© 1993 Rich Grzesiak, all rights reserved.

"Tim and Pete tries to convey in print what people really think rather than what they should think or what's P.C … My fantasy was to leave readers so infuriated they'd throw down the book and march right out to a gun store because they wanted to see the finale so bad they realize the only way it'd happen is if they make it happen in real life!"

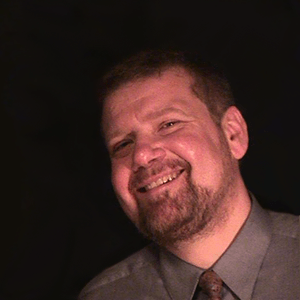

So growls novelist James Robert Baker, an angry youngish older man whom the Los Angeles Times hailed as "angry, raunchy and unapologetic," his wiry body color photographed in a 1993 interview with his legs splayed at the crotch -- for more than decorative effect.

This guy is a rage-aholic, methinks. Myself no stranger to anger, I had to meet the scribe who forsook the lucrative occupation of screen writing (successfully, that is) to craft a novel about two estranged contemporary L.A. lovers who commingle with a kamikaze group of gay terrorists bent on giving ex-Prezinut Ray-Gun a permanent new part to his hair, for Memorial Day, no less.

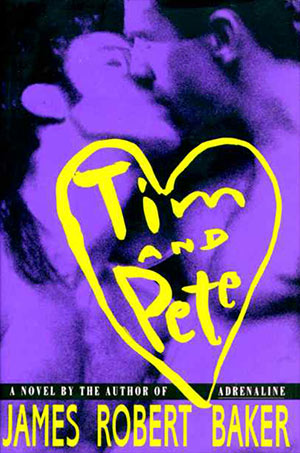

James Robert Baker (no relation to the ex-Bush Secretary of State), 40 going on 20, looks like the kind of reformed but lovably educated bearded punk who'd pick a fight with a Marine thrice his size just for the sheer outrage of it all. He admits to being at death's door from various problems a decade and half ago, but seems resurrected into the role of a latter day Jeremiah cum gay novelist, eager to browbeat us into rethinking the contemporary tragedies which the desiccated among us take for granted (AIDS, drugs, death). His Tim and Pete [Simon & Schuster; $20/hardcover], recently reissued in softcover, has got to be one of the angriest romps through the gay Southern California hillsides since … well I can't think of such a bittersweet comparison.

It's filled with little nuggets like the character Tim's fantasy about editing an HIV-Humorzine, a magazine of AIDS jokes which runs out of steam when its puss of retinitis jokes collapses back into horror again.

Tim and Pete are a couple of characters so dissimilar they must be in love, the one a film noir specialist and museum worker, the other a recovering blue collar addict-alcoholic whose attendance at A.A. meetings doesn't deprive him of time to keep up with a group of conspiratorial gays bent on avenging the horror of AIDS -- by blowing away a few right wing fanatics. As their friends die all around them, you learn Pete's mother works for a right wing Congressman who resembles a Dornan or Dannemeyer…

Tim and Pete represents, in the author's words, a kind of violent death bed humor until one realizes there isn't enough humor to contain the horror of contemporary Los Angeles it bivouacs through. It rumbles from raunch to realism to romance, from AIDS-flavored update to being "fucked blind" to campy descriptions of cars (the 1970 Buttfucker), and impassioned flashbacks to love at sex's first sight, if you will.

Of the many scribes I've tracked down over the years, Baker is one I had to meet and talk to, just to see if the ferocity of such a wicked writer's prose would be sustained in real life. He's an angry man who betrays his rage only occasionally. I found myself adoring him as a person, completely charmed on a human level, but grossly disturbed by the violent fantasies he rhapsodizes in his book. Baker's a guy you either love or hate, but one thing I know for sure: I respect his audacity and craft. He thinks L.A.'s gotten worse since the riots ("makes Blade Runner look like a Disney tourist attraction")—no wonder he's a self styled nihilist.

So we spoke , agreeing on very little, overlooking a polluted Pacific from a house in, appropriately, a slide area. Here's how it went:

Rich Grzesiak (RG): Your book makes no bones about its rage toward Republican extremist ideologues. Are you at all concerned one will pick up a copy, figure out where you are and potentially do violence to you?

James Robert Baker (JRB): No, those people don't scare me. I don't think you could live being afraid of people who don't agree with you. I don't care; I'm ready for them. Let's just leave it at that, O.K.?

RG: Has the book brought in any hate mail?

JRB: Not really … That doesn't really concern me. The closest I've come to that sort of thing has been in the pages of the L.A. TIMES. After the profile the TIMES did on me there were some nasty letters a week or so later, what I call polite nastiness. Sure, I'm aware when you deal with this sort of subject you can set people off, but what's the alternative: be a timid little lamb and say nothing ever and go through your whole life not making waves?

RG: I would be scared … Some of the Dannemeyer clones are pretty proficient at being crazy.

JRB: I think gay people have already spent too much of their lives being scared. I think that's a lot of what the book is about in a sense. It's about not being scared. I think the best defense is an offense, to paraphrase one of my characters.

RG: Some of the characters live off their own anger almost, and that's good and bad. It certainly clarifies the kinds of things they want ….There's Pete, one of the angriest people in the book, yet at the same time he's trying to put his life back together and reach for more serenity. Isn't that a contradiction, really, in the way his personality is constructed? How can you be so angry and crave serenity?

JRB: I don't think so, no. I'll put it like this: I think I have a lot of political anger but I don't think I'm an angry person in my private life.

RG: Let's not get confused here: I was talking about Pete, not you.

JRB: But I think the issue is the same because the question gets raised, does anger preclude more positive feelings? I think you can be angry politically and not be an angry person in a pejorative sense. I think anger is an appropriate response on a political level if you're gay now, but I don't think that means you're angry in terms of your private life and interpersonal relationships or people you care about. I don't see any contradiction.

RG: So to put it in movie star metaphor, you can be a Roseanne Barr politically but a Donna Reed on a social level, is that what you're saying?

JRB: If you want to put it that way. I think gay people are still being talked out of their anger too much. I think there are a lot of systems in place to convince gay people they shouldn't be angry, especially people with AIDS, that anger is a stage—the Keebler-Ross stages of reaction. There are all these therapeutic forces in place to keep people from acting out some of the more extreme political violence scenarios in Tim and Pete which I have mixed feelings about. I have great ambivalence about those kinds of scenarios. On the one hand, I'm not advocating PWA's turn themselves into human bombs, but on the other hand I have to admit that if I clicked on CNN and heard somebody had blown Patrick Buchanan's head clean off, I'd be elated, and to say otherwise would be a lie.

RG: So you're comfortable with angry political demonstrations and angry stylization of our political agenda?

JRB: Oh, definitely! I think that in my heart of hearts, groups like ACT-UP have not gone far enough.

RG: How far should they go?

JRB: Well, again, that's a good question. I don't know if I'm proposing a political action or agenda. I think Tim and Pete explores what would happen if people went much further. I wanted to look at that. I think I've heard enough talk over the last 10 years about people going much further that it interested me as a subject for a novel, to explore how that would play out. What are some of the moral, ethical dilemmas if you crossed the line into political violence?

RG: That's the responsibility of the artist to use poetic license to fantasize those scenarios. That's one of the things that intrigued me about the plot.

On the other hand, from seeing political groups of all stripes, not just gay ones, I've noticed the angrier they get, the more diffuse their message seems to be and the more the reaction is to turn off whatever their agenda is.

JRB: Well, you're looking at things from a pragmatic political point of view, which is valid in the real world but as a novelist I'm not concerned with that, or what's rational or prudent.

The arguments for political violence in the book are ultimately emotional and existential. You notice there's a sense the wrong people are dying; AIDS has killed the wrong people. The wrong people are still alive. The wrong people are circling the Clinton Presidency like vultures, drooling over 1996 and bashing the fuck out of gays on the local level in the meantime.

Why are those people still alive? That's the question the book asks. So the anarchists who decide to kill these people are doing it for a kind of existential rationale rather than because it would be politically prudent. You could make a strong case it wouldn't be, that if somebody actually did that, it would freak everybody out and cause a tremendous backlash. That's a valid argument. In a novel, I can do whatever I want.

I think a strong case can be made that political assassination actually does change things. If you look at the assassinations in this country in the 60's you can certainly see how it affected history in a very profound way. So if you killed right wing figures, you'd also be altering the course of history, and eliminating people who might very well be president in 1996 and those who are making bashing gays their number one issue right now.

Those are the issues the book deals with … questions of whether it's moral or not to wipe out a whole church full of people in order to get Ronald Reagan. The text essentially concludes it's not moral to do that. But if you're assassinating specific individuals, the text essentially concludes there is nothing wrong with that, it would be a really cool thing to do.

RG: I struggle with some of the world views of your characters. I think they invest more power in extremist conservatives than they actually have. That's a natural byproduct of being around very hysterical, extremist oriented people. Whenever I'm see (Representative) Dannemeyer on C-Span, it's the Jackie Gleason Moment: comic relief. I'm always fascinated by what distance people keep from him on the floor of the House, how much of a veritable pariah he is even in Republican circles, except here in Orange County.

JRB: Well, I think Dannemeyer has done a lot of damage … But on a larger level, one of the strategies of the book is to re-exteriorize homophobia. I think American culture has done a very good job of convincing gays to interiorize homophobia, convince them if they're angry they should see a therapist for some sort of personal problem. The characters in Tim and Pete tend to aim their anger at the representatives of a homophobic culture rather than at each other—which is another thing gays are very good at, taking it out on each other. We have our own ways of doing that the same way that blacks, the Crips and the Bloods, take it out on each other.

RG: Everyone knows other minority groups do their own self bashing just as gays do…

JRB: Right, and I think gays have their own special ways of doing that, but Tim and Pete argues for the idea of going to fight the real enemy and realizing where the voices of self hatred come from. They don't come out of the mist, they come from real people in the real world, people like the Dannemeyers and the Dornans and the Helmses. To me that's much healthier, to aim the anger at people who are oppressing you rather than take it out on each other in little playlets of oppression.

RG: I would suggest that from Memorial Day of '92, when Tim and Pete is set, to Memorial Day of today, the world has changed, even if only slightly. At last I'm beginning to feel at least a margin of hopefulness in terms of what's been happening: we have a President who's at least receptive to contact with the gay community and pushing a gay agenda. The polls taken in the wake of the announcement Clinton would issue an executive order banning discrimination against gays in the military are hopeful: I expected far more hostility against gays measured in those polls, and it really hasn't been there [the majority of polls indicate a plurality of support for gay rights].

JRB: … I think it's still too early to say what Clinton is gonna be about, figuratively. There are people who are already going off on him like Larry Kramer at the March in Washington recently. I think that's a valid tactic to take at this point. At the same time, I'm glad Clinton got elected rather than Bush but the right wing has made gay bashing it's number one priority of the nineties. These people are the Pat Robertsons and the Christian coalition: [folks] who are actually calling for the death penalty against gays. [The rightists] are very busy on local levels fielding candidates and a plethora of new anti-gay initiatives. Most people have realized just having Clinton as president is not gonna be some kind of big, patriarchal savior for gay culture. These battles are gonna have to still go on. There's no guarantee of how long Clinton will be president. That's a real concern. People had this sigh of relief when he was elected but it's premature to think everything will be fine now.

Larry Kramer's beef is that we haven't done shit about AIDS yet, AIDS is still killing people in droves … What's really changed?

RG: I put Larry Kramer right up there with Grace Metalious (Peyton Place) in terms of his moral and aesthetic sense: If he stopped writing his melodramatic faggot books, we might all be a lot better off. Larry Kramer will die of anger: he is permanently enraged. People like Larry Kramer are just as distorted in their views of gay reality as the Liberace-esque Pollyanna's in our midst. I tend not to trust people that far to the margin.

JRB: I have a lot of respect for Larry. It's easy to criticize him, and it's true he's strident, but he's probably done a lot to save lives and he's taken very unpopular positions. He and Randy Shilts are two gay figures I really admire; they're very different. Shilts has been very articulate, he's not a rage-aholic like Larry Kramer.

RG: There's a serenity to Shilts which Kramer wouldn't experience even under the influence of Sominex.

JRB: But I think we need both tactics manifested.

RG: I part company with you re: the empowerment you're giving right wing fanatics. By putting gays as their number one agenda, what's gonna happen is they're gonna further marginalize themselves with the public at large, as they tended to do in the last election.

JRB: I hope you're right. Those tactics did backfire.

Let's not overplay this: what I'm basically saying is that the anger in Tim and Pete is still valid. It's not as though, oh, well, everything's fine now that Clinton got elected; You don't have to be angry anymore … It's important to say my book is about a lot more than that: primarily a gay relationship in the age of AIDS, dealing with what that entails. Tim and Pete certainly deals with these larger political questions of violence and terrorism, but much more than that … It's not like I'm trying to make some strident political point. My book explores a lot of the realities in gay life now.

One of the main things I wanted to do was explore a gay relationship, two boyfriends who are both probably HIV negative: how they negotiate a survival route through a world where people are dying all around them … How they deal with the baggage of past relationships. They're both old enough to have lived in a pre-AIDS gay lifestyle: how do they deal with that? how does that impinge on an attempt to find some kind of bond?

RG: L.A. is a neat place to be if you're gay and alive in the 1990's—people here have lives far more exotic than their East Coast counterparts. That's what Tim and Pete demonstrates to me.

JRB: You're right, I wanted to deal with their relationship in all of those contexts, but I didn't just want to study two boyfriends in isolation. I think that's where L.A. has been an interesting place because as they move geographically across the city, Tim and Pete encounter other racial groups. I wanted to show the interplay between two white guys and blacks—the misconceptions they have, etc. The blacks Tim initially thinks are homophobic hip-hop guys turn out to be gay.

RG: I think the style of masculinity of California men across the board tends to be more tolerant of differences, including homosexuality: the ratio of different types of groups is probably higher than any other part of the country … Just as the two of us are sitting literally in the slide area this afternoon, people here live right on the edge: that's what makes their stories so mesmerizing.

Tim and Pete as characters don't seem to fit as a gay couple, their differences seem to clash too violently to ever make their relationship work… Opposites attract, maybe, but in the real world they also tend to repulse.

JRB: They're not the same, there's common ground in terms of sensibility. All I know is I've met gay couples who tend to be very different, and it works. I think opposites can and do attract. My sense is they complement as much as they irritate each other … There's ultimately a sense their relationship is being salvaged…

RG: One of the sexiest aspects of the book is they never make love to each other in the course of the plot except in flashbacks—there's an erotic charge which sparks Tim and Pete.

JRB: I did it that way deliberately. I didn't want the book to have a sense of closure either in terms of the relationship or the action the anarchists are planning at the end.

The anarchists' action has brought me criticism which I anticipated—people want closure, they like to read a fantasy acted out in a nice little book so they can later put it down and say, well, that was just a book. I deliberately wanted to deny people such a false sense of closure when the people the book targets are still alive in the real world. It almost would've been similar to writing a book about somebody discovering an AIDS cure, but there is no AIDS cure in the real world, so it would've been false to do that.

I wanted Tim and Pete's relationship to be a question. People read it different ways: some people think they have enough in common to work it out, especially since the action takes place over a day's time. You don't know if they're going to have a fight the next day and break up again…

RG: Actually I got so irritated with Tim and Pete's lover's quarrels I wanted them to split…

JRB: But they don't hate each other, they love one another a great deal. Relationships have flash points and you don't stay together because all's nice over time that's not real world, either. I did want to leave open what would happen and let readers make their own call on the prospects of that relationship.

RG: Tim and Pete does end so you feel like you've fallen over a cliff: the reader doesn't know whether the anarchists have blown away Bush, Reagan etc. It ends the way a contemporary screenwriter anticipates a sequel.

JRB: I have no intention of writing Tim and Pete: The Next Day. So many issues Tim and Pete struggle with are unresolved in real life. It would've been incredibly false to provide a cheap, violent catharsis at the end. To be honest …semi-facetiously put, my fantasy was to leave readers so infuriated and dissatisfied they'd throw down the book and march right out into a gun store because they wanted to see the finale so bad they realize the only way it'd happen is if they make it happen in real life [cackle].

RG: [spoken like Reagan] Hold on, is there a part of James Robert Baker that likes to enrage people? Is there an imp in you that loves to stupefy people angrily?

JRB: No, but look: I don't want to make it sound that this book is some type of frustration device. It "gets people off" without providing a cheap blow out…

There's a lot of satire in Tim and Pete which readers miss. There's dark, black humor, too.

It took me a long time to decide how to write about AIDS. Tim and Pete is not an AIDS novel … I didn't want to craft a plot about someone's decline and death … I wanted to find a course through that [without obsessing over it] … that pointed to a survival route instead of just grief.

The world of gay letters lost one of its most superb scribes when James Robert Baker passed away on November 5, 1997. I'll never forget meeting him: those piercing eyes, that electrically male persona. The view from his Pacific Palisades residence was breathtaking. I even asked if that incomparable view reminded him of the house James Mason retires to in the 1954 A Star Is Born. He smiled.

Jim Baker was an original in a world of cloned out clones. He had a sense of literary, moral, and political vision which is all too rare among contemporary writers. His anger was so compelling, so much a part of his personality and his literature.

There is just sadness and silence as I think of him this rainy December eighteenth, nineteen hundred and ninety seven, Anno Domini. May God grant unto him eternal rest.

See his obituary below. —RG

James Robert BakerSaturday, November 15, 1997

Home Edition

Section: PART A

Page: A-20

James Robert Baker; Satiric Novelist, Cult Filmmaker

By: MYRNA OLIVER

L.A. TIMES STAFF WRITER

James Robert Baker, novelist and filmmaker whose over-the-top satire enthusiastically blended humor with rage and violence, has died. He was 50.

Baker, perhaps best known for his novel Tim and Pete, committed suicide Nov. 5, 1997, in his Pacific Palisades home, said his friend Ken Camp.

The writer's other books include Adrenaline, about two gay fugitives, Fuel-Injected Dreams, a sendup of the rock music industry, and Boy Wonder which satirized the film business Baker came to loathe.

Trained at UCLA film school, where he won the Samuel Goldwyn Writing Award, Baker began his career as a screenwriter. He left after five years, steeped in experiences he would use for Boy Wonder.

"I felt like a door-to-door salesman going to all these pitch meetings," he told The Times in a 1993 interview, describing film executives as "rabid, hideous morons."

Baker's fourth novel, Tim and Pete, told the story of a gay couple in post-riot Los Angeles who fall into the company of an assassination-prone group of AIDS kamikazes. Their motto is: "If I get AIDS, I'm going to take someone with me."

A self-described anarchist, Baker denied that he was advocating such action. "I think assassination does change things … But I'm not really calling for violence," he said. "It's a novel, not a position paper."

But the rage that Baker clearly felt over gay-bashing and the loss of friends to AIDS permeated his writing.

Another hallmark was graphic sex and bad language, or, as he described it, "raunch with intelligence."

"I'm just trying to capture the way people really talk and think," he told The Times. "I want to write like Keith Richards [of the Rolling Stones] plays guitar… Using genteel prose to describe sex is the equivalent of doing [a Stones album] on a harpsichord."

Baker estimated that his books, which received mixed reviews from critics, sold about 25,000 copies each.

A fifth book, Right Wing, about a conservative philosopher and would-be presidential candidate, was published on the Internet.

Baker was also known for an underground film, Mouse Klub Konfidential, about a Mouseketeer turned gay bondage pornographer, which scandalized the 1976 San Francisco Gay and Lesbian Film Festival.

Undaunted, he followed that with another film cult favorite, Blonde Death, about parricide in Orange County.

Brought up in Long Beach, Baker is survived by a brother, Douglas, and his partner, Ron Robertson.

©1997 Los Angeles Times