© 1989 Rich Grzesiak, all rights reserved.

In the fall of 1939, an event occurred which forever transformed popular American entertainment—a Portuguese speaking woman with the exotic name of Carmen Maria do Carmo Miranda da Cunha, more popularly remembered as "Carmen Miranda," took Manhattan by storm.

For gays (and drag queens everywhere), of course, Miranda's influence is unparalleled (one has only to see just a few moments of the Busby Berkeley extravaganza The Gang's All Here to understand what tutti-frutti hats and campy double-entendres are all about).

34 years after her untimely death (from a massive coronary at the age of 46, on August 5, 1955, after taping The Jimmy Durante Show for NBC-TV), most of her films remain available to the general public through cable television or the videocassette, and there are even periodic revivals of her flicks at festivals around the world. (Her flicks include the fabulous That Night in Rio, Weekend in Havana, Greenwich Village, and a host of other 1940's hits for Twentieth Century Fox). Her flicks abound at film festivals around the world.

And so it fell out that American entertainment met a Portuguese speaking woman with the exotic name of Carmen Maria do Carmo Miranda da Cunha. More popularly remembered as "Carmen Miranda," she took Manhattan by storm.In the fall of 1939, when Broadway was being hit hard by a slump partially caused by the then World's Fair, Carmen opened in a musical called The Streets of Paris that quickly became the sensation of the season—which ultimately catapulted her to legendary stardom in Hollywood. The cavorting, sensual singing, and all around campy personality she epitomized (not to mention headdresses piled to the ceiling with fruit) wreaked a sensation that had never before, and rarely since been equaled.

Just who was Carmen Miranda and why do gay men so especially honor her memory, still? What is it about Miranda's cultural appeal that transmitted such a shock wave, a veritable earthquake, through the staid channels of popular American entertainment? What were her special contributions to films and music, and what price did she pay for her inimitable artistry? Why was she so reviled by Brazilians during her heyday (and frequently mistaken as Hispanic), and why is she so revered, right down to a "Carmen Miranda Museum" in Rio de Janeiro today? How could an international film star who epitomized frivolity and mirth suffer such chronic depression and sadness?

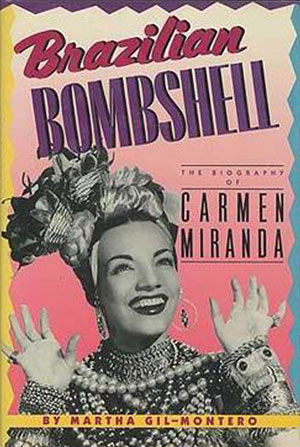

For answers to these questions, I tracked down a wonderful woman by the name of Martha Gil-Montero, who has written the world's first full length biography of the Brazilian Bombshell: The Biography of Carmen Miranda [Donald I. Fine; $18.95/hardcover]. A published poet and translator, Gil-Montero is a native of Cordoba, Argentina and has resided in Washington, D.C. for the last decade.

Carmen Miranda is not an intellectually fashionable celebrity on the order of say, actress Simone Signoret, so I was curious to learn whether Miranda's biographer was ridiculed for researching her? "People laughed at me," she confides. "I began researching her life from the position of those who rejected her. I felt that Miranda's career ridiculed South Americans—ephemeral in a word, but the more I learned about her, the more I realized this simply wasn't true. It became very difficult to convince publishers and editors that they should take on Brazilian Bombshell, because for them Carmen was not serious or interesting."

Even a prominent film historian like Leslie Halliwell writes that Miranda was "always fantastically overdressed and harshly made up, yet emit[ted] a force of personality which was hard to resist." Her biographer claims that what people like Halliwell cannot see is the "immense talent necessary to create this character called Carmen Miranda—part singing, part costume, partly the strength of her energetic personality.

If you find yourself wondering why there has been no biography until recently of so famous a Hollywood star—a woman columnist Walter Winchell dubbed the "Brazilian Bombshell," it's because "no American could write her story because her beginnings are so important. "

Montero told me, "Brazil and the tropics really made Carmen Miranda possible. Her Hollywood years are a consequence of all that, not really the most important part. While I didn't emphasize her Rio days, her roots are very important. I first became aware of her while growing up in Argentina, but she was very popular in all of South America, and her songs, the popular Brazilian music of the thirties which she made popular—remains very popular—it's the music everybody sings there. In Latin America it's not the Hollywood songs people remember her for - it's the 300 songs of her early Brazilian roots, made famous when only Brazilians knew her."

It was the Second World War that initially helped bring Miranda to international prominence. The President of Brazil dispatched her to New York in 1939 to entertain at the opening of the Brazilian pavilion at the 1939 New York World's Fair. Gil-Montero recalls that "Miranda became a symbol at the beginning of the war of the U.S.'s 'Good Neighbor Policy' which tried to ally countries like Brazil and Argentina against Hitler and the Nazis. Her career profited from this gaiety—she was the friendly Latin who got along with Americans. I sometimes think that if countries like Nicaragua had the equivalent of a 'Brazilian Bombshell,' it would have helped her a lot.

Even more interestingly, Gil-Montero told me that "the turban and the ruffles which were Carmen's trademark headdress still exist in her native Brazil - a native 'baiana' look. The fruit on her head in The Gang's All Here was her—and not Busby Berkeley's—idea."

She went out one day and saw those little baskets of fruit for sale in the slums of Rio, and decided to put them on her head, and that's how it all started.

One of the hallmarks of Miranda's Hollywood years was a basic inability to speak clear English, something that persisted in later life. "She could only speak a few words of English at first," Gil-Montero reports. In her first American film (Down Argentine Way), she sang and spoke in Portuguese. However, when she filmed That Night in Rio [1941] she had learned everything by heart, even the replies to her dialogue, so she would know when she had to speak - she understood very little English that was spoken to her. I sometimes think that if countries like Nicaragua had had the equivalent of a 'Brazilian Bombshell,' it would helped her and her career a lot.

To make matters worse, her studio (Twentieth Century Fox) required her to continue speaking in broken English, so she really didn't put any effort into improving it. I think it was probably impossible for her to learn the English language correctly, because she had practically no education. The little she did learn was due to her excellent memory and capacity to imitate sounds.And so, one of the most celebrated of Miranda's mannerisms—her endless capacity to mangle the English language into unending streams of malapropisms—was born. "Get along, you little hot doggies," she cries in one Western scene of a musical she made for M-G-M, while in still another flick she demands to know, "Who left the cat out of the bean?" On other occasions, she was prone to singing about the Latin allure of the "Soused American Way."

The central drama of Miranda's life, in fact, was the extraordinary tension that developed between her American success and her adopted homeland. "Very few people realize that Carmen Miranda was Brazilian—some think she was Cuban or Mexican. Although she was born in Portugal, she grew up in Brazil and tried to do what she could to be as Brazilian as possible, and to promote as much Brazilian music as she could." But when her career skyrocketed in the United States, her fellow countrymen came to resent her burgeoning notoriety, so much so that by the early 1950's, when her own personal crisis with drugs and drink sidelined her, Brazilians found the "Ambassadoress of Good Will" far too American for their tastes.

Miranda's popularity in Latin America was hindered, too, by fierce bigotry. Brazil is not Latin American. Unlike the rest of South America it speaks Portuguese and has a multi-racial culture with much black influence. When Martha Gil-Montero was growing up, even cultivated Argentineans were fond of calling the Brazilians 'macacos' or monkeys. (She doesn't think they do it anymore, as Brazil has grown to be a huge, important country).

She was so different for films of her day - naughty and provocative, the "Madonna" or Cyndi Lauper of her time. According to her biographer, "80% of her magnetism was pure sex appeal. Most of the men who played in films in those days were like Don Ameche - rather dull and stiff, the very negation of sex appeal, or they were closeted homosexuals, like the late and lovably funny comedic actor, Edward Everett Horton. By contrast, Carmen was a sex bomb - the perfect foil for men of that type."

It's interesting to compare the policies of "good neighboring it" of the 1930's and 1940's with the fear and hostility certain reactionary Americans feel toward foreigners and Hispanics today—or to realize that Carmen Miranda's smile and broken English made her such an electrifying ambassadoress.

She was quite free sexually - very Catholic and all that. She was not promiscuous but a free adult woman. She didn't get married until she was 38, so she had a whole interesting sexual life before she got married.

But by 1950, her tremendous work schedule began to take its toll in the form of a drug and alcohol dependency.

Gil-Montero: "She was very close to death in 1943, and after that she never really recuperated. Her physician [Doctor Marxer] was actually in love with her. Carmen took any kind of drug [prescribed to her]: uppers and downers and sleeping pills. She wanted to lose weight, and self-medicated herself. Her maid and musicians tell me that she was addicted to pills, but not to any hard drugs like coke or heroin. Kenneth Anger's assertion in Hollywood Babylon that she carried cocaine in a secret compartment in her high heels is completely untrue - there were never drugs like that on her person or in her home."

A devout Roman Catholic who almost entered the convent as a teen, Miranda became very hyperactive in her later years, and sleeping became a problem. When going on stage, she frequently was afraid and came to rely on pills to get her act together. Gil-Montero claims "the electric shock treatments they gave her in the early fifties for abuse of certain drugs probably could have been treated quite differently. Her weight was a constant problem due to its regular fluctuation. During her last week alive, she had a terrible bout of bronchitis and was taking antibiotics. Her maid told me she knew Carmen took a lot of pills, and she saw her drink a lot the night she died. She told me, 'I could have stopped her, I could have told her to get to bed earlier.'"

She and everyone around her felt very guilty about her death. Gil-Montero feels that "Miranda's career in 1955 was on a comeback, but how long she could have sustained it is not clear. She was beginning to suffer from terrible memory losses, which is how Toscanini's career drew to an end. So I think she died at the right moment. She died after a good performance on TV - what better way to end your career?"

Even so, there are many who ask even today, what if she hadn't died—would her career have endured? Her biographer doesn't have such doubts. "I don't think she could have kept up the pace she was keeping. Her jewelry and costumes weighed a ton, and I don't think her heart would have permitted this strenuous exercise. But TV and disco might have been her salvation." I can see it now - a Studio 54 disco part circa 1979, with Carmen Miranda belting out Brazilian love songs to a disco beat. Carmen Miranda was profoundly campy. The interior of her home bears witness to her extremely campy tastes She had a portrait painted of herself with different kinds of materials—stones and feathers, etc.— the picture was absolutely tacky! Naturally, she had this picture prominently displayed in her home, and loved it.

Today, Miranda's career is the stuff legends are made of, especially for campy gay men, who appreciate her zaniness as no other subculture could. Gil-Montero believes that "she had gay friends but back then they were called queer, and I remember how much fun for her it was that these men were called queer - 'Queer' for her was a magical word."