© 1992 Rich Grzesiak, all rights reserved.

Will the world ever tire of hearing about nutty, old, aristocratic Englishmen?

If so, let's not tell Quentin Crisp, Sir John Gielgud, Sir Robert Morley, Evelyn Waugh, Masterpiece Theatre fans, Terry Thomas, Monty Python, Graham Chapman, Dudley Moore, Peter Cook and who knows how many other bright souls who have mined this rich motherlode.

I guess if we could warp back to 1066 A.D. and William the Conqueror, we'd find them even there.

Let me put this phenomenon in slightly more contemporary terms. Imagine, if you will, a David Bowie, more artistically and literarily inclined (in lieu of musical), alive and well in the England of the Roaring Twenties, with a fortune devoted to acquiring exotic works of art and using seven different colors of ink to compose a novel, handwritten, in the amount of a half million words, which never, ever came close to being published? Imagine that same outre aristocrat as mentally ill, reclusive yet brilliant, esteemed by the likes of Willa Cather, Cecil Beaton, Garbo and Truman Capote?

Meet Stephen Tennant, who takes top billing as "England's most legendary and outrageous aristocratic eccentric," a bizarre esthete who, according to biographer Philip Hoare (pronounced : "whore"), when asked by his Edwardian father what he wanted to be when he grew up, replied, "I want to be a Great Beauty."

Just like Woolworth heiress Barbara Hutton (whom he befriended, too), Mr. Tennant traveled with cases of perfume. His lunches fed people like the young Truman Capote soup with candied violets (which Capote found repulsive). His antics formed the source for the character Sebastian Flyte (best known to fans of Brideshead Revisited ). For Stephen Tennant, pleasure always came before business, and serious pleasures they were—outrageous, excessive, crazed, narcissistic in a way and on a scale some would find mental health material nowadays.

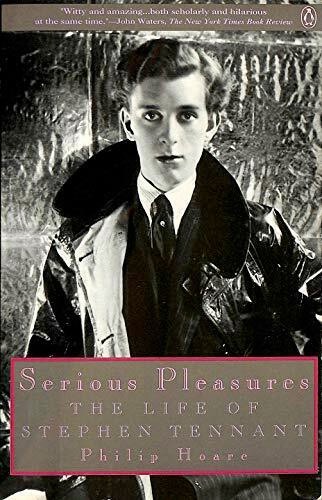

Journalist Philip Hoare met Stephen Tennant shortly before his death in 1987. He claims this visitation gave rise to an obsession which in turn yielded a "biopic" entitled Serious Pleasures: The Life of Stephen Tennant [Penguin; $15/softcover].

If Quentin Crisp had a grandfather, he must have been Stephen Tennant. Trying to summarize the story of this strange man beloved of E.M. Forster and Virginia Woolf is impossible. So let's just start at the beginning, shall we?

Rich Grzesiak (RG): Where did Stephen Tennant's wealth derive from?

Philip Hoare (PH): His family invented a formula for bleach in England in the eighteenth century. During the eighteenth century they were able to capitalize on that. They're not really landed gentry at all—they're not aristocracy or trace their antecedents back to William the Conqueror. They're quite new money really.

RG: How appropriate! This recherché queen derived his largess from bleach of all things. Perhaps it was nature's revenge to give the originators of the formula for bleach a son named Stephen Tennant.

Well, then, as one materialistic girl to another, Philip, why biographize Stephen Tennant? Why not pick a latter day "Tennant," a David Bowie, for example, and write a biopic of him?

PH: Funnily enough, I've been a big David Bowie fan since the Year Dot (Zero). There are a lot of parallel reasons for why I like Tennant and Bowie, as they both possess that same otherworldliness, the gender bending, their ability to shock and yet still really charm and entice people.

When I saw the photo of Stephen sporting the mackintosh which is on the jacket of Serious Pleasures, I really thought to myself, God, that man is a star—how could anyone look like that back then [in 1927]? Bowie has that alien look about him which approximates Tennant's look in the twenties. The very idea that someone could get away with that appearance then fascinated me.

The other factor which motivated my research was the day I met Stephen Tennant, one of the most memorable of my life. Serious Pleasures as a book was an attempt to explain the effect that one day had on me.

My obsession with Tennant was the basis for it all. The actual writing of the biography was incidental—it was me working out my obsession, which remains with me even now.

RG: The esthete Stephen Tennant and his eccentric world is Masterpiece Theatre material. Do you have anyone in mind who could play him with any degree of astuteness?

PH: I think it would have to be a complete unknown because the "name" actors wouldn't want to risk their careers. When The Naked Civil Servant debuted in England everyone thought that the actor who portrayed Quentin Crisp (John Hurd) would be perceived as a "camp" sort of person. Yet that role completely "made" him and brought him international attention.

You need someone to risk all to adequately portray Stephen. That is a hard task to fulfill casting wise.

Were I to cast the role I would find some really fey, aristocratic, young Englishman. Or it could be an American. But It would have to be someone who was really fey

RG: Has their been any interest in Serious Pleasures from the cinema or television?

PH: Merchant Ivory has. In fact, James Merchant used to go visit Stephen occasionally and was very impressed at the idea. I think Merchant Ivory has so much product in the pipeline they can't even consider what to do next.

There's been quite a lot of interest from BBC and ITV in filming a documentary on the life of Stephen.

RG: Americans would take the view that the British are hung up about the eccentrics in their midst. But I'm fascinated anyway. Why do the British obsess so much about such eccentric characters like Stephen Tennant?

PH: The British have a very odd Puritan streak in them Americans love the extremeness of Stephen better, while in England he is just a little too bit outré.

Having said that, the English tolerate eccentricity. They won't ignore it. They'll play it down by not talking about it, whereas in America it's celebrated—they love people for being unusual. It's odd that Quentin Crisp had to come to New York to be the immortal being he is. The English attitude to eccentrics is very equivocal; they don't quite know how to deal with it. They know that the world sees England as being full of eccentrics. I don't think the English quite like it. At one point they think it's really not quite respectable and ought not to be talked about. Their attitude is of the flavor, "Oh, Uncle Stephen [Tennant], he was rather strange and we don't talk about that."

RG: Stephen Tennant makes Quentin Crisp seem like James Mason. My theory is that because the English demonstrate such a lack of feeling that people of extreme feeling and uniqueness like Stephen Tennant give them an excuse to actually talk about a feeling, if you will. It's safe territory to let your feelings out about eccentrics.

PH: I talked about that point with Quentin Crisp last night. Stephen knew such serious people—E.M. Forster, Virginia Woolf, Vita Sackville-West. Because Stephen was so extreme, when these types of serious people were in his company all their buried, exotic feelings—the things they really wanted to let rip with in a terribly outrageous way—these feelings seemed to find release around him.

So, for example, E.M. Forster would suddenly become "gay" in the old sense of the word ("merry") around him—he'd exude the qualities of playful and silly, all those qualities quite unlike the kind of serious writer he was.

RG: British expatriate (and California resident) Christopher Isherwood and his lover (Don Bachardy) paid a visit to Stephen lengthily discussed in Serious Pleasures. It's almost as if they were looking to be shocked by Tennant and emerged being astonished instead by how much they weren't appalled by him. Isherwood-Bachardy were so overwhelmed by the garishness of Hollywood that when they met Tennant they looked for something to condescend to and they couldn't. They found instead the "real article."

PH: Isherwood's and Bachardy's visit to Stephen is very telling. Cecil Beaton brought all his friends to meet Tennant—Garbo, Truman Capote, et cetera. Beaton knew that Stephen was the sort of person that no one ever encountered. So he played two things off: he liked to show off Stephen the Eccentric but he also liked to see the reaction of people like Isherwood, Garbo and Capote. Capote, for example, complained that he didn't like lunch because there were candied violets in the soup.

It is so funny. A lot stems from Cecil's need to play games with people. Yet a big factor here is Stephen Tennant's acting like the theater person he should have been. Beaton describes Stephen's waddling out of the room while Isherwood visited only to re-enter and resume the performance. Again Stephen might well have found his true metier as an actor. By being on stage he would have externalized all those madcap schemes of his. Sadly, he didn't pursue it.

RG: You are raising a lot of feelings in me because of the many contradictions that an extreme personality like Stephen Tennant brings. On the one hand, he had so many fabulous acquaintances, yet at the same time his was a life of extraordinary seclusiveness and isolation. In trying to intellectually resolve the contradictions in Stephen's behaviour, I am finding a lot of self hatred present there as well. Am I on the right track here?

PH: A lot of it boils down to his mental state. In retrospect I wonder if I gave enough weight in Serious Pleasures to the fact that Stephen had been mentally ill in his life. You can ascribe the way he lived to a certain lack of mental stability. That was after the fact and not a matter of cause and effect. I think Stephen always knew that he would never bring himself to do the things that Cecil Beaton and Rex Whistler did. To go out into the world, become a part of it and be a commercial person, to sell one's self—Stephen thought that was very vulgar. When Stephen Tennant learned that Stephen Spender framed his letters, he was offended by that as he regarded letters as very private things not meant for exhibition. These beautiful, multicolored, painted letters he sent to people were just his personal communications.

So, too, was the situation with respect to the book which was Stephen's lifelong work, Lascar, which he wrote over about seven times. It was as if he couldn't let Lascar go; he couldn't bear to let it emerge as part of a greater world.

A lot of artists have to face this thing where they create something which is a real expression of their innermost feelings. Yet there comes a time when we have to let these creations of ours go and enter the real world—Stephen couldn't do that. Yet of course what we might say is that Stephen was afraid that he and his work might have been found wanting, that public opinion would find him not good enough. That's what he said to Rex Whistler when Rex said that. Whistler told Stephen that "you draw as well as Aubrey Beardsley—why don't you do more? Are you afraid that people won't find you as good?" Stephen answered him yes, it probably was that.

RG: How sad and tragic. I suspect that would explain why Lascar was never completed, correct? Lascar consumed 500,000 words and reached no summation?

PH: The really interesting thing about the voluminous Lascar was that it was all written in different shades of ink! Every sentence of the manuscript might be a different color of ink. It is just an extraordinary document.

Lascar was a cyclical thing that he invested all his life and creativity in. He kept it by his bed to rewrite it and then piled it to the other side of the bed, rewritten. Lascar was a part of him just as much as Wilsford, his family home was, which he also filled with the most unusual kinds of art: moss covered fishnets, jewels, seashells, pieces of fabric, feathers. All of these were his attempt to create a world of fantasy. Even Lascar was a fantasy of living in Marseilles as part of this rough trade world which he might have experienced in the 1930's, but very briefly and now is reliving again and again in his mind.

Ultimately, I suppose it's sad but why should it be sad that somebody didn't actually achieve something? Why does anyone have to achieve anything? Why do you have to complete a book? Isn't it good enough that you produced it for yourself to satisfy your own creative needs?

RG: It's not sad so much as it's painful to read about someone who was struggling with so much poor mental health. Let's face it: if we really wanted to be unkind—and I'm sure Stephen Tennant encountered a few such souls in even his sheltered life—we could just glibly dismiss him as a nutty old queen.

PH: Absolutely and people did. Let's face it, in the fact that he died virtually unknown and uncelebrated That's why it happened: he was dismissed as this ridiculously eccentric figure. Someone in 1927 described him as "surrounded by strange creatures with a few feathers where his brain should be." This was how Stephen was viewed yet people like Willa Cather and Jean Cocteau thought Tennant was a valuable human being with a very good, intellectual brain.

Of course the Forsters and Cathers were completely exasperated by him because he wouldn't get his act into gear. So if someone said to me, "Oh, yes, Stephen lived a worthless life, did nothing, accomplished little," I'd say you're welcome to those opinions. For myself I think it's worth celebrating someone who can live like that and who can maintain a certain integrity.

The very concept of Stephen's living only for beauty: O.K., so he's ignoring some of the awful things in the world. You need people who can live like that almost as a gesture in the face of all of the ugliness of the world. Tennant was someone who could live and testify to a certain kind of appreciation of better things. He wasn't a material person in that way.

RG: With certain classical music composers like Mahler or Tchaikovsky who left incomplete works, others have been able to complete them. Mahler's Tenth and Tchaikovsky's Seventh Symphonies prove that can be done. Could something similar be done by a literary critic with respect to the great unfinished written work of art of Stephen's life, Lascar ?

PH: I don't think so principally because it's still only exists in Stephen's mind. Supposedly there's a structure there which one could piece together, but you get the feeling in reading it that it is still in Stephen's mind from where it can and will never emerge.

PH: I don't think so principally because it's still only exists in Stephen's mind. Supposedly there's a structure there which one could piece together, but you get the feeling in reading it that it is still in Stephen's mind from where it can and will never emerge.

RG: And Stephen Tennant's mind isn't exactly the kind of thing the American Psychological Association would like to clone out.

I do struggle with the underlying tenets of the theory of estheticism ("art for art's sake"). It's good as far as it goes as a theory of art if you want to view it in a very utilitarian way, but in the age of A.I.D.S. and other tragedies it does become untenable for a working artist.

PH: Well, obviously, it's gone as Stephen Tennant was the last person who could live that out. If Tennant were born in 1986, with the life he'd be destined to have now, he couldn't do it.

RG: Lives like Stephen Tennant's with that intense preoccupation with the artistic soul living for art's sake, doesn't that invariably lead an artist into behaviour which is terribly cold? Some of the incidents portrayed in your book which involve some of Tennant's semi-cruelty, even when viewed through the prism of his mindset, don't emerge as moments of very bountiful human nature.

PH: Stephen didn't have a realistic view of the world. If we could go back to his childhood we'd see its seeds there.

RG: In Serious Pleasures you portray Stephen's reactions to death: he would just shut out the death of anyone, turn it off and pretend it never happened. I'm a child who deals with friends who died of AIDS and that style would not help me in living through 1992.

PH: I don't know if Tennant valued people enough in that way, really. I don't think he valued other's existences. People were adjuncts to him and to his own existence.

His mother brought him up. He didn't have a peer group with which he interacted like other young people did. He didn't play with other children like you and I would. His mother eve dressed him as a little girl until he was 8 years old.

Stephen's mother even wrote down the things he said as a young child and published them . She took him as a child to spiritualistic meetings. It was such a weird way of bringing someone up. It's going to fuck you up!

RG: It certainly would! Nowadays if a woman were to treat her male child like that I think she should be sentenced to a women's prison somewhere. It's cruel and indicative of the fact that Pamela, Stephen's mother, was an aristocratic bitch.

PH: Pamela got away with it because she was so charming and everybody loved her, but she was a bitch, she was, and she struck the fear of God into him. People still alive who remember her claim it was like a wave cresting when she entered a room.

RG: What a Messalina! Even if Christopher Isherwood would pop up the subject of politics with Stephen it wouldn't connect with his seclusionary world.

PH: True. Tennant would actually tell people he admired Hitler because of his mustache and the way he parted his hair and that starry look in his eyes.

RG: I do object to that.

PH: His world was hermetically sealed so that no news of the outside realm ever leaked in. Tennant had nothing to judge the sort of wild statements he would make. You can't read anything into that I'm afraid. You can blame him for being ignorant

RG: Stephen Tennant fell in love with California and he even told Isherwood he wanted to live there. He visited it. Could Tennant have accomplished a move there considering all the limitations on his mind and manners?

PH: It certainly would have been quite difficult as he never learned to drive; it'd be quite difficult to get about. He would have wound up some kind of recluse in some pueblo style manse in the San Fernando foothills. God knows how he might have gone down in California of the 1930's.

RG: But the truth is that even in the thirties California had such creatures. There is such a character in Evelyn Waugh's The Loved One (set in Los Angeles of the late forties): Sir Frances Hensley, the art curator on the staff of one of the big studios (it's the role Sir John Gielgud played in the 1964 filmization of that book).

PH: Yes! And people would have probably outdone Stephen Tennant as an eccentric even in Hollywood of the forties.

RG: In reading Serious Pleasures, I was struck by the almost constant references to the plague of the twenties of the thirties, tuberculosis (TB) and consumption. The unread, uneducated mind tends to forget that before AIDS ever was there were a whole host of diseases and maladies which ate away at mankind. TB was the AIDS of Stephen Tennant's generation.

PH: Susan Sontag's essay on illness as metaphor is the best summation of that phenomenon. There was no real treatment for TB until the introduction of penicillin in the forties. So you have bizarre treatments for TB with people like Katherine Mansfield going off for treatment in Switzerland—a treatment involving her sticking her head in a cow's manger! There is an entire body of literature from Charlotte Bronte to Thomas Mann. There is a lot of literary significance to consumption as a metaphor for a state of being, an otherworldliness which consumptives felt --- becoming estranged from the world, drawing back from it. People became objective with their lives and also slightly fatalistic. People who were so ill also became highly sexed. It's very interesting that Stephen's affair with [his lover Siegfried] Sassoon grew, blossomed, withered and died throughout the progress of his TB. As Stephen got better, his lover Siegfried Sassoon was jettisoned. There's a whole book to be written concerning the effect of TB upon literature, I suppose.

RG: I got the impression that no matter how creative Stephen was, he really had an aversion to sex. Even though Tennant found men very attractive, the very act of homosexuality revolted him. Why?

PH: I'm sure that Pamela, his mother knew where Stephen's real instincts lay, and did her best to instill a certain sexual self hatred I think he was basically an ethereal creature and lived for the fantasy of it. His sketch books are filed with these ribald drawings of sailors.

RG: But that's as good as it got. With all his money, did Stephen ever play the voyeur and pay to watch sex?

PH: There's no indication of that at all, although he could have done so. The trouble was that he was such an aristocrat—not that that ever stopped anyone—but he was very retentive in that English sort of way.

RG: Would it be fair to describe esthete Stephen Tennant as a gay Willa Cather of a very aristocratic bent? A pioneer to a brave new world of a revived estheticism? Were these the qualities which so obsessed him about that American writer (Cather)?

PH: Stephen would have loved your description because Willa Cather is really who he would have loved to be.

RG: I would think that Stephen's proclivities would make him much more prone to wanting to emulate the photographer/novelist Carl Van Vechten or the fin de siecle novelist Ronald Firbank.

PH: He valued Cather much more highly than he would have ever esteemed Firbank. Theirs (Tennant/Cather's) was a very odd pairing, wasn't it? She was such a stern disciplinarian who didn't even approve of Oscar Wilde. God knows how she connected with Stephen.

RG: Well, Willa Cather was from Nebraska, wasn't she?

PH: Yes, that says a lot. In fact, last year I went to Nebraska to lecture about Stephen and Willa and half the audience there thought it was fabulous while the other half was plainly wondering, "What's our Willa doing with this painted creature?"

Shortly before my talk I overheard someone say, "I already know much more about Stephen Tennant than I ever wanted to know, thank you very much."

Cather was a great Anglophile and she was a tremendous snob who loved the fact that this aristocrat was just fawning over her and writing her fan letters. She also really valued Stephen's opinion and thought he had a very good critical mind. He was entertaining, too, in that he was totally opposite to all of the rest of her friends. He was an exasperating breath of fresh air for her.

RG: Is it coincidental that Willa Cather and Stephen's mother (Pamela) both "stroked out," one through a cerebral hemorrhage, one from a veritable stroke? Did these women short circuit on their meanness?

PH: Their deaths had a pivotal effect on Stephen. The death of his mother launched him into a bout of TB and brought his "Siegfried Idyll" [his relationship with Siegfried Sassoon] to an end. The death of Cather during the war precipitated severe mental illness in Stephen's life, too.

RG: What was the "trouble" with the law you refer to in Serious Pleasures which Stephen got into, which eventually led to his being placed in a mental institution for a period of treatment? You don't really explain it in the book at all.

PH: I couldn't discuss it in the book because the manuscript had to go to the family lawyer prior to publication for his approval. The problem was that Stephen was arrested for importuning a soldier in Salisbury Station.

RG: I don't think I have heard the word "importune" since Eisenhower was President. What an elegant way to describe it. The one time Stephen Tennant decides to pursue a serious pleasure of sexuality, they arrest him for it.

PH: Stephen was put on remand and part of the sentence was

RG: that he was sent to the loony bin! How cruel!

There's another interesting parallel between Stephen Tennant and Evelyn Waugh. They both eventually—Stephen earlier in his life and Waugh later on—got bound up with Roman Catholicism. Stephen gets into this cult of the Virgin Mary.

PH: As someone who was brought up as a Catholic, I connect with it, too. I think it's a love of ritual, that exoticism which Catholicism has which Protestantism has not. All these priests dressing up in chasubles and maniples and surplices

RG: The mystical parts of Christianity.

PH: Beyond that there's an extremity about Catholicism which appealed. It's a logical progression if you begin the process of conversion religiously. If you're like Stephen, you want to go the whole way: hair shirts, fasting, that sort of thing which Catholicism still entails There's a belief in the reality of heaven and hell and purgatory

It also was in vogue to become a Catholic. Edith Sitwell and Firbank went off and converted. Aubrey Beardsley went back to being a Catholic. There's a whole subtext to this which I don't feel qualified to go into.

RG: Interestingly enough, in Los Angeles a month ago the prelate there, Cardinal Mahoney, advocated a return to a Legion of Decency type approach to film viewing. The odd thing about the Catholic Church today is that it is anything but mystical; it's pedantic and the ritual has been popularized to a vulgar level.

PH: Oh, yes, with folk Masses and the like.

RG: Where are the Stephen Tennants of today? Is Quentin Crisp right observing that that world is dead, done and over with?

PH: Oh, yes. Anyone can walk down a Los Angeles or New York street wearing makeup, a mackintosh and a fur collar. It doesn't shock anyone.

RG: On the other hand it's quite shocking to get mugged and raped if you walk down a Los Angeles street all rouged up.

PH: That's part of the reason why you don't get Stephen Tennants. As much as Stephen intimidated people, there are times when he might well have been bashed. He was not, however, the sort of person who traipsed about on the public transport. He didn't have that problem.

RG: So one gathers.