© 1992 Rich Grzesiak, all rights reserved.

The Queen of Hollywood

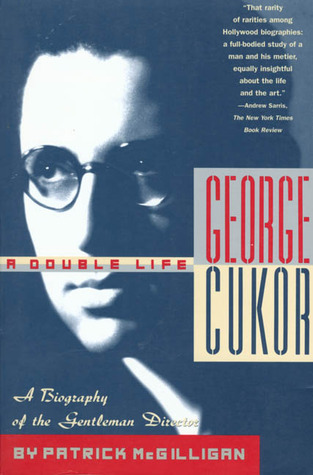

Writer Patrick McGilligan will never die from modesty. "There's a movie in my book for a very smart director," he tells me, and I find myself admiring his understandable cockiness. This self styled lower class Irishman from Wisconsin hits the jackpot this month as he blazes down the publicity trail of TV and radio to promote George Cukor: A Double Life [Saint Martin's Press; $24.95/hardcover]. Subtitled "A Biography of the Gentleman Director," his biography traverses a glitzy geography only people like Kenneth Anger and Boze Hadleigh have mined successfully, the secret world of gay Hollywood from the perspective of one of the most powerful, influential and esteemed of film directors, the late George Cukor.

Cukor, who died in 1983 at the age of 83, earned the impolitic moniker of the Queen of Hollywood by virtue of his envied, and for some hated, directing of the brightest and best motion pictures manufactured in the film capital. His directorial filmography reads like a cross section of the campiest, wittiest, most elegant stories brought to the screen: The Philadelphia Story, Adam's Rib, Camille, A Star Is Born [1954 version], My Fair Lady, Travels with my Aunt, The Women, the list is seemingly endless and virtually unrivaled by any competing film director of his generation.

Yet the personal dimensions to Cukor's greatness unavoidably deal with his homosexuality and even the late director himself had great difficulty tapping into the energy which made him the special person he was. McGilligan tells the story of Cukor's life from a self admitted desire to be tasetful for a classy guy. "My book is not an outing of anybody," he'll tell you in one breath, while minutes later he'll relish an opportunity to dissect what it is that made Cukor A Great Gay Guy.

Not everyone loved George Cukor. His endless quest to surmount his gayness and his Jewishness propelled him into an idolatry of the rich which can truly nauseate. The dark side of this sensitive "women's director", renowned for his capacity to draw sterling work from the Garbos and Hepburns of his day is best glimpsed in an apparent caricature by novelist John Rechy drew of him in The City of Night: "a tight, skinny wiry old man with alert determined eyes," who emerges in McGilligan's words as a "hoary old queen, fawned over by his male 'discoveries.'"

Cukor may have been an elitist demimondaine, but he was an artist capable of extraordinary achievement, and in understanding how his personal life mixed the worlds of film stars, homosexuality and art, we get a much better glimpse of gay history of the mid-twentieth century, as seen from above by a "gentleman" who, being gay and Jewish, never did quite succeed at fitting in. He was ousted from the director's job on Gone With the Wind, according to his biographer, largely due to the bigotry which surrounded him.

McGilligan has smashed open the glass closet encasing Cukor's life and rendered a must read title for those who pride themselves on being literate about gays in the film world. I talked to him at extraordinary length and began by probing Cukor's majestic gay self. Here's how it went:

Rich Grzesiak (RG): In reading through George Cukor: A Double Life, I found myself trying to imagine what it would be like to be alive today and, like the late George Cukor, living as the "Queen of Gay Hollywood."

Patrick McGilligan (PM): It was hard enough to imagine the world of 30 or 40 years ago. Trying to imagine what such a lifestyle is like today is difficult. I'm sure that today it is much more sectorized than it even was then.

Back then there was a community, even if it was one of disparate types, but now there really is not a community—there aren't studio contracts and people who see each other in the film studio commissary everyday. I'm sure there are many more people who are openly homosexual at the same time there are a great number of people who are secretly gay or in the closet.

I wouldn't call George Cukor the "Queen of Gay Hollywood" in his time, I just said that in his close circle some people kind of jokingly referred to him as the "Queen of Hollywood," particularly in terms of his rivalry with Cole Porter as being someone else who might be considered that high up in the social hierarchy, who had the best home and the best guests, and the best clientele The friend quoted in the book who uses that term for Cukor himself observes how upset he would have been to be called that And that friend would have never made such a comment to Cukor's face.

RG: When I first learned of your book, my immediate reaction was, "What gay journalist has chosen to write about George Cukor?" I hadn't heard of Patrick McGilligan. So I automatically assumed you were the cinematic Randy Shilts. I do notice in the liner notes of the book that you are married and have several kids. Due to your love of cinema, you have a very broad tolerance for George Cukor and his homosexual circles.

PM: I wouldn't say it was because of my love of cinema. Are you asking me if I am gay?

RG: I don't want to ask that question as it's none of my business, but I'm fascinated and impressed that you took on this project because a lot of folks who write about this area would have been uncomfortable writing about many of the gay particulars of George Cukor's life.

PM: Well, it was the opposite for me. I think you'll see that the book is dedicated "To Eddie and Stella and everybody else I got to know." Eddie and Stella are, of course a straight couple who were excellent sources on the early parts of Cukor's life. But everybody else I got to know refers to some people who have to remain nameless as well as to some people who are named in the book, but who I didn't want to single out because there were so many who were so very kind.

I was in theater for years and I'm not judgmental about anything I'd say I am judgmental about anti-Semitism or right wing things, but not about what I consider to be liberal or left wing things in the least.

I was not uncomfortable [researching Cukor's life] and no journalist ever asked me if I was gay. The ADVOCATE printed that I was heterosexual, but its interviewer never asked me that question. I don't know [chuckle] where he got that information.

RG: Your wife perhaps?

PM: I'd say it was a leap of judgment on his part. I am quite sure there are married people who are gay. I don't, however, answer that question ["are you gay?"] because the book we're dealing with here is not my biography.

Nobody ever asked me if I was gay, tho' They looked at me very carefully and talked to me very carefully and got to know me very slowly.

RG: These poor souls who interviewed you obviously trusted you on that point.

PM: and I trusted them. I'm telling you that usually when I finish a book I have a stronger feeling for the people I got to know as I do for the person who is the subject of the book. In researching the Cukor book, the people I met I liked very much. Some were very courageous to speak to me. Some, too, were very courageous to meet me and not speak to me All, I thought, had to come from another time period and cross a bridge in order to listen to what I had to say and think about the life of George Cukor. I admired that greatly.

Some people couldn't do that—folks who lie outside the category of homosexual men, someone like Katherine Hepburn. She found it difficult to talk to me in contemporary terms.

You must realize that most of the men I saw were middle aged or older; most were discreetly homosexual and hardly of the sixties and seventies generation of openly and flamboyantly homosexuality. Some of them were in the closet and had led very quiet and inconspicuous lives. Almost to a person, you would never have heard of them before. These individuals were so discreet you can't even pull clips on them (from a reference source).

RG: So, are you up for some tough questions for the nineties West Hollywood crowd?

PM: By the way, we've been discussing whether I was broadly tolerant. I don't even look at it that way. In most ways I prefer homosexual to heterosexual men, I always have and I always will. I hate to say men as opposed to women because in a lot of ways I prefer homosexual women to heterosexual women. I find theirs a very attractive sensibility I consider others who don't share my sense of openness to be broadly intolerant.

In many ways it was a leap of understanding for me to go back and think what it was like for a person of the 1920, 30's and 40's, with the psychology of someone like George Cukor. That was the challenge of the book. As I observe in the afterword of the book, people told me it would be impossible to figure out [that epoch]. I'm not sure they're wrong; it probably is impossible to figure out. I think I scratched the surface and gave everybody a good taste.

And it's nice to have a good taste of what George Cukor or a person like him was like, although there weren't too many like him. He certainly was very individualistic in his style, although he certainly was of a type.

RG: I would suggest that there were people like him but none shared his degree of success.

PM: Maybe I'm being unfair to people like Mitchell Leisen who was a very good director, but I think Mitchell was much more flamboyant [Editor's Note: McGilligan claims Leisen, "a former costumer turned director, carried on openly for many years with a top cameraman."].

Leisen was a very good director but I think he was much less guarded with his life than Cukor was. Cukor compartmentalized his life brilliantly.

RG: Cukor was very discreet about his homosexuality. Given that it was the twenties and thirties that we were talking about, at one point in your book you write that his discretion points to a certain shame regarding Cukor's homosexuality.That style of discretionary shame was quite prevalent in Hollywood during the forties and especially for someone like Cukor.

PM: Note that while Cukor never spoke of his homosexuality in that way, but his very close friends said to me that they felt that in one way or another he expressed it in a kind of shame.

There is a subtle point in the book that Cukor's sexuality was definitely furtive. There were times when he felt that it was not only against the social norm but maybe against what ought to be normal even from his own standpoint.

Yet I don't think it really haunted him greatly. I think the shame came about in the ways that it collided with his career. It hurt him and the shame occurred in interactions with people where he might have been treated shabbily. I think there was some shame in the Gone With the Wind episode. There definitely was some shame in the way he was treated at M-G-M, whereas normally, when you consult encyclopedias, he is held as M-G-M's great contract director, yet in reality M-G-M didn't understand him in the least. Or, at a minimum, not too many people at M-G-M understood him or they thought they understood him as a "women's director."

I think George Cukor felt shame in the latter [being a "women's director"], but that wasn't something he put on himself but something other people put on him.

Was he proud of being homosexual? I think yes and no, as much as anybody is proud of being anything. Most everybody is conflicted about what they are and it's hard to project back in time and try to see what kind of pride and guilt he had. Cukor had some guilt and he had tremendous pride. Towards the end of his life, there was no guilt, and there was even more pride.

Yet George Cukor was unable to cross that bridge into the new world of declaring himself openly gay or anything like that. He flirted with it in the sense that he hung out with people who were known to be openly gay, people like Christopher Isherwood who were declaring themselves to be gay at public rallies, but who made him very, very nervous. That was something that professionally he thought would always hurt him. It was proven at times that it did hurt him. otherwise he would have written his own autobiography.

RG: There's a real paradox in the character of George Cukor having to do with himself and his gayness, namely, his belief that he couldn't write well. Yet what comes through in the pages of your book is the sense that as reassuring as he could be of other people, as understanding of people's feelings (as he demonstrated with actresses and women), he couldn't do the same for himself. George Cukor couldn't reassure himself about his own degree of talent. My point is that George Cukor, deep down, didn't understand himself very well at all, so when he wrote things about his life, there was nothing to reveal.

PM: Katherine Hepburn said he had put so many disguises on that he really didn't know himself. I think she's right. Hepburn's profoundly on target there. Cukor carried on so many perfect disguises that in the end he opaqued himself.

RG: In asking George Cukor to declare his homosexuality, we are fundamentally asking him to declare his very self, and for someone with his psychology, asking him if he was gay is really a highly rhetorical question.

PM: One of the most poignant moments in George Cukor's life is when he starts to write his autobiography. A series of eminent writers toiled very hard on this project with him. Nothing got written and no one can understand that you have the wittiest and most colorful person in Hollywood who will regale you with stories at any dinner party and whose own life you know is fascinating, yet when you sit down with him and try to construct it into a book, nothing comes out because George Cukor is constantly leaving his real self out of every witty story he tells.

Meanwhile, inarticulate, rough and tumble film directors like Raoul Walsh and William Wellman are dashing off autobiographies right and left that are readable and fun. That, again, is a bridge he couldn't cross because he wanted to write a book about himself in part as a self promotion, yet he didn't want to write about himself. So it is a paradox.

The writer Paul Morrissey tried very hard to put together a book of Cukor's letters and there wasn't a book there—there were too many gaps.

RG: Cukor has a solid reputation among the screenwriters and novelists he worked with for being so terribly, very faithful to the letter of their own words. Could the reason be that he didn't trust his own impulses in that area?

PM: That's what editor Edward Dmytryk and others claim, yet I think it's nice he trusted the writer and not his own impulses. The history of Hollywood is one of trampling over the work of writers and Cukor is beloved by his writers for, if nothing else, honoring the script. Sometimes he embellished it with stylistic things they did not feel comfortable with; other times he didn't fix the script as some directors could do.

A lot of directors who couldn't write their autobiographies or couldn't write about themselves or who had problems being personal in their writing rode roughshod over writers and made them miserable.

This admirable trait of faithfulness to other's writing is also evidence of the double life of someone who felt terribly insecure about his own writing and yet at the same time was a tremendous friend and boon to many writers.

RG: George Cukor was celebrated, gay, and loved by some gays yet needless to say not everyone who was gay in Hollywood loved George Cukor. I guess I'm referring to that old cliché of When Queens Collide: a syndrome whereby egotistical gay men don't find themselves very tolerant of other egotists in their midst.

PM: I'm not sure it was all that or all about being gay. You must remember that while we use the term "gay" here not even the word "homosexual" existed in gay parlance in the thirties and the forties. So all this repartee is just your and my vernacular.

Cukor shows up in John Rechy's novel The City of Night as a thinly disguised caricature through a very contemptuous portrait. Incidentally, I don't upbraid Rechy for his portrait because a novelist can use his artistic license to write anything he wants.

Let me put it this way: people who knew George Cukor in the twenties and thirties and forties were well aware of his snobbish instincts and his arrogant, judgmental sides. I can't say you can attribute all of that to being gay. I think he was sought to identify himself with a higher class of people to some extent. This made him very snappish and not the most popular person with some circles of gay people. Yet to a large extent he chose these circles and he couldn't care less about those [other] people, whoever had that opinion of him. Perhaps critics who did not like him made him feel bad.

RG: Yet there's a sarcasm to George Cukor's persona that many people would find offensive.

PM: especially if you were excluded, which John Rechy was not, apparently. He was invited up.

I met George Cukor while he was alive and I found him to be extremely contemptuous of me. He instantly sized me up for what I am, a lower middle class Irish type from the Midwest. My type would go way down on the ladder of people who would interest him in the slightest. Cukor wasn't in the least bit kind to me or pleasant or cordial. On the other hand, he's not the only person in he history of the world to behave that way to me. I don't think it had much to do with his gayness per se.

RG: How were you able to get past your feelings of being hurt by Cukor and become his biographer?

PM: It didn't affect me in the slightest.

RG: Why?

PM: First of all, I came to him at the time of The Blue Bird (1976) and I was fully aware that the filming of that movie was a disaster not of his own making. I feel compassionate toward the people I write about even when I don't like some of the things they do. I try to get inside their minds or to at least achieve a compromise between my mind and theirs. I felt very sensitive and compassionate about him. Looking back on the evening when I met him, I was quite annoyed and rather pissed off and felt very much that I was a lower middle class Irish kid from Wisconsin who was above my own and below George Cukor's station in Hollywood.

I'm familiar with that behavior as I've done thousands of interviews and some people treat you wonderfully and others shabbily, and I don't see why it should affect what you write about them. I was familiar with George Cukor's body of work and knew he wasn't a schmuck even though he was acting like one. I realize that behind that crabby facade was a wonderful, great director in the twilight of his career. I needed to respect George Cukor for what he accomplished no matter what he said to me.

RG: A true professional, you are!

PM: Why not? Even The Blue Bird, which was an abysmal film, isn't the stuff of which would make me observe that the person who made it was a creep. When Cukor directed Rich and Famous , Pauline Kael assailed it as a "limpwristed fantasy." I don't find that sort of comment perceptive.

RG: What offends me about George Cukor is his myopia about the rich.

PM: He's an elitist!

RG: His adulation of the rich is pure bullshit. There's nothing special about them in this or any country.

PM: again, I looked at it from the perspective of the arc of Cukor's life—how he struggled, how he was self made, how he sought to identify himself with these completely fabulous people.

There were some things I didn't put into the book because I found it difficult to document: there were certain circles which excluded George Cukor from the upper class because he was gay and Jewish. I found this accusation very credible when I first heard it, but difficult to document in the book and hard to bring up in a tangent. So I saw him carving not so much a place for himself at the top but a little refuge. I tried to view it in a more compassionate way. But I don't endorse Cukor's elitism—I find it comical and poignant at best.

Cukor was better with those movies [that Garson Kanin wrote] when he was dealing with the middle class which was a milieu he was more familiar with. Those are more real, more credible movies. Cukor was also very good when he was dealing with subjects like bring Liza Doolittle up from the gutter as that was his own life story.

Films like The Philadelphia Story or Holiday, which he is broadly identified with—please remember that those are Philip Barry's works first and foremost and secondly they are done by Donald Ogden Stewart. In the book, I illustrate how these stories evolved and wound up in George Cukor's hands. they are done marvelously but I don't think they reflect only Cukor's point of view but everyone else who participated in them, including Katherine Hepburn's, who is The Real Thing. When you talk about The Ruling Class, you talk about The Real Thing. George Cukor wasn't born to the upper class, and I'm not even sure he died upper class.

RG: But George Cukor did die, we do know that! (1/23/83). Even the rich do die.

PM: He was definitely an elitist, but he was an elitist from the age of 19.

RG: Even elitists die.

PM: Yes. He even offended people at the age of 19. I don't know how much of his snobbery was gayness, if any at all.

RG: I believe there are also people who are offended by sarcastic gay Jews and some of them bear the name of Clark Gable.

PM: Apparently, Cukor's barbs could be very venomous. I find this is true of a lot of directors.

RG: For someone like Clark Gable, who as an archetype of masculinity might have been insecure in his maleness, someone like George Cukor could be poison.

PM: Cukor was treading on territory with Gable in a way that he thought was being sensitive. The Gable-Cukor interaction is too complicated to being reduced to his being Billy Haines' trick one night, although that certainly from Cukor's point of view was one of the key factors that decided against him.There is no question that Gable, at least according to my sources, was anti-Semitic to an extent. On the other hand, I did talk to people who swore Gable was not anti-Semitic. I talked to Gottfried Reinhardt, for example, who worked with Gable for many years and he couldn't believe that Gable was in the least bit anti-Semitic.

To me it sounds very credible that Gable had been anti-Semitic and that he had been Billy Haines' trick, and that he didn't want to play the role of Rhett Butler in the first place, and Cukor pushed him to use a Southern accent which had the effect of making Gable very nervous. Yet which film critic asked is there any doubt that Gone With the Wind is a women's picture anyway? GWTW is a book written by a woman, and has a heroine who's pretty incredible and it's all seen from her point of view. Gable was supposedly worrying that Cukor would throw the picture to Vivien Leigh, who became his close friend very quickly. Yet Selznick used Cukor as a scapegoat because there was enormous financial difficulties due to the delays in filming and there were script problems. Supposedly this undercurrent between Cukor and Gable reached its climax one day and Gable stalked off the set.

That incident gave Selznick the pretext to shut down production and fire Cukor. It really was an ignominious thing because Cukor all along thought he was Selznick's friend. He believed their friendship would prevail It was an event he could never explain in public and it was something in Hollywood that people sort of understood. I tired to flesh it out by getting as many points of view as possible, including Cukor's, who regarded it as a stabbing in the back.

Ironically, not only did Cukor rebound from this episode and direct some of his best films, but Selznick basically went down hill from that point on. It is almost like The Punishment of the Gods. Nevertheless, Cukor and Selznick maintained good relations—Cukor was The Ultimate Politician.

The other day, a woman at the bus stop handed me a copy of the New York Times' review and said to me, "I didn't know that Clark Gable was such an awful person." Of course, the New York Times fudges the version Naturally, the Times doesn't retell the Billy Haines trick episode, either.

Of course, that woman at the bus stop didn't really understand that what she was really asking me was, "Was Clark Gable so awful as to actually call somebody a fairy?"

I had to think about that, because from what I know of Gable he was an interesting person. I guess he was just a human being and anti-Semitism was one of his foibles.

RG: Anti-Semitism is a socially and politically incorrect foible, too.

PM: More so today than back then. Gable probably had good qualities. I'd like to think so.

RG: The American military has trouble dealing with heterosexual Jewish officers in their midst. I am astounded that George Cukor, a homosexual Jew, would ever delude himself into thinking, as he apparently did when he was in the service, that he would somehow succeed at being promoted into the officer ranks of the Signal Corps, no less.

PM: He enlisted late in the war [as a private]. He never got a firm answer on why [he wasn't promoted]. Director William Wyler and Anatole Litvak were officers, and they're Jewish, aren't they? There's a long list of Hollywood directors who made it into the officer ranks except for Cukor.

RG: The American military is not renowned for its plethora of great Jewish admirals, generals and the like, is it?

PM: Cukor could never understand why he didn't achieve officer rank. It was a thing of desperation for him to achieve that. Again, here's a guy who's an elitist who's forced to be a "noncom" [non-commissioned].

RG: Here's a great example of how elitist Cukor is hoisted on his own petard.

PM: I think it was because he had an arrest record and his secret was known to the military and they couldn't deal with that. Of course, you find many, many homosexuals who served in World War II. Most of Cukor's inner circle served in the war, some as officers. But Cukor was conspicuous.

RG: You make the point in your book that Cukor recycled a lot of his life into his movies. I'm thinking here of his mother's death, used in Camille. What examples can you offer me of how Cukor recycled his gayness into his movies?

PM: In writing the book, I tried not to do that in a real strict fashion because I didn't think it was fair to write things like, "This scene is an example of George imagining himself as a woman."

I do believe that Katherine Hepburn was for him the ideal leading lady not just because she was beautiful, but she possessed many of the qualities he would imagine himself as having if he were a woman: adventuresome, ethereal, mannish. Cukor was very attentive to female characterizations, from wardrobe to hairdo to the very writing of a women's role in a script—whether it was logical or sensible for them to do certain things.

His being attentive to women's roles didn't show a neglect to men's roles so much as an understanding of the particular aspects of the women's roles and a very fine understanding of the feminine sensibility. He was acting himself out.

RG: There are people who would take what you just verbalized and say that Cukor's behavior in this regard points to a good exemplification of what they as a gay cultural ideologue would describe as a gay sensibility in the cinema, which Cukor's filmography epitomized.

PM: Garson Kanin said to me, "I don't think there's anything swish at all about George's films." Of course there's a lot less [swish] in the films that Kanin wrote for Cukor than there may be in some other films. Some of the films, like the ones he made in World War II, are campy, to put it mildly; some, like Sylvia Scarlett, are obviously allegorical about himself.

RG: Let's Make Love [a 1960 musical starring Marilyn Monroe and Yves Montand] has a particularly gay flavor to it.

PM: But it would be regardless, because of Marilyn Monroe Some more than others The ones which were more like that people knew about at the time and have talked about since. I don't think I've evoked any new material here but I tried to point to how they relate to certain things in his personality.

Most directors don't put part of their own life into their movies. When Cukor drew from his mother's death to direct the death scene in Camille it's a very ambiguous connection. He did give an emotional resonance to things, particularly to women, that a lot of male directors could never have approached. Being a writer, it is definitely harder for me to "write" a woman than it is to write a man. It's just harder for me to understand.

Most Hollywood directors were men and they didn't understand women, if they were having a menstruation cycle and what that might mean to the way they might behave on the set or act or feel. Cukor had a highly attuned sensibility to women. He was able to identify with them. Even among homosexual directors, my guess is that this quality was rare.

RG: If a woman is menstruating and going through a very emotional period, as a result I would tend to avoid dealing with difficult subjects with her.

PM: I don't know what I would do, necessarily, but I refer readers to a quote from Tallulah Bankhead in the book, where she makes an allusion to Cukor's understanding her moodiness during her menstrual cycle, to his not behaving "as if you've contrived the complete female anatomy as a personal affront to him." Joe Mankiewicz told me Cukor would complement women on their dress or ask to meet their mother or do anything to put people at their ease or feel comfortable in a role.

Absolutely no one questions that Cukor got great performances out of people, be they men or women, throughout his career. These are special sensitivities that arose out of his personality and character and being homosexual, the whole package. I don't try to separate out these factors because it's too hard.

RG: You suggest that "Reassurances [supplied]" should have appeared on Cukor's business card, and that is part and parcel of his persona.

PM: Joe Mankiewicz claims that other men form Cukor's era were trying to fuck the women, which made some happy and some very nervous. George specialized in the nervous ones as well in the ones like Katherine Hepburn who weren't the least bit uptight.

RG: If I could have been a guest at one of Cukor's Sunday afternoon soirees around his swimming pool—surrounded by some of the most attractive men in Hollywood—I can only guess just how much Vaseline one could scrape off the edge of that pool.

PM: I tried to write a "tasteful" book, and I reached for a classy tone because Cukor was a classy individual. I could have written a more lurid book, more of a Kenneth Anger/Hollywood Babylon book. I did cite one episode involving people who would run off to the potting shed but I don't think there was much of that because I think that's where you met people and exchanged phone numbers—very high toned for the most part.

Conspicuous, bad behavior and "swishy men" displeased Cukor. The Sunday afternoons would be a prelude.

RG: Would someone like campy Paul Lynde have fit into Cukor's Sunday afternoon soirees?

PM: In Hollywood in the thirties I couldn't possibly estimate what percentage of the film colony was gay, but it was very large. Of that percentage only a very small number ever came into contact with Cukor, personally or professionally, because he was an elitist. Flamboyant people made him nervous, but sometimes he accepted them.

Lynde's reputation for bibulousness and campiness were qualities Cukor would have only tolerated in very old friends and women.

I was privy to stories involving people who are alive and I can't do anything with that information because they are not out of the closet. "Outing" them would have been bad judgment on my part.

RG: Folks would argue the point with you about "outing."

PM: "Outing" is intended as some form of biblical vengeance which i don't disagree with at all. I am not sure I agree with it but the few instances I've seen I haven't had a problem with.

Rich Grzesiak screams at the mere thought of screening the 1954 epic Demetrius and the Gladiators.