© 1987 Rich Grzesiak, all rights reserved.

If I could pick one year in the 1980's when it seemed like hell had visited earth, I'd have to pick 1987: that was the year Randy Shilts' And the Band Played On hit the book shelves, and death seemed everywhere one turned. The people one knew who weren't gravely ill were heavily sedated, or both. There were people at that time who were painting a dark and very foreboding future for gay men in the post-Reaganoid age.

I wrote for Mark Thompson and the Advocate (among many other periodicals) for most of the 1980's: Mark was a marvelous, gifted, meticulous and altogether fabulous editor who allowed me to interview everyone from Gore Vidal to lesbian activist Karla Jay to San Francisco novelist Dan Curzon. I didn't realize it then, but the journalism I created was helping to record the history of our subculture, be it political, literary, or sexual.

So when Mark Thompson's book Gay Spirit was published, it seemed natural to turn to this remarkable gay man, this quintessential Californian, almost as a prognosticator — a prophet of what to expect in years to come.

The questions he and his contributors posed in Gay Spirit continue to be relevant: What type of culture are we creating as gay men in the United States? What of the deeper ills and issues which seemed to wrack the gay spirit: how did one make sense of them? What special gifts do gay men possess which ultimately yield deeper, searing virtues for our community?

The questions Thompson asked then are just as relevant to us in this latter day age of protease inhibitor AIDS and crystal meth flavored West Hollywood. And the goal he argued for by the year 2000 ["(find a spot) where we can go and nourish ourselves, have a safe place in which to dip down into the wells of our own psyche… and then return to the world…" ] seems as valid now as it did in 1987.

For me, that safe place is Silver Lake, where a brave community of gay men are reinvigorating one of the sturdiest, toughest, most muscular and gentle of gay communities in these United States, a place where gay spirit is no myth, but bears real, deep meaning:

This story shall the good man teach his son;

And Crispin Crispian shall ne'er go by,

From this day to the ending of the world,

But we in it shall remember

We few, we happy few, we band of brothers;

For he to-day that sheds his blood with me

Shall be my brother; be he ne'er so vile,

This day shall gentle condition

And gentlemen in England now a-bed

Shall think themselves accursed they were not here,

And hold their manhoods cheap whiles any speaks

That fought with us upon Saint Crispin's day.

Henry V

This feature was originally published in the October 12, 1987 issue of the weekly Philadelphia newsmagazine, Au Courant.

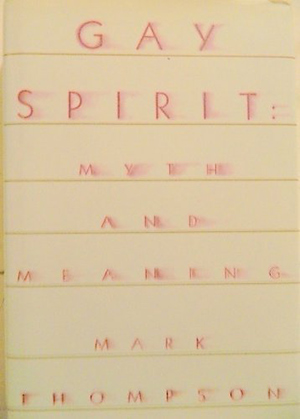

Gay Spirit: Myth and Meaning

An interview with former Advocate editor Mark Thompson, by Rich Grzesiak

Dateline: Gay America, 1987. Thousands of people with AIDS, virulent addictions to sex, drugs, alcohol (addiction treatment counselors reliably claim that more than 30% of the gay community suffers from destructive substance abuse); a political leadership weak and divided, often with no visible support from the community, and a political agenda obsessed with angry confrontations...

The dimensions of the moral and spiritual malaise afflicting gay men in the United States cannot be overemphasized. Far too often, our ideologues have either swept these problems under the rug in the name of gay liberation, or they have rationalized their cause and effect, blaming these ills solely on the homophobic society engulfing us.

Where are we going? What do we believe in? How do we nurture healthy souls as we address terrifying issues of life and death? Are gays just like everyone else except for what we do in bed, or do we indeed enjoy special qualities that set us apart from other groups? Is there a spiritual emptiness to gay life which, frankly, threatens our lives in a way that both AIDS and addiction do not?

Former Advocate editor Mark Thompson, responsible for shaping one of the most successful and powerful publications in gay North America, in 1987 edited a disturbing volume entitled Gay Spirit: Myth and Meaning (originally released by Saint Martin's Press in hardcover, $18.95) in which he and his contributors passionately argued that our identity roots back to subtle, spiritual differences.

We raised these themes in a vigorous discussion: why gays are "different" from other people; how our views of gay identity suffocate any real growth; why culture remains a potent tool to invigorate us; the responsibilities of the gay press; and more.

Here's how it went:

Rich Grzesiak (RG): If a wise person is someone who asks the right questions but does not necessarily supply the right answers, then you echo that notion in your introductory comments. So I want to put you to the test, if you will: What do you mean by that anomalous phrase "the gay spirit"? Could you expand on that concept for readers?

Mark Thompson (MT): I think that gay spirituality is something that hasn't been explored to its full depth or capacity yet. I think what it encompasses is a different way of seeing and perceiving the world — in other words, reality and what we manifest from that reality. Now, perhaps that isn't saying a lot, but I think that if we can stop and expand on that in our own ways and really take time to consider what that might mean for us, I think that the vision and results produced can be very, very important not only for our own lives but for the lives of others.

This goes back to one of the central messages of Gay Spirit. Why are there gay people, or, as I prefer to phrase it in the book, why are there the type of people that we now call gay? Gay identity, as we currently know it, has been socially constructed, although I do believe that the type of people that we now call gay have existed on the planet for a long, long, time, that this represents a variation within the species with subtle but important lessons for all of humankind.

RG: This "gay spirit" or "gay vision" that you refer to — it's been years since the Stonewall revolution (1969). There are gay institutions and gay politicians and gay leaders and gay activists who regularly receive testimonials and accolades in the page of our press and from dioceses and podiums around the country. Isn't their good work enough to give us the "gay spirit" or even "vision" that you recommend so highly? What is wrong there?

MT: I don't date the gay community just back to Stonewall. Gay identity as we currently understand it was formulated in the late 19th century. I think, therefore, that it's important to understand that our modern movement began about 100 years ago, gained a lot of strength and impetus during World War II and the years that immediately followed and then, of course, bubbled out [sic] in the young activists' generation of the 1960's, which you and I belong to. I really do view gay history as all of a piece.

Now there's nothing wrong with the institutions we've built up to this time. I just think that there's now a ceiling on gay identity. In other words, the way that we are now viewing it is a limited thing. There's no other place to go with it. It's become a very isolated thing. Look at a community like San Francisco — where I'm from and treasure very much — yet I feel the community there is so self-reflected and insular.

You see, we always need to be rejuvenating the language of self, and I think that's something that the community as a whole hasn't done. It hasn't looked closely enough at what the very concept of being a homosexual in this culture is. Much of the gay movement has been posited on the belief that gay people are just like everybody else except for what they do in bed. What Gay spirit is really saying (is) let's just turn that upside down or inside out, and say that our sexuality is very much the same but it's our perspective that's different. We need to always be in a state of questioning ourselves, our identities and our values.

Inward looking is where we need to go now [1987]. It's the direction we're obviously being called to with AIDS.

RG: I suppose it's emblematic of my own East Coast bias that when I ask (you) questions about why gay spirit is lacking, I tend to think in terms of institutions and human beings and want to fix the blame on them, whereas, if I'm hearing you correctly, you're saying that we need to turn inward spiritually and psychologically in order to find this gay spirit.

MT: We need to rejuvenate the very meaning of what the word "gay" is both politically and socially — and primarily for ourselves. We need to come to some new, depthful understanding of it. It's not enough to just say that we're like everybody else. I don't believe that. I truly do believe that we're different.

Now by saying "different," I don't mean "better" or "superior," I mean different in terms of social roles and social purpose, rather than just sexual identity. This is a very crucial and subtle point that I'm making.

RG: As you know, people would beg to differ with that belief… they would maintain that gays are indeed just like everyone else and that, in fact, your definition of "different" is just a rationalization that is used to put parameters on our politics, for example.

MT: Again, by what I'm saying I'm not negating anything that's been accomplished up to this point. By saying what I've been saying, I'm trying to add on a new layer of meaning and provide new directions. It's obvious that our community is always going to be under attack from somebody, whether that be religious fundamentalists or political hacks. But in order to survive — and what's more, to truly flourish — we need to have a more insightful knowing of ourselves. That why's I end Gay Spirit talking about the radical faeries and rural gay men who have gotten together in isolated spots and begun to explore the dynamics of their lives in ways that are authentic to them.

You see, if you're just surrounded by heterosexual role models — and we are, in a sense, aping those — that just doesn't really tell us too much about where we might really be coming from. We could be throwing something very valuable away without really knowing what it is that we have.

RG: In one of the introductory sections of Gay Spirit, you write that "gay male consciousness remains stymied, unable to come of age." So much gay-identified culture appears to lack "deeper meaning," which expresses these same sentiments differently. I see so much malaise and pessimism in our midst — not just cynicism anymore, but a moroseness that affects not only our view of gay culture, but gay politics, gay anything. I'm using gay in the broad sense of your meaning and not just as a prefix.

MT: Well, you know, depression often comes from people being in a stuck place. I'm not just talking about the depression that we are all feeling these days [1987] due to the health crisis… I'm talking about depression that comes from a deeper place. We have been systematically cut off from the watersheds, from the very deep wells from which our spirits come. Of course, this is something that our society, particularly American society, does: it constructs the means to cut people off from themselves, so it's easier to control them.

One of the things that they've attempted to do, you see, is construct this inauthentic, artificially constructed bell jar, this "myth of the homosexual," and we've been put under it. We just haven't really been able to take the time, given that we've been so busy defending ourselves and surviving, to see what lies deeper, what our intuition and our dreams are saying to us.

The West Coast has always been a very fertile breeding ground for new ideas… there's many social and natural elements that have formed a less-inhibiting regional character out here, which I think makes many of us more open to personal seeking or inner questing. Here many gay people have risen to that opportunity and explored. There's a real need to transmit these messages out into the rest of gay culture. Many contributors to Gay Spirit basically come from a West Coast experience… writers like Mitch Walker, Harry Hay, Aaron Shurin, James Broughton, Judy Grahn and Arthur Evans have influenced my experience as a gay man. I wanted to collect all of this together between two covers and share that with other gay men. Gay Spirit represents a very important body of opinion that has not been in the mainstream of gay writing or the gay press.

RG: If we could take the perspective of the gay press or gay periodicals, it seems that they are Balkanized now [1987], and even calcified in certain areas. Certain gay publications seem to have stylized style, with no substance underlying it at all. I pick up on comments in your preface that our literature seems to have gone beyond meaning and become flashy with no depth.

MT: I don't know — I think there's some very wonderful new gay writers out there that are busy with this rejuvenation of self, but they are relatively far between. But I do think we are right on the edge of a new wave in terms of gay literature. The message of Gay Spirit is something that's going to be accepted and intuitively understood by many gay men now, where even five years ago they wouldn't be so open to the messages of the book. Gay identity has shattered somewhat and we need now to look at the void.

We need to always invent ourselves — we need to find the courage to pursue that journey. It's basically an inner journey that we can take alone or together in small groups, but something that we can also nourish and support in our public forums. It's a very crucial journey.

Gay Spirit is basically designed for gay men because I think that many lesbians and feminist women have taken this journey together during the past decade or so. Gay men haven't. We've been very privileged and self-assured. Now, of course, that has been shattered by the utter horror of AIDS. We're golden boys, who are now looking at our deaths. Many of us are now questioning ourselves and looking inward as never before. We need help for that, and that's why Gay Spirit was produced.

RG: There's an implication or subtext to many of the entries that almost want to cry out and say that there's a new millennia on the way, that this diseased, war ridden planet of ours is about to give way to some new golden light that is going to lift us up from this inward-looking phase we are about to enter into.

MT: Well, I think there is a new eon or a new age coming. I don't want to sound overly obscure or mystical, but out of the rubble of the old, as we go from a modern, industrial society to a post-modern, post-industrial society with all that that means — our global village has shrunk, just as McLuhan said it would — many of us are beginning to see the interconnectedness of all living things on the planet. Indeed, many of us are now beginning to see that the planet itself is a living organism with its own particular form of bio-consciousness. The very important role that gay people have to play in this burgeoning consciousness is demonstrated through the certain social roles that we enact, indeed, by the work that we seem to do best. Gay people seem to excel in the areas of teaching, healing, compassion, empathy — our vision can see two opposing things at the same time and unite them into one new expression or idea. If you look at gay art or gn, or even something as ephemeral as fashion itself, you will see these elements at work. The gay psyche goes beyond a male/female dualism. We come out of a different place. Certainly we are biological men dealing with men's issues, but in terms of deeper soul business we are coming from some other place, a "neither place" in the words of Harry Hay.

RG: I was glad that you included an excerpt from Geoff Mains' Urban Aboriginals. I notice that certain reviewers, particularly Publishers Weekly's, have gone right for that. Leathermen are a subculture unto themselves, almost like an Indian tribe. There's a wonderful line in your intro to Mains' section that "leathermen are a fellowship without a church."

MT: Yes, I believe that very much. I have participated in leather culture myself. I would not say that I am a "leatherman" or a member of the leather community, but I have had some powerful experiences with that. Politically, I would extend that solidarity to that community, which I think has been horribly misunderstood… by their brothers and sisters.

RG: Leathersex is often perceived as a pathology or seen as riddled with substance abuse as well as other destructive practices…

MT: Just as cross-dressed people in our community have always been referred to as "dizzy queens" or losers. Yet time and again you see these people as helping to move things along and mediate community concerns… They perform very much a shaman-like role. In any good leather scene, you often see one man leading another to a very profound, deep, or at times dark and unresolved place where new insights and catharsis are achieved — a shamanic role, to be sure.

RG: Moving along: you've spent a major portion of your professional life now — 12 years — working in the gay press as Cultural Editor at the Advocate. In a very general way, based on that experience, how would you describe the state of the gay press these days (1987)? Are there changes you would like to see?

MT: I think that it's wonderful that we have so much gay media. Every medium-sized town in gay America today seems to have a gay paper...

RG: Quantity is always lovely. But what about the quality?

MT: Well, one of my concerns here is working with writers, and I'm so tired of hearing stories about the publishers of these papers abusing their gay writers and contributors. This must stop: it really dishonors the people who personally extend themselves to report and to write. There is real abuse there and that is a primary concern I have as an editor — we need to find some way to address that and when we do, we are going to find a better quality… (Due to poor treatment of our writers) I see that we are losing some of our very best people. Certainly, one of the major problems our community has got to face is low self-esteem and the internalization of the stigma of society's hate we all have to bear. We can't continue to inflict that on each other. It's so important to always keep our consciousness raised around this issue.

RG: A common criticism one hears about the gay press is that it is too political (1987), that it does not reach out to the needs of its apolitical readers.

MT: Remember: really deep changes come through cultural channels. I think that we need to do whatever we can to support our artists and our writers. I'm not interested necessarily in building an autonomous gay culture or a society that would just stand unto itself. I think we need to have that to develop our own ideas for our own lives, our own selves. I just don't think that buying votes from the Democratic Party is in any way the full sum of what the underlying strength and potential of our community is.

I put a very high emphasis on books at the Advocate… because books are the very foundation blocks of our culture — they will endure. I would like to see the gay press do more to cover writers and issues and ideas rather than just reporting on events.

RG: If we could look forward into the year 2000, when this millennia of our gay spirit dawns, what kind of changes do you see for us as a community?

MT: That's so hard to say at this point (1987) because there's no telling where the AIDS crisis is going to go… yet this, too, will pass, and most of us will live to tell of it. I expect to be among those still standing and to still be doing my work.

What I would like to see is the development of more gay retreat areas in isolated places around the country established as self-sustaining, rural communities. We are going to need them. It's important to have our own land.

I'm not saying that we should all just go off into the country toward some utopian dream; I refer to places where we can go and nourish ourselves, have a safe place in which to dip down into the wells of our own psyche… and then return to the world… I want to do everything I can to promote that.