© 1989 Rich Grzesiak, all rights reserved.

So how stands the state of this old and troubled (gay) union?

Across the lower 48 states, it's difficult to give you the big picture, except, of course, if we were to send a sympathetic reporter through this glorious land, someone with a flair for both creativity and professional impartiality, an Edward R. Murrow who could update novelist Edmund White's classic 1980 account, States of Desire: Travels in Gay America [Obelisk/Dutton; $7.95/paperback].

Is Neil Miller the de Tocqueville who can fairly and intelligently describe what it's like to be gay in these United States, circa 1989? Prior to interviewing him, I had severe reservations about his skill - after all, he worked from 1975 to '77 as an editor at a very ideological (if not left wing) paper [Boston's Gay Community News] whose polemical style defines forever that quality pejoratively known as "politically correct," didn't he? Sending him to evaluate our state of the union initially impressed me as a ludicrous idea, like sending Nancy Reagan to write a report on poverty in Alabama.

But the more I thought about how committed most leftists in the gay movement are to dedicating themselves to political and social sensitivities, the more it made sense to me. Even if Mr. Miller might be uncomfortable talking to gay cops or queer Marines, he certainly would have a reporter's skill and, who knows, maybe he would "grow" through this enriching experience. (He's no ironclad gay Stalinist either, having contributed to such capitalist periodicals as Glamour and Travel and Leisure.

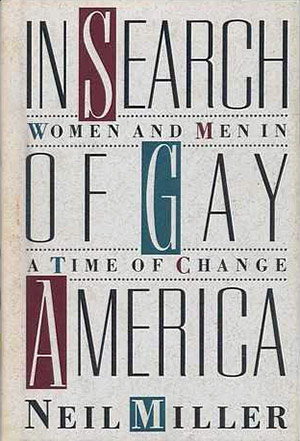

I am happy to report that Miller's new book, In Search of Gay America: Women and Men In A Time of Change [Atlantic Monthly Press; $18.95/hardcover], is probably the best we can expect in lieu of another foray into our subculture's wilderness by Edmund White. He is, at times, happy, witty, and wise, sensitively painting broad, long strokes of our very troubled subculture. At best, he's a crackerjack ace on the order of, say, the late reporter Ernie Pyle; at his worst, he pedagogic and attitudinal, complaining about gays who are too Republican and wealthy for his taste.

Mainly, though, Miller throws up quite a panorama to meditate on as he struggles to record a day in the life of gay America, 1989:

Rich Grzesiak (RG): A moment of déjà vu here: when I interviewed Ed[mund] White nine years ago, I remember how negative that period of gay history was, perhaps best typified by the gay leftist who was so afraid of people harassing him, that he refused to have his name used in States of Desire. I haven't noticed that degree of fear and loathing in your In Search of Gay America.

Neil Miller (NM): There was some of that - I spent a lot of time interviewing a guy in a Southern state who had been a state senator for 24 years. He lost his most recent reelection bid; there were many rumors he was gay. But in the end, he would not permit me to use anything (for the record). If there is fear, it may not be in the pages of my book - and there were people scared to appear in it. There's even a woman in Selma, Alabama who was somewhat fearful. I suspect the people who would talk to me would tend to be less afraid of the consequences.

RG: You write that you "wanted to get the true measure of gay life" and go beyond big cities to where the majority [are]. Do you think you've succeeded?

NM: There are millions of gay people, and to interview a couple hundred for this book makes it presumptuous to say "true measure." I did try to get as representative a group as possible, to give me some sense of their lives.

I always felt there was so much more [to write about]. I didn't interview enough older or younger people - there are so many subgroups in our subculture; it's endless.

I was very happy with the book as a final product, but I always felt that I was inadequate, that there was so much more I could spend the next 10 years on.

RG: If someone gave you a lot of money during the production of the book and said, "Neil, visit those parts of gay America you can't afford to get to," where would you have traveled that you lacked the resources for?

NM: Alaska and Hawaii, for one. I wished I'd spent more time in Rocky Mountain states like Arizona and New Mexico, a part of the country I feel I neglected.

While I wished I went to more places, at a certain point, experiences do repeat themselves to some degree, and the differences are not that great. Ed White's States of Desire was trying to compare different parts of the country.

RG: He was also comparing what the title referred to - different states of gay desire, in that, beyond different geographic areas we might dwell in, all we really have in common is our sexual orientation.

NM: Other than big and small cities, I wasn't trying to compare things, like San Francisco versus Los Angeles.

RG: I was annoyed that both you did not really write much about gay Los Angeles. Why?

NM: Well, I didn't visit Atlanta or New Orleans or Chicago - and I barely visited Los Angeles.

You'll notice I devoted very little time or pages to New York. I used Boston, my base, as my Eastern city, because it was easy for me to do, and I knew it well. I also needed a West Coast city, so I chose San Francisco for obvious reasons.

RG: Why did you choose San Francisco as a West Coast city, say, instead of L.A.?

NM: I did spend time in L.A., but San Francisco is so important in the mythology of being gay. It has been THE gay Mecca since the late sixties when it was home to the sexual revolution and the flower children. San Francisco was so symbolic [in a gay sense] to me that I could not, in fact, not use it.

RG: Having asked this question, I feel I earned my fee for this assignment from my editor at EDGE !

NM: Some of the L.A. stuff was omitted [from the book], cut from a chapter on gay culture, a portion of which dealt with gay Hollywood. This section of In Search of Gay America, however, was not as strong as the rest of the book.

RG: I'm struck by your description of Boston as an "eastern city." I love Beantown and have gay friends there, but I don't view it as part of the East Coast. It's a very special city with distinct issues separating it from other northeastern municipalities. There's more academia there, more college students, much more liberal intelligentsia with strong roots in the movement than you'll find in other East Coast cities (with the possible exception of Manhattan).

NM: Possibly, but most large eastern cities have a fair number. Philadelphia does have Frank Rizzo, after all.

RG: He's been out of office for over a decade now.

NM: Boston is not that atypical, but one could argue about it, I suppose. Philadelphia perhaps has as many college students as Boston, and it also has its share of liberal intelligentsia. I do wonder if Boston is really THAT different. You may be right Boston has many ethnic neighborhoods. The grass roots here is not as liberal as you might believe; the intelligentsia does not dominate as much as you might think.

RG: A gut reaction to In Search of Gay America: you're a journalist writing at the peak of your form. Why don't we have more journalism like yours in the gay press? I rarely read human interest features like some of your book's chapters.

NM: I've worked in the gay press and the pay is low. At a certain point, gay journalists think [it's more prestigious to] write for the straight press [Money plays a large role].

The ADVOCATE is starting to feature more journalism [of this type] but I don't want to be critical [of them]. Christopher Street (a now defunct gay Manhattan literary magazine] has run some human interest journalism in the past, but it would be great to see more of it.

I don't mean to pat myself on the back here, but I'm surprised that somebody didn't try to write this book before.

RG: You use a word in your book I haven't encountered in a hundred years: "cosexual." What does it mean? Is this a sexual act I've missed?

NM: I got that word from [San Francisco fiction writer] Armistead Maupin it means both sexes being fully represented.

RG: Here's a question in a cosexual vein: nine years ago Ed White complained he had to travel to rural areas to socialize with lesbians. In the heart of Manhattan he found it difficult to find a place where lesbians felt comfortable socializing with gay men. In your book, there seems to be much less of that gender gap Is it narrowing?

NM: I do think that Boston is not typical in that some of its organizations, like Gay Community news have been really mixed as far as men and women are concerned for a long time. When I was in Miami, however, it seemed that men's and women's groups had almost no contact whatsoever; perhaps in the Hispanic sections there, this isn't so. But in many places those gaps remain pretty strong.

In In Search of Gay America, I argue that this gap is lessening [because] AIDS plays a role. Perhaps I'm being a bit Pollyanna-ish, but in many AIDS organizations, like Manhattan's Gay Men's Health Crisis [GMHC], many lesbians have gotten involved. I feel it's a lesbian role to be really nurturing to gay men, and gay men have really appreciated it.

RG: In many ways, that gender gap is understandable - I don't know a lot of gay men who are feminists, or a lot of lesbians who are political. I don't see lesbians or gay men sharing a lot in common in the natural order of things, other than their sexual orientation. If mother nature plays herself out, there's no natural reason for the two groups to cross paths together.

NM: On the other hand, because of AIDS, there are a lot of gay men who are much more political than they ever were before. Certainly most of the Boston lesbians I know tend to be very political. Isn't that true in other cities?

RG: I don't think so. Most lesbians are apolitical, at best. Regarding AIDS, gay Professor Richard D. Mohr [author of Gays/Justice] claimed recently that AIDS saps our political and moral strength, detouring much energy away from civil rights activism into, instead, basic human health care. Mohr was very pessimistic on our basic strength as a community.

I'm struck by how optimistic and upbeat your book is by contrast. You see AIDS catalyzing the unity of gay men and lesbians, for example, and working positive gains in other areas.

NM: I really did see AIDS as a major rallying factor. Even a decade ago as an editor at GCN, I noticed that many gay men didn't find anything to get them involved politically. [In contrast to AIDS] gay rights bills or repealing sodomy statutes are not big issues. AIDS as a life and death issue has brought into the gay political movement so many people who would never involve themselves before, like that gay Republican Boston computer business person I interviewed who would have nothing to do with gay politics - until a couple of his friends died of AIDS. Then he got very involved in AIDS activism, which wasn't necessarily gay.

I think that you're seeing many ACT-UP type groups moving into gay rights issues. Ultimately, AIDS is really strengthening the movement and I saw that all over the country. Like the guy in Bismarck, North Dakota whose diagnosis spurred his activism to found a state-wide AIDS organization. His energy overflowed to form a sense of community there.

RG: I'm fascinated by some of your reactions to people like Frank, the gay Republican in Boston. At one point [p. 63] you have quite a response to someone's "baby blue 1968 Mercedes Benz 280 SL." What's wrong with being "politically incorrect, shallow and spoiled," anyway? Is it a crime to drive or own a Mercedes?

NM: What's wrong with it? I came out of the sixties, where money and material things were bad, where values resonated around wanting to change the world. "Politically correct or incorrect," one can argue about, but I doubt anyone wants to be shallow or spoiled, do they? I believe many gay movement activists are idealists, and may look down on people who drive a Mercedes - at least the one I drove was 20 years old.

RG: Well, my first Mercedes will be a lavender one, with lavender colored sidewalls, I hope, and driven by a well hung chauffeur.

In your concluding chapter, you mention how spirituality and self-healing have blossomed among gay communities nationally. What do you attribute that trend to? No one would have foreseen that 10 years ago.

NM: AIDS has impacted by making people much more aware of their mental and physical health. I believe it relates to our coming of age as a community, taking ourselves more seriously, feeling we're worth something and that we can get our act together. There's a stronger sense of self and self worth that's out there which wasn't there before.

RG: An entire generation of gays came of age during the Stonewall riots [1969], and they're going through this midlife crisis which accounts for much of the revived interest in spirituality. Yet I'm describing an ongoing process which you can't predict the outcome of 2, 3, or 5 years from now.

NM: [Many gays of that generation] are going through a midlife crisis, and AIDS played a major role. When your friends are sick and dying, you really do reevaluate your role in life. One could talk in generalizations about how we're straightening out from sexual liberation, and what do we do now? Maybe we would have encountered this without AIDS. Still, I don't know where this crisis will take our community.

RG: You make the point in your book that the road to local gay political progress may lie in contributing to one's own community. You suggest that one way to soften up homophobic organized religions is for gays to remain active in those institutions, even when they're not easily tolerated. Assuaging homophobic religion may be the key to melting a lot of anti-gay bigotry.

NM: Yes! I really learned that when I toured gay America. Before, I always thought that to bother with some of these homophobic groups, like Roman Catholicism [was pointless], but when I traveled I realized religion was a major influence on almost every aspect of life. Clearly, religious attitudes towards homosexuality were one of the major stumbling blocks. If there is any way to break down their resistance, that's a key to making tremendous [political] progress.

RG: Whatever happened to Bob, the gay cop you met in Washington, D.C., who transferred to the San Francisco Police Department? You write that he was later diagnosed with AIDS.

NM: I don't know. He seemed in good health when I last saw him. I felt very conflicted about his story: here was a guy working for the vice squad, but I hesitate to claim he was "entrapping" gay kids or hustlers.

RG: I accept policeman Bob's explanation of things - hustlers frequently are a conduit for illegal drugs and they bring with them much crime.

NM: I've had very little experience with hustlers, but Bob had no conflict arresting them at all. I think he would have preferred another assignment where he was out dealing with more hardcore criminals.

RG: You didn't talk to many members of one of the biggest gay subcultures, gays in the military. Why?

NM: There's a Texas woman I spoke to who was a veteran, and Memphis' Black and White Men Together (BWMT) had a black naval officer who was very closeted.

Yes, that's one group of people I should have - and tried to do - more with.

RG: Neil, I don't understand why foster parenting, the right to rear children - or being barred from parenting them - is a gay issue. Frankly, I don't know a single gay man who even wants to have kids.

NM: The point is that if you do want to have kids, shouldn't you have the right to do so?

Yeah, but I don't view that as a gay rights issue. It's just a social or family question.

But it's a gay issue in the same sense being gay in the military is. We don't all want to join the army, but we should have that option if that's what we want.

If there's a gay couple or a gay single man who really wants to be a parent, the fact that he's gay should not stand in his way. Anytime you're blocked from doing something by being gay, it becomes a gay issue.

RG: Yes, but in the famous Massachusetts case mentioned in your book, it wasn't being gay that blocked those guys from raising kids, it was the Boston Globe's story about their being gay that forced the issue.

NM: Sure, if it had been kept under wraps, that would have been fine, but that's not the way things should be, right? Should you have to hide being gay in order to become a foster parent?

RG: We're not to the point Candide wanted, "the best of all possible worlds" yet, are we?

NM: There are gay fathers groups around and lots of gay men who want to be parents. There's a greater feeling that we have a right to be parents if we want to, and that being gay doesn't mean you have to forego having kids. [The Boston case] impressed me as being a blatant act of discrimination on the part of Governor Dukakis' [D-MA] administration.

RG: There is one element sadly lacking in your book: except for describing circle jerks in Manhattan, you don't really talk about sex much, or having sex, do you, Neil?

NM: That's a good point, but in so much writing about gay men sex has been the center of everything. I wasn't deliberately trying to play down sex, but I do think we are living in the late 1980's.

Sex is obviously a central part of the gay male experience and, increasingly, the lesbian one, but I really thought it was important to write about other aspects of people's lives: work, families, etc.

RG: Have your travels through gay America really changed you, Neil Miller, as a person? Do you have the same knee jerk reactions to things, still?

NM: I was going to say that I have a greater appreciation for diversity, but that sounds sentimental and hokey. I think I have more respect for different approaches to being gay, as well as different subgroups and lifestyles. I might have dismissed the gay religious folks before, but I have a new respect for them. I know now, too, that people in small towns certainly have to struggle more than people in big cities - those people are inspiring. I have a richer, wider view of things.

But I don't think I've gone through any great revelation after writing In Search of Gay America except that I feel more connected to people across this great big country of ours.