© 1991 Rich Grzesiak, all rights reserved.

A Couple of Guys, Sittin' Around, Talkin'

Truman Capote once wrote something about California to the effect of "The wind through the winter blows sleep."

His perception applies generously to West Coast gay fiction, a genre within a genre which heretofore has seen no proper springtime. While collections of gay and lesbian fiction abound, one which celebrates the sensibility of gay geography, those skies of peerless blue which symbolize the West Coast's endless vistas of potentiality, has not appeared.

Until now.

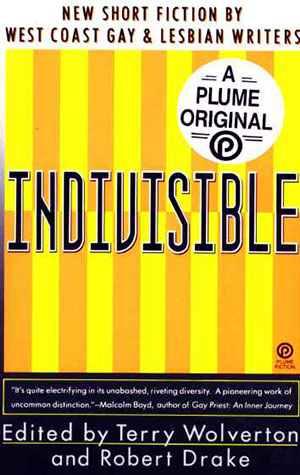

Indivisible: New Short Fiction by West Coast Gay & Lesbian Writers [Plume; $10.95/softcover] "brings fresh vision to the conflicts of gender, race, and sexuality from the West Coast's literary cutting edge. At a point where lesbians and gay men are moving beyond political division, Indivisible represents unity and the need to transcend human differences."

So claim its two editors, Ms. Terry Wolverton and Mr. Robert Drake.

It's unfortunate these two folks have chosen to inject the warm and wonderful bullshit of political rhetoric into the world of good gay short fiction, because there is a resonance, a highly original freedom which the West Coast can give to gay literature. Just as the best gay periodicals are published in the West, so, too, is the most unaffected and daring gay creativity of all types, print, visual, etc. In true "boy, girl, boy, girl" lineup, Indivisible unites 24 provocative pieces of evocative New West vision.

Robert Drake, one of Indivisible's two editors, recently blew through my apartment on his way to a reading by the book's contributors [Terry Wolverton, unfortunately, took ill, and was unable to keep her confirmed appointment]. Drake looks like Bruce Q. Yuppie: tall, lithe, dark haired, bespectacled, serious, intense , the complete opposite of the West Coast gay stereotype. He's recently moved East, yet this book has given him a platform to field questions on the obvious topics, like what makes West Hollywood no West Side, what good scribbling achieves. He looked butch, too, so I thought I'd tackle him on his specious theory of Gay People As One Big, Happy, Co-ed Family on the Road to Political Unity.

For a brief moment, I found myself thinking, "Hey! Remember that piece in The Village Voice years ago headlined "A Couple of White Chicks Sittin' Around, Talkin'"? That's pretty much How It Went:

Rich Grzesiak (RG): Why publish a book like Indivisible? Certainly there've been plenty of books over the years which have anthologized gay and lesbian fiction.

Robert Drake (RD): I was an agent for 4 years in L.A. before moving to Baltimore (last year), and from the outset editors were saying to me, we feel a lot of the new gay writing that's to be discovered is in California. We just don't know how to get access to it So, go do your job and bring us West Coast writers.

With that thought in mind, I learned Terry was leading a series of writer's workshops, so I went to one. We thought of putting together a collection of the best writing from those workshops, some of my client listings, and whomever we would encounter via the grapevine

We were looking for people whose voices were unpublished—only L.A.'s Michael Lassell had published a volume of poetry—people who wouldn't have been heard from otherwise. Their work doesn't fit the guidelines of Men on Men and Women on Women or other anthologies. [We wanted to] give new writers a place to be heard where they otherwise would remain voiceless, which I think Indivisible does. Does Indivisible introduce new styles of writing? In a couple of places I think it does.

We put it together on the basis of West Coast writers we felt should be heard, which needed to be exposed to a broader audience. By no means is this Our Workshop's Anthology It's the product of many workshops and writer's groups and friends telling friends It came from people saying, "They're doing this anthology and now is the time to share your work."

To say that Indivisible 's contributors are intimate friends of ours is not really true. There are even people whose work is in Indivisiblewho I did not meet til I came out to Los Angeles for the publication party.

We did get more material than we thought we would; we did reject some stories.

RG: If all of that is true, then why include a writer like David Watmough? He's Canadian, isn't he? What relationship does Canada have with the "West Coast"?

RD: He's from Vancouver, British Columbia, the Canadian west coast. Canada spans from sea to shining sea.

RG: What is it about California gay writing that has publishers and editors so excited?

RD: Good writing can be found anywhere But publishers find it easier to tap into writing on the East Coast But when you're 3,000 miles away on the West Coast, even if you have a reputable agent located in New York who's good at getting their client represented, that type of writer-editor-agent-publisher familiarity so easy to achieve on the East Coast is not there.

RG: I think a lot of gay readers are real, real tired of "New York, New York" gay writing. The tendency within the publishing industry, centered in Manhattan, is to bring in writing that is easiest for them to get to—the local crowd of scribblers. I guess that's nothing more than a failing of human nature. But do you think there are other reasons why that seems to be the case?

RD: I think a lot of New York writing is certainly meritable. But the West has a frontier mentality to it. It still retains it. 100 years ago, Los Angeles was an orange grove; now it's this sprawling metropolis of 8 million people You don't get this type of mentality on the East Coast.

RG: You mean that type of Horace Greeley, "Go West, young man!" spirit?

RD: That type of "there's elbow room out there" thinking. There's that there.

I keep referring to L.A. and California and that's really incorrect. I should refer to the whole West Coast I don't mean to exclude places like Seattle or Vancouver or Portland or San Francisco. I think that same type of "there's breathing space here" sensibility exists in those places as well.

It's a search for something different. Take Rakesh Ratti's short story "Promenade": could fiction like that have emerged from New York? I don't know I hate to say we haven't seen it yet because it may just have not caught my eye. The stories of Indivisible seem to be trying to do a lot of different things that aren't usually attempted in other gay/lesbian anthologies.

RG: Do you think there are differences between East and West Coast gay readers? Are there different literary appetites in different parts of the country which you'd care to speculate about?

RD: Judging by the readings I've given in conjunction with the publishing of Indivisible , I'd have to say no I thought we'd [do a reading in] New York and there'd be three people there, that only the friends we begged to come would dare show up [chuckle]. Yet the place was packed. We were truly stunned to see a standing room only crowd turn out in Manhattan.

I would say most gay readers are interested in good gay writing and that tendency is a common bond we all share A New York editor bought this collection, after all. So what does that tell you?

RG: It tells me there is still a smidgen of hope left for gay editors in New York.

RD: Either that or maybe we're not as far apart as most people think.

RG: I hate New York, particularly gay New York.

RD: Do you?

RG: There is a line, usually attributed to Gore Vidal, though it's more likely apocryphal, that "New York is where all the great fringes of art combine to form one giant fringe." I believe it.

RD: On the other hand, there's that famous line of Truman Capote's: "For every year you live in Los Angeles, you lose another point off your I.Q."

RG: I'm not so sure the besotted Mr. Capote got that right I love California, I truly do. I think there is a creative spark there quite unlike any place else in the United States.

RD: [Even though I've moved East, I must say] California was very good to me. It gave me a career, a livelihood, and a circle of friends which I'm grateful for.

RG: There is a serious difference in the quality of the gay subculture between California and the northeastern U.S. which I've observed more of a looseness culturally and socially which the East will forever lack. Maybe I'm plugging into the stereotype of West Coast Gay Everyman, but I've noticed it.

RD: since I'm not familiar enough with the East Coast gay world I can't really compare.

RG: If you could set yourself up as a literary god, what kind of gay fiction writing would you encourage?

RD: Writing that affects. I like the feeling you get when you put down a book and you know you have changed, somehow you are a different person than you were when you picked that book up. By that I don't mean you're poorer by $19.95, but the book has impacted on your life.

I like to encourage writing like that. I was going to answer you by yapping about how much I love F. Scott Fitzgerald, but then I thought about what it is of Fitzgerald's writing I admire: his writing has the power to do what I've just described. I finish [reading] it and something inside of me is different, brighter or deeper than it was before.

One story which does that in a style much differently than anything Fitzgerald ever wrote is Robin Podolsky's short story "Dignity/Uniforms/Dignity," which is a shattering piece to read, and to hear it read was a very intense experience.

So it's not so much style. Style is important, certainly. A good, readable style is very important. The content and your use of language to communicate with the reader in an effective transformation to effect an increase in knowledge and brightening of the world is most important.

RG: "Dignity/Uniforms/Dignity" has a real snap to it. It's an MTV video given short story prose form.

RD: It's blunt and direct and doesn't spare you anything and you have to deal with it. It's hard that way.

RG: It doesn't choose a lot of passionate language, its power lies in its descriptive perspective from several different vantage points.

RD: It has the feeling of, "This is what is. Part One like this."

RG: It has so much power of economy you could almost spec out a screenplay from it.

RD: Yes: it's very visual, you see it.

RG: My other favorite story in Indivisible is Trudy Riley's "Highway Five." You can close your eyes halfway through reading it and sense you're living in California and it'll be sunny for days on end.

Did you pay contributors to Indivisible?

RD: Of course. Although not all gay publishers, as you know, are reputable. I had a lot of trouble with Elizabeth Gershman of Knights Press with one of my books. It was simply one of the most awful publishing experiences I ever have had.

That's one example of things that go bad in gay publishing, but conversely there are some great people working in the field. Some of the most brilliant talent is in the field of gay and lesbian publishing. Chris Shelling, the editor who bought this book and supported it from Day One, is certainly one of the finest minds in the business. Plume has certainly done its share to keep gay books in print. And yes, it's primarily because they make money off of them. But they pay their authors.

RG: I do have a problem with the ideological thrust of your book. Why not be "divisible" when it comes to gay and lesbian fiction writing? Just what is there about lesbian fiction that most gay men can identify with? I personally have more in common with promiscuous, straight, unmarried females than I do with most lesbians culturally, sexually, thematically, politically. What is there that should link up gay men with lesbians for any agenda, literary, political, or otherwise?

RD: If you look at it from a political point of view we are both part of the same persecuted minority. Because of sexual orientation, there are powers that be that would rather see that we not exist. Or if we do exist, it would prefer that we be driven underground so polite society doesn't have to deal with our being. Why subdivide an already minority group? Why weaken it through such subdivision? Politically, that makes sense.

From a literary point of view, I think that is the purpose of this collection. We wanted to illustrate our commonalities.

People have a tendency to "read in their own backyards." White males have a tendency to pick up books by other white males. White women have a tendency to pick up books by white women, though most women seem to be more open to reading books by women of other races than I would say men tend to be.

The whole point of this book is something I have seen work in my own life. A white male might say, "I might read Men on Men and maybe I wouldn't read Women on Women , but I would pick up this book [Indivisible ] because of the stories it has in it by men I would also read the stories by the women, because I would just be reading the book. Afterwards I might be more disposed towards picking up something featuring those authors."

Are we really that different? Of course, we're different. Our lives are different. Different people lead different lives. Different factors go into all of that. I think that insisting on separation is limiting and hurtful to our society and to our own personal lives. If you limit yourself to leading the existence of a white male—I use the phrase "white male" in the same sense I would use the word "California"—if I limit my life surrounded by other people who are white men, I don't really see the depth and the color and the richness that brings them into my life.

I don't want something that limiting. I want a life that's full. I think that's what exposing yourself to different cultures and experiences can do.

RG: I believe our differences overcome our similarities, and that simple fact of life is not necessarily bad.

RD: How do you mean?

RG: I mean it literally: women struggle with different issues and want to write about them in a way gay men typically wouldn't. That's not necessarily bad or good, that's just the way it is. To force a kind of cohesion is, if you'll pardon my putting it this way, unnatural. Yes we both want to have sex with people of our own gender, but very little unites us other than that physical dimension. You can hypothesize and theorize about how the genders' differing sensibilities converge but they remain at best theoretical. Am I being clear?

RD: I'm trying to think of times when I've said, "Oh, I have nothing in common with you." Maybe it's the way things are.

I've always had close friends who were women, and close friends who were men and close friends who were lesbians. Some of my best friends are lesbians. The same is also true for people of color. For me to look at that, and think, is there a time that I said, "What you're doing is completely different from what I've ever gone through and there's no way I can relate to that"?

I'm just drawing a blank. Because of that I have to say that the aspects of persecution may be different but the bottom line is that we want to keep people like you down. Does that make sense?

RG: Yes. I just respectfully tend to disagree. It's not that I don't want to be connected to other subcultures, or I want to be divisible, I have simply learned that we are different, and that's the way it's gonna be and it's very hard to force cohesiveness.

I don't feel a whole lot of connectedness to feminist culture or the lesbian experience. I'm not sure I want to. And yes, I think we have certain political goals we can share.

RD: Terry [Wolverton, co-editor] and I have become very close friends. Years ago, Terry was a lesbian separatist. When the AIDS crisis came around, she found that continuing to remain being a separatist when all this healing was needed was morally reprehensible. She ceased her position of being a lesbian separatist.

I am a 29 year old white male who is heart broken over the cancellation of thirtysomething and doesn't know what he is going to do on his Tuesday nights from now on. I am a non-compromising assimilationist: everybody should be able to live in the same world as long as you don't hurt anybody. I believe in the American Dream, I believe in the ideal. I want kids and the whole bit.

With Terry and I you have two people coming from two different ends of the spectrum That two of us can come together and become the close friends that we are to me is a very enriching experience. I've watched myself grow and change because of that. I'm a little hesitant at what I'm saying because I feel I sound like a New Men's Liberationist. Any moment you expect me to start yapping about how I sleep with my spear.

I'm a human being on the face of this earth, and think we really all ought to get along. I have a lot to learn from your experience as a human being; we have a lot to learn from each other and work together toward a better place. And that's great.

I think being divisive [means] I don't really care about what you're about. I'm just gonna take care of myself. I think that's ultimately just stabbing yourself in the foot.

RG: I could follow-up with other arguments to dispute your point but choose not to, as I think they're best dealt with in a book with a political and not a literary context. Perhaps I should close by observing that good writing is good writing, no matter whether it's lesbian or gay. The same rules govern it.

RD: Hopefully, Indivisible as a collection proves your point. In fact two of the stories we both liked a lot were written by women. But I like all the stories—they're all really great.

RG: Ironically, the only story I didn't like is by a man. But read the book, and judge for yourself, dear reader.