© 1987, 1988 Rich Grzesiak, all rights reserved.

Meet Leonard Bernstein.

Darling of cafe society. Conductor laureate of the New York Philharmonic and the Israeli Philharmonic. Composer of great Broadway musicals (like West Side Story and Candide). Esteemed lecturer at Harvard. Recipient of a gold medal from Deutsche Grammophon, one of the world's leading record companies. Benefactor of the state of Israel since its birth.

Champion of liberal causes since the 30's and a staunch political ally of everyone from J.F.K. on down. The world's leading interpreter of the symphonies of Gustav Mahler and the conductor preferred by the late Dmitri Shostakovich. Loving friend of such (classical) musical luminaries as Aaron Copland, Serge Koussevitzky, Marc Blitzstein and others.

From the cognoscenti of the fine arts to the heathens of the middlebrow, he is regarded as a titan, a genius, the doyen of all that a civilized society prizes.

Or is he? Was his achievement gained at a great price that renders his many honors meaningless? Was his marriage to the late Chilean actress Felicia Montealegre a fraud designed to further his ambition and forever confuse those who would accept unquestioningly his heterosexual facade? Did he "borrow" some of his greatest melodies (like "Tonight" and "Maria" from West Side Story) from other composers? (there's some strong evidence to suggest he just may have). Why has he been so consistently unkind to women (like the late diva Maria Callas)? Does he mix art and sex interchangeably?

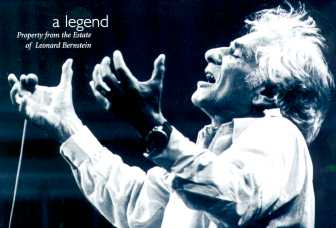

Bernstein is a tortured "errant god" who embraced the old Stokowskian role of iconoclastic educator and joined it to the frenetic style of a Mick Jagger.

Joan Peyser (pronounced pie-sir) has chronicled this "Frank Sinatra of conductors," compassionately evoking what she claims is "his" story. She talked to literally hundreds of sources and sifted through all the anecdotes hitherto thought apocryphal: the Philadelphia night when his antics caused the chandelier in the apartment below to crash; the orgy he attended in Rome organized by Gore Vidal; the Hollywood evening he received visitors in his dressing room clad only in a jockstrap; the time he publicly and drunkenly humiliated the conductor of his Mass; the day he fired the entire recording crew at a D.G.G. studio session; the Dionysian appetite for homosexuality that infuriated his late wife and scandalized what is left of "society"; the luncheon when the late Chicago Symphony conductor Fritz Reiner told him that he was a sh*t; the stories go on and on and on.

Bernstein celebrates his seventieth birthday on August 25. In her recently reissued Bernstein: A Biography [Ballantine; $5.95/paperback], Peyser attempts to tell us just what kind of man this septuagenarian is, why he has been so dogged by frustration and failure in his later years and why has he done what he has—to the amazement of the world.

I caught up with her by phone and here's how it went:

Rich Grzesiak (RG): Over the years I've heard many stories through the gay grapevine alluding to Leonard Bernstein's difficult, prima donna like qualities. Why would you want to devote so much time researching the life of such a seemingly difficult person?

Joan Peyser (JP): Because Bernstein has done something that no other American has done: he was the first American musician to become the music director of a major symphony orchestra in this country. He is the first creative performer to gain international renown as an American.

I don't believe that a man is separate from the world around him. The world affects him, then he makes art which changes the world a little bit and then that new world affects him yet again. The context in which Bernstein has moved illuminates not only a man who is central to our musical life but life itself.

RG: To what extent did Bernstein cooperate with your research?

JP: He was as cooperative as I could have wished him to be without my having to pay the ultimate price, namely, to submit the manuscript to him I've been writing on composers for more than 20 years and I have never submitted a piece to the subject for approval or correction.

When Bernstein premiered his opera A Quiet Place (1983), he did very little to disguise the characters, which are quite autobiographical. The reaction of the critics then is not unlike their response today to my book, that it is all so ugly: how can a man with such enormous talent spend his life dealing with such dreadful, ugly people and without any understanding that these people were himself, his parents, sister and life? They couldn't get past the libretto to hear some of the complicated, beautiful music in that opera.

RG: You refer to some ugly areas that affect Bernstein's behavior toward both himself and other people. Have you spoken to him since your book was published, if only to get his reaction to these stories?

JP: Not directly, nor did I expect to even in those past cases where he authorized books about himself or maintained some degree of control, he acknowledged neither authors nor their work.

I have heard indirectly from close friends that he is pleased [in] that he feels that it's finally his story Bernstein wants to be respected and loved for what he is, not for some false representation. Yet everyone around him still feeds on a nineteenth century European image of the artist/musician as a spiritual leader/priest

RG: There are, however, some cynics who would say that since you have washed all of the dirty linen of Leonard Bernstein.

JP: I haven't, believe me! You cannot imagine what I censored out.

RG: I hope to get to that. Since you have laundered some of Mr. Bernstein's dirty linen in public there is now no obligation on his part to talk about his life or even to deal with the more sensational aspects of his personal behavior. He can simply move on, leaving the controversy you've raised totally forgotten. Will he ever write his own autobiography?

JP: In 1986, when the New York Times Magazine profiled him, Bernstein said that after my book came out he intended to ask his friends to help him reconstruct his life. Using a video recorder, he would tell his side of the story and all would be revealed after his death.

I must say, however, that I have told his side of the story and people close to him feel it's a compassionate portrait so I'm not sure he'll still do it.

But there are special dimensions to my book: one is that I had access to Bernstein's relatives and associates regarding his formative years and two, I'm writing about someone who's [still] living. That really is the honorable thing to do because then he's able to respond to what I've set down.

[It's remarkable that] with all the brouhaha that this book has unleashed, not one substantive fact about Bernstein's personal life cited in it has been challenged. People may claim that I referred to the wrong scene in Medea, but nothing about the man himself has been challenged.

RG: The New York Native (a defunct gay Manhattan weekly) accused you of factual inaccuracies. When you describe Bernstein's sexual promiscuity, its critic asked, how were you, Joan Peyser, able to corroborate those allegations let alone the gender of Bernstein's conquests?

JP: I didn't attribute certain details to people because I did not want to destroy their careers or lives, but I can tell you that in general, even in a very specific situation, I never would print a story unless I absolutely had two distinct sources that could not have had a common source. In terms of Bernstein's promiscuity, there were not two but dozens and dozens of people because Bernstein is not secretive. In fact, when the book first came out a New York Newsday reporter called composers Morton Gould, William Schuman, Lukas Foss, and others. All of them told Newsday that, as far as the sexuality goes, nothing is new here, as Lenny has never been secretive about himself or his preferences all his life everyone in the musical world knows these things.

The San Francisco Chronicle claimed that "for many informed observers of the musical scene, their problem with Peyser's searching study is that it is penetrating and true and they know it. Much about Bernstein that will surprise general readers has been commonly known in the musical community as long as he has been around. It's been so well known and so publicly displayed by the man himself that musical people take his history and complete personality, flaws and all, for granted. That's Lenny."

If anything I've disclosed about Bernstein's rapacious sexual appetite is wrong, I ought to know as the book has been out for a long time. If one starts to leave out pieces of the intricate puzzle of an artist's life because something is indecorous, you don't get the complete picture.

RG: If Bernstein were in the room right now and the two of us were to turn to him in unison and ask, "Many people have come out of the closet and indicated that they're homosexual are you homosexual?", what would he say?

JP: Well, in London two years ago someone did do just that and Bernstein walked out of the room. The New York Post ran a piece where the reporter managed to semi-suggest it and even got Bernstein to discuss his late wife's reaction.

RG: With the death of Bernstein's wife, Felicia Montealegre, the days of his heterosexual facade seem to have faded once and for all.

JP: Well, even before her death

RG: In your book you quote Bernstein to the effect that he has been heterosexual and homosexual, but never both at the same time. That doesn't really deal with The Issue at all.

JP: It deals with it as accurately as he could. He spent many years as a homosexual and then started a family and for a number of years was a devoted heterosexual, at least in New York. People have described [to me] incidents involving him abroad but the basic thrust of his life was as a family man for a number of years and then he reverted back to homosexuality. So I don't think his comments are so absolutely off-the-wall at all.

RG: You also quote from a racy 1962 UPI dispatch datelined Woodbine, Georgia. Only the Philadelphia Bulletin and Time Magazine gave it any play.

JP: There was a U.S. Marine Corps deserter Bernstein had then taken into his employ. Something happened and the guy simply left with Bernstein's car [Editor's note: the "car" was a brand new convertible. The deserter was Bernstein's "chauffeur" at the time].

Bernstein was very closed about it. Most people I spoke to were impressed at how fortunate Bernstein was that the press didn't zero in more but concentrated instead on making suggestive, titillating comments. Nothing explicitly defining the situation ever made the papers then.

RG: Was the career of Bernstein's predecessor as conductor of the New York Philharmonic, the late Dmitri Mitropoulos, affected by homophobia? Did Mitropoulos lose his post at the Philharmonic (1950-58) because of his (homo)sexuality, or was that just one cause among many?

JP: I think it was [a factor]. As a conductor, Mitropoulos had a very painful life because he was certainly obliged to be celibate he knew the terrific risk if he strayed from that.

Mitropoulos was monk-like in his study of and devotion to a score, yet he was an exception to the rule that held that a music director of a symphony orchestra had a social responsibility to its trustees and board to present the facade of a respectable family man. Mitropoulos lived a terribly difficult life particularly when in this country.

RG: Are Bernstein's children very accepting of his homosexuality?

JP: Yes, very, and they've lived with it for so long. Halfway through a discussion I had with them I brought it up.

His youngest child (Nina) hadn't been aware I was going to deal with it there was no way not to. Anyone I interviewed had a hard time not talking about these matters.

RG: In his life today, does Bernstein have a Significant Other as far as a relationship is concerned?

JP: No, he does not. I think he really rarely did. There was only one and only for a brief period. Basically, there doesn't exist an intimate, romantic kind of relationship that allows him to live in comfort, peace and harmony with someone else.

RG: One of the most interesting sections of your book examines Times' classical music critic Harold C. Schonberg. [Editor's note: For years, Schonberg attacked Bernstein's career with the New York Philharmonic in the New York Times. Schonberg rarely had a good word about Bernstein and seemed to specialize in rough, nasty accounts.] Did homophobia influence that or was it just a personality clash?

JP: It's interesting that you ask I hadn't considered [homophobia], to tell you the truth. In the book, I portrayed their interaction as belonging to a bloody tradition where the chief critic in New York takes on the music director of the Philharmonic to test his muscles and see how long it takes to destroy him [this hostility] goes all the way back to the 1840's when critic Henry Cood Watson battered away at Ureli Corelli Hill, the Philharmonic's first conductor.

More likely, it's Schonberg's envy in that he's such a controlled personality while Bernstein is comparatively free, celebrated, musical and successful

RG: How do you respond to critics who claim that your book is cheap pop psychobiography? A hostile reader might complain that, in order to appreciate his music, one doesn't need to know that Bernstein once attended an orgy that Gore Vidal organized in Rome.

JP: Leon Edel [author of a mammoth, five volume biography of novelist Henry James] once told me, "My dear, all my career I have been accused of psychologizing too much, excessive Freudianism, psychobiography. I laugh. It's because of the particular prism that I have (and you share with me), that I have succeeded where everyone else has failed. The James family told Edel that he is absolutely on target; the people close to Bernstein who have read the book say precisely the same thing to me. There is not a nuance that is off base.

RG: On the surface, Bernstein's success would indicate that one can be openly homosexual and quite productive, if not esteemed in the world of the fine arts. But both of us know that there are well known people in the classical music world very deeply in the closet who choose not to be as open as he's been.

JP: I do think that Leonard Bernstein could come out in recent years or even today because his power, personality and musicianship are so unquestioned. I'm not sure that he could have managed it years ago I wouldn't at all say that he could have made a successful career if he had from the start openly acknowledged [his homosexuality] and not made an effort to try to figure out the right ways to move in terms of his career.

RG: If Bernstein were coming of age today, could he make it?

JP: Oh, yes, I think it's possible because after all, today we have many homosexual conductors. It's true that none of them have huge orchestras yet but it's much easier and that's a wonderful thing.

RG: How productive a composer will Bernstein be during his seventies? Have we already seen the best of his work?

JP: We know from history that Verdi produced his two greatest operas at the very end of a very long life. I think that in recent years Bernstein hasn't enjoyed success or collaborated successfully because for the most part he chooses [to work with] very young people who won't give him a fight for his money rather than the enormous artists he had [access to] in the 1950's.

He had been working on a piece with [choreographer/director Jerome] Robbins and [playwright John] Guare, based on a play by Brecht later made into a musical, called The Exception and the Rule. He has had hard times in recent years with composition. Yet I'm certainly not going to be the one to say that he won't surprise us with something remarkable. Of course, I hope he will.

RG: Has Bernstein turned his back on composing for Broadway?

JP: I wouldn't say he ever turned his back on it. Certainly, his musical 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue was a devastating experience. He said then [1976] he would never go back but redirect his energies to compose opera. That's how A Quiet Place emerged.

RG: Father figures like Mitropoulos were an important factor in Bernstein's emotional development. There is no such apparent figure in his life today.

JP: I think that there are tremendous ghosts. If [his father] Sam wasn't such a powerful ghost, Bernstein would not have experienced the trouble of actually coming out and somehow writing the story of his life instead of hiding it under music and wondering if people will get it. There's this ambivalence: he wants it all out and yet there are many pressures that prevent him from saying it, one being societal (all of the organizations in the musical industry) but he's still living with the influence of Sam, his father. People don't just die and lose their power over you.

RG: Are you saying through your book that Bernstein's creative output suffered a severe penalty because of his sexual promiscuity?

JP: No, that's unfair because the major thing I don't do in the book is moralize. I am a biographer. I try to make connections, describe what happens and give possible, even probable causes or motives for actions. I am certainly not one to say, oh, well, if he had continued to be a good husband and father and suppressed all of these drives and redirected them into his art, then he would have gone on happily creating great masterpieces for the rest of his life. I would never claim that because, what if he could have? If he could have, he would have, it's such a reflexive thing.

Things happened and he couldn't I hope that [judgmental] tone is nowhere in my book.

RG: In preparing for this interview, I watched several of Bernstein's recent concert films and was struck by how different his physical appearance is even in the space of one year. In one installment of Bernstein on Brahms he looks quite well, while another displays a dissipated looking quality. Is he in good health?

JP: Everybody asks me this. As far as I know he is. He smokes, he drinks a lot, he's a sleepless person, his face and body look unquestionably ravaged. Unlike many of his contemporaries, he makes no effort to look trim and thin.

I don't believe he could possibly keep up with the intense schedule he has if he were not, finally, in pretty good health.