"Certainly, there's always been a tradition of gay mystics. Just look at Allen Ginsberg. There's something about the gay sensibility that's mystically inclined."

Does that statement startle you? Are you turned off by the discourse of visionaries? Do you believe that humanity can completely comprehend its condition and can use science to penetrate its very soul? Or perhaps you believe there is something more valuable than the scientific rationalism that has dominated 20th-Century thought and, yes, even gay social commentary.

If these questions make you uncomfortable, I recommend you read Hardware Age. But if you have always wondered about the things we cannot explain, you might want to peruse the recent works of Edwin Clark (Toby) Johnson.

Johnson is a gay man of wide interests and a complex style. For several years a member of the Marianist Brothers and later of the Servite Fathers, he studied at the Catholic Theological Union in Chicago and at the Service Priory in Riverside, Calif. In 1970 he left the Servites to continue his education in Northern California. Trained in psychiatric nursing at Napa State Hospital, he received a Ph.D. in counseling and psychotherapy from the California Institute of Integral Studies. His religious beliefs now extend far beyond traditional Western Judeo-Christian thought. In this cynical age, Johnson believes that "God exists in all of us," especially among gays.

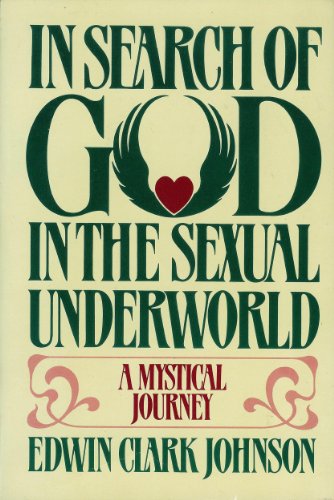

Johnson has written two fascinating books that are as unorthodox as they are profound. In The Myth of the Great Secret, he states the case for "divining the world" by realizing that we are our own heroes. His latest work, In Search of God in the Sexual Underworld (available used from Amazon resellers, but originally published by William Morrow at $13.95), a highly unusual account of his experiences while writing a report on juvenile prostitution, personalizes what Johnson calls the "hero journey." His research emerges with the rich texture one would expect from a self-described "hippie, psychologist, mythologist, scientist and mystic."

Johnson has created a second edition of the book entitled Finding God in the Sexual Underworld: The Journey Expanded — you can find it available on Amazon in Kindle and paperback editions.

Johnson lives and works in San Antonio, Tex., where he is well known as a gay community activist. He was recently in New York, where we talked about a number of issues: sexuality, leadership and gay politics, as well as subjects not normally tackled by gay writers—matters of life and hope, and even God.

Do you agree with John Rechy's assertion that there's no substitute for seeking salvation? How do we go about making our way through a gay world that has debunked most of its life-giving myths?

The issue of finding myths to live by is crucial. Human beings need meaning in their lives.

From one perspective we can look at reality and see there really is a connection between events. Maybe God really is active in the world. Our scientific rationalism suggests that things "just happen," and most of us live in such a way that things just sort of happen to us. So we have to impose meaning on what we see, and we do that by creating myths.

The myths Rechy refers to in his literature appear to have been debunked only when one comes out of a very one-dimensional epistemology in which things are either true or false—in which there is a single reality.

I think there are many realities—scientific, historical, statistical. Those are the ones we tend to think of as true, although if you examine them carefully, they prove to be not as devoid of falsehood as we originally took them to be. People do historical research and discover that we've misunderstood the past all along. An interesting gay example of this is John Boswell's study of the church in medieval history. We all knew that the church was anti-homosexual and Christianity was antigay.

Now along comes Boswell to expose the truth, and suddenly history changes behind us.

As we become more sophisticated in our understanding of reality, we must appreciate what the ancients knew: that there is more than one reality and that we can select the myths we will give meaning to, ones that must have good consequences for our lives.

Christianity has taught us to edit our experience negatively, and all that does is create lots of problems. The ultimate argument of The Myth of the Great Secret is that if we begin to see things more positively, they will eventually begin to get that way.

We still don't understand the historical Christian experience because of linguistic difficulties. The Bible tells us that Peter left his wife co follow Jesus. There's obviously more to that story than what has been recorded in the Gospels.

Just imagine the difficulties inherent to interpreting literal accounts of biblical events over 2,000 years old. Pepsi Cola once had its jingle literally translated into other languages. The ad slogan in English was, "Pepsi brings you to life." Translated into German the jingle meant, "Pepsi brings you back from the grave." In Taiwan the slogan became, "Pepsi brings your ancestors back."

We still don't really understand what Jesus' relationships with the Apostles were. There is a funny euphemism continually used in the Gospel of John, "the disciple whom Jesus loved." Doesn't that mean Jesus's lover?

We know that one of Jesus' closest friends was a prostitute (Mary Magdalene). The Apostles themselves were lowlifes—sailors. Through the filter of 2,000 years of history we've shifted them to the status of middle-class respectability.

A year ago Allen Young made a historic break with the American gay left, in his Gays Under the Cuban Revolution (Grey Fox Press). One of his main points was that when we lock ourselves into a black-and-white world view, we shred each other's integrity—politically and socially—as gay community leaders.

You must remember that gay liberation occurred at a time when many people were very angry at the United States. In the parlance of Toby Marotta's The Politics of Homosexuality, I'm a "cultural radical," someone who wishes to alter the culture by altering the way he lives. But that doesn't necessarily lead one to accept a Marxist analysis. In general the movement has gone far beyond the political/economic issues of the 1960s.

People have often taken the maxim "the personal is political" to mean that their political analysis allows them to target people for personal attack, purely because their opponent's politics are unacceptable. Thus, everything political must equate to everything political.

Everything you do has political implications, but you aren't necessarily supposed to be politically correct—the latter is the distortion. The personal decisions you make must be seen in a social context. How we behave somehow affects the collective mind. We have ethical obligations to behave in right ways toward other people, but the right ways are not as cut-and-dried as political analysis would have it.

The Christian idea that we should love one another is irrefutably true. When we're in a context where this is not the rule—with people crying to get what they want or be politically correct—they wind up shitting on one another.

Perhaps the gay movement has been guilty of "sloganeering," of mistaking political axioms for real political analysis.

I have a great tendency to romanticize early countercultural ideals. I learned to be a hippie when I was in the monastery. Right now we have the controversies surrounding Larry Bush, NGTF [National Gay Task Force], GRNL [Gay Rights National Lobby] and The ADVOCATE-maybe that's part of becoming successful in America, because that's what Americans do to one another.

Whether it's hippiehood or homosexuality, the Roman Catholic Church seems incapable of dealing with either. Do you think the church hierarchy will ever deal with its aversion to homosexuality?

Recently I learned that Pope John Paul II had asked for a copy of The AIDS Epidemic [Saint Martin's Press]. Still, if the church makes declarations against gays, all it accomplishes is the alienation of homosexuals. There's no need for them to do that. If they come out with a positive statement on gays, they alienate all the homophobes.

Historically, the only choice left to the church on gays may be silence, which is what happened with birth control. After much raging controversy it just stopped being talked about.

We've created many self-defeating myths to get us through gay life: the doomed queen, the sex-obsessed stud, life in the fast lane, to name just a few. But we're finding that none of the myths are working to give life positive meaning in the AIDS era. As these myths die, do you see an upsurge of interest in spirituality among gays?

I hope so, for salvation is the issue. That doesn't mean heaven but the full life—loving relationships, living well. I am not referring to the old Christian eschatology about salvation.

A spiritual approach to life is important because the spirit is as intrinsic to human experience as are our bodies and minds. Omitting spiritual awareness is like neglecting our bodies' needs.

When we create new myths, we should hark back to, and be consistent with, the ancient traditions. A myth like the resurrection has survived for over 50,000 years because there's some thing intrinsically human about it. The myth of the doomed queen means nothing unless we can place it in the hierarchy of historic mythology. If we're going to base our life on myths, let's choose a very basic one, and not the doomed queen.

There's something very true about the myth that drugs can bring you enlightenment. We took LSD to show us heaven. Then we starred doing drugs just to go to the discos, but that's a dead end. The truth about myths, like the one that "drugs are good," is not historical bur experiential.

As a community, how can we create heroes—or heroic myths—when so many of us are busy fighting for survival and at the same time are so terribly ignorant of our gay past? Do we have to reconstruct our past before we can gain a heroic future?

The reason we develop public heroes is to discover the heroes in ourselves. The hero journey permits us to piece together all our experiences and to grow in positive directions.

A more basic myth is that of the great secret, that there's some place to go, something we ought to know but don't: If only we knew this one bit of information, everything else would make sense. Today we're afflicted with a fatalistic notion that we'll never find the secret, so why bother looking? Let's just be satisfied with a new VCR, we tell ourselves. But there's a great human hunger to understand the meaning of life.

There seems to be a tremendous contempt among gay intellectuals for any interest in spirituality, let alone religion. Have you experienced that?

Yes. People think I'm really nutty because of the religious paraphernalia I'm fond of. But in Texas where I am political, people aren't even aware of this part of me.

When people perceive that you're gay and religious, does that pose problems?

Well, we must remember that the great reality of our day is pluralism, that there are many truths. Among the organized religions, the opposition to homosexuality doesn't arise from any injunction in Leviticus but rather from the suggestion that our lives imply that there's more than one reality or truth. Gays disturb their assumptions about the nature of reality, their egocentricity. Remember too that the Romans had no reason to wipe our Christianity; they opposed the Christians because these new-found religionists wanted to wipe out everybody else, such was their belief that their creed was the only truth.

How do you regard organized gay religious groups like the MCC or Dignity?

We go to church to have our religious consciousness raised. To the extent that their liturgy is effective in this respect, I enjoy having my spiritual awareness stimulated.

A flaw in these groups is that they're not sufficiently "gay," in the sense of recognizing that to some degree being "gay' involves being critically aware of society. Gay churches too easily accept traditional Christianity without trying to take a critical distance and reshape the religion.

Every time I refer to the MCC I belong to in San Antonio as "the gay church," someone objects, saying, "We're a Christian church with an outreach to homosexuals." Even Troy Perry subscribes to this descriptive notion. But they're wrong—they are a "gay church."

One of the functions of religion is healing. Maybe that is the main function of gay religious groups these days.

Could you explain that in greater detail?

Maybe there is some truth to the idea that AIDS is a manifestation of sinfulness, Susceptibility to viruses has strong psychological components. Guilt and stress do make one more susceptible to viruses. That's what I mean when l say that perhaps AIDS is a manifestation of sinfulness. To the extent that many gay men have feelings of evil buried deep inside and have no way of reconciling them, these feelings may well bubble up in self-destructive ways.

Compulsive sex is bound to be emotionally unsatisfying. It's interesting that AIDS has appeared when the first generation of the sexual revolution has hit its 30s.

We really aren't free unless we have some kinds of limits on our freedom, and those limits are based on responsible behavior. We've had people who have behaved irresponsibly in the name of gay liberation. Many of us were reluctant to say so because we feared we'd be seen as gay Jerry Falwells.

As far as sexual morality goes, if we talk in terms of what makes people happy—i.e., virtue—then that's a much better way of nurturing behavior than saying, "Here's a list of what's forbidden, now see to it that you don't perform any of the following sexual acts." Christianity has been forbidding things for almost 2,000 years, and it hasn't accomplished anything.

Issues of personal responsibility intrigue me. You've been involved with est and Werner Erhard. Est claims that individuals can and must take responsibility for their lives and turn acts to their personal advantage. What would you say to a gay black or a lesbian feminist who would assert that est denies institutional responsibility for issues like racism and sexism?

Your question reduces to solipsism, and we don't really know how to deal with solipsistic realities—that two things can be true simultaneously, that individuals can take control of their lives and that institutions do bear collective responsibilities too.

The problem with est is that it got caught up in the trappings of middleclass California affluence, but that doesn't negate the kernel of truth it imparts, something well worth contemplating.

Certainly one interpretation would be that we live in a mechanistic world where people out there have power; I have none, thus I am oppressed. Another approach is to try one of these gimmicks—for instance, if you put out positive vibes you can change what happens to you. It does sound silly, but when you do it it seems to work.

Remember the mechanistic view of the world is far from a complete picture. It doesn't do any good just to say, "I'm oppressed." Things change—politically, socially, whatever—-when people take responsibility to do so.

The argument of est was that you really have to take responsibility for your—and the world's—experience, and not to use the est philosophy to your own advantage. Changing consciousness, after all, always starts with the individual.

What if all homosexuals were to positively will themselves to hope for a solution to AIDS instead of just acting powerless over it? The Christians are putting forth lots of positive vibes that AIDS will kill us all off. The sad reality is that we have no way of counteracting this because we're so modern that we don't believe in any of this.

Your commentary assumes an existing gay community capable of response. Do you think this is a valid assumption, given the proven impotence of our community in certain parts of the country?

When we talk about the gay community, we're talking about a tiny percentage of homosexuals. The number of people actually patronizing gay places, social or economic entities, is actually very small. There are large numbers of gay people that we know nothing about, whom we're not reaching at all. Let's face it: There are more of them than there are of us. And we do have an obligation to reach these people. But the question that afflicts us, as on so many other points, is how?