator who elevated himself to the role of dictator of style? Why is the fashion world, the fourth largest industry in the United States, a commerce with probably the highest concentration of homosexuals this side of the film industry, so reluctant to support anything associated with a gay rights agenda—let alone the costly battle against AIDS?

These questions inspired me to track down Ellis' biographer, Jonathan Moor. A Briton with a dry, if not civilized presence, Moor strayed into journalism only after achieving a successful career as a fashion photographer. He's contributed to some of the top magazines in the U.S., including Vogue and GQ; his last professional affiliation was with Fairchild Publications, producers of periodicals like Women's Wear Daily, W and M magazines.

First and foremost, Perry Ellis was very much a labor love for Moor. He was approached by editors at Saint Martin's Press to tell this intriguing story, one which took over a year to compose and ultimately impacted on his very own career: by the time Perry Ellis appeared on bookstore shelves late last summer, Moor found himself an unemployable commodity in the fashion press, because his forthright book dared to delve into the two taboos of this style crazy world: homosexuality and AIDS. He told me that "I'm actually facing a cruel dilemma right now. I've made my living for many years as an editor in the fashion press, and now I doubt that I can even find a job. I've been tarred by my aggressive pursuit of this project."

Knowing these risks, what was it about Perry Ellis' life that made Moor want to write his biography? "it was a very difficult book to write because from the moment that word got out that I was going to be pursuing this project, the fashion industry almost as a whole closed ranks. No one wanted to talk to me. I even went to dinner with one of Perry's very closest associates who told me what a wonderful idea it was that I was taking on this project. But from that moment on, he not only did not talk to me but did not return my calls."

Moor makes no bones about the fact that "there were some people I contacted at least a hundred times and they would not even bother to return my call. One particular individual—someone I had worked with professionally for the longest time and knew quite well—even answered the phone and denied that they were themselves!"

"No, the fashion industry is very closed on the subject of Perry Ellis, and particularly the very tragic end to his life. They don't want to talk about it, and many certainly don't want to talk to me."

So why is there this cover-up in the fashion industry about AIDS and homosexuality? Certainly everyone knows just how many homosexuals dominate the management of this industry, so I must ask: what is the big deal? Is the fear one that somehow if they find out you have AIDS they won't buy your clothing any more? Is it anxiety that they will actually get the disease?

Moor takes my outburst of a question very much in stride. Like an English headmaster explaining things to a particularly truculent pupil, he acknowledges that "fashion—and the world of clothing—is a very, very personal thing. Certainly what you wear on your body is one of the most personal statements you could ever make. Consider then the gentleman or lady who buys a pair of jeans bearing a waist band with the name of, say, Calvin Klein or Perry Ellis. What do you think that person would do if they somehow discovered that that particular designer was homosexual or that he/she had AIDS?"

"When Perry Ellis died, and the rumors surrounding the nature of his death were so intense, the sales of his fashion wear actually did drop off, if only temporarily."

"So that's the fear. There is this incredible conspiracy in the fashion industry to say or do nothing that would disclose to the general public that one is homosexual let alone that one has AIDS. And yet one must remember that the fashion world has been one of the hardest hit by AIDS and it's being hit harder by deaths from this tragic disease every day."

Isn't this really a ludicrous attitude when you consider it? I mean, by analogy, should we stop watching the films of Rock Hudson just because he died of AIDS?

"Well, as I said earlier, fashion is such an intensely personal thing," Moor declares in his most introspective, highly individual, veddy British way. "What we put on our bodies is one of the most personal decisions we could make, isn't it? And you have to remember what drives this fear: we're talking about the fourth largest industry in the country here, one numbering in the billion upon billions of dollars in the United States, let alone the world. So there's a lot at stake. When you realize just how much money we're talking about, you begin to understand."

But as I was saying, this is all so ridiculous, Jonathan! Claims Moor, "Well, the fashion world is probably one of the most closeted places one can work, even for a homosexual, at least as far as the public is concerned. The world of fashion is a place that prides itself on the sensual, ethereal, professional, almost otherworldly dimensions to its operations, and asking people who own, work in, or manage it to, as they say, 'get real,' is asking a great deal, indeed."

Rumors about the demigods who run the fashion industry abound throughout Ye Olde Gay Grapevine, American Queen Network Chapter. There's the well known European designer who has what they call extreme sexual tastes—something rough to balance all those silky scarves that so punctuate his work. Then there's the American [male] fashionist who loves to limo home to his Connecticut chalet—and deck himself out in the very best women's clothes—a proverbial clothes horse who could easily qualify as best dressed drag queen in the home of the free and the brave. And of course, we can't forget to mention what's-his-name, whose recent and well-publicized marriage to a woman was nothing less than a massive publicity exercise designed to forever camouflage his homosexuality! In 1988, no less!

Moor refuses to comment about these world famous closet queens, and can one blame him? For the "fashion industry," as it loves to bill itself, is a crazy, crazy place, where even one's politics are judged by the cut of one's cloth. Witness the comments of Bostonian David Josef who last July accused Nancy Reagan of approaching fashion from "an ego point of view," adding that she wears "unapproachable" dresses. By contrast, he claimed that Kitty Dukakis projected a "commanding softness" with her "very easy, very terrific [size 8] figure" and "she fosters a look that's something women can really relate to. She's not spending thousands of dollars."

It's obvious from talking to him, however, that of all the big fashion designing queens, Ellis enthralls and mesmerizes Moor. I find myself wondering about Ellis, this "lazy," "introverted, solitary romantic," a "kind, talented and gentle man" who nevertheless "was an intellectual snob [who] did not suffer fools gladly," a homosexual whose lifestyle was an open secret in the fashion business, but who never really donated, until disease was crippling him at the very end of his life, much time or any of his fortune, to gay or AIDS organizations.

The word romance immediately comes to mind when one thinks of Ellis, the very same quality that one remembers about Coco Chanel, a top-drawer, topnotch characteristic rare in human beings and rarer in American business. Ellis' life exudes an operatic flavor a Broadway composer could revel in (I can hear it now, the top disco hit of 1995: "Don't Cry for Me, Perry Ellis"). With this book, Moor has given us a classy, literate look at a deeply private man who was at the very center of an even more private and homosexual world.

If there's a tragic denouement to Perry Ellis, it's a familiar one to people who've seen how one dies from AIDS: the slow, painful demise of a most handsome man, preceded by the equally slow, wrenching death of his lover, Laughlin McClatchy Barker, Jr., also from the dread disease.

1984 through 1986 constituted a period when Perry Ellis International, Inc. went berserk. Its guiding light, Ellis, was frequently absent, caring for a partner, Laughlin, who, like so many members of a successful couple, was also heavily involved in his spouse's business. The sections of Perry Ellis dealing with this tragic time read like outtakes from some lamentable Hollywood melodrama. There's even a photo in the center of the book taken by the world famous paparazzi, Ron Galella: Ellis' body is described as "devastated by AIDS [attending] the January, 1986 Council of Fashion Designer's of America awards dinner, just two weeks after his lover's death."

Moor writes that "it was Laughlin's love, friendship, advice and business acumen that propelled Perry from his position as one of America's foremost sportswear designers into the elite class of world-class designers. Barker was the catalyst, expanding Perry's vision and giving him the confidence to create a design statement that transcended national taste and made him one of those few designers whose influence is international."

Yet all that vision, strength and hope couldn't keep this magical, millionaire couple from being dragged down by one of the most insidious epidemics of the century. Their slow, painful illnesses almost sank their business into disarray, and ultimately, like popular entertainer Liberace after them, forced both into the limelight not only over their dread AIDS, but their sexual orientation as well.

Of course, there remains a Perry Ellis fashion line today, but it's a lusterless collection minus the pizzazz of its master's creations. On November 28, 1988 a new designer by the name of Marc Jacobs assumed responsibility for the Perry Ellis women's collection from Patricia Pastor, who became chief designer after Perry Ellis' death. According to the New York Times, "Retailers said sales have been slipping since Mr. Ellis' death because of lackluster collections."

As I write this, I find myself wondering about all that sadness and glitz and success and pain, about death and life and opulence and joy, and the inevitable gloom that death exacts from all of us, even the well-to-do, immensely stylish, incredibly handsome plutocrats of one of the most influential businesses in the world.

Editor's Note: Perry Ellis died on Friday, May 30, 1986, willing most of his estate to his family and friends. He allegedly is survived by a daughter, artificially inseminated while he was still alive. His last recorded words before he lapsed into a coma were, "Never enough!"