© 1987, 1988 Rich Grzesiak, all rights reserved.

This piece originally appeared in Philadelphia's AU COURANT in 1987. —RG

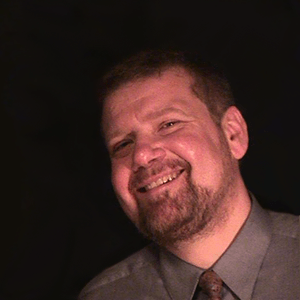

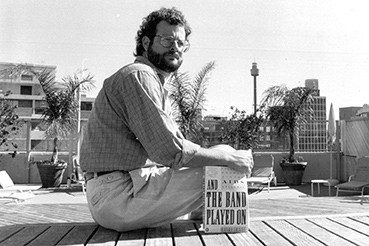

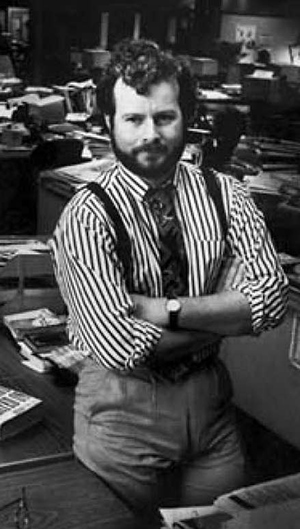

If you were to ask the American people what professional category they have the least respect for, I fully expect that the occupation known as "news journalist" will be close to the top of the list. That knowledge is not lost on San Francisco Chronicle reporter Randy Shilts, whose recently reissued blockbuster bestseller And the Band Played On [Penguin; $12.95/softcover] chronicles the devastating impact of the AIDS health crisis on the gay community. With well over a quarter million copies in print, its rights signed for a television miniseries, a recent monthly selection of the Quality Paperback Book Club, and fresh from scoring in the Top Ten of both the New York Times and Publishers Weekly bestseller lists, Shilt's And the Band Played On has rocketed him to the top of his career. Not only is he the most widely read (openly) gay writer in the United States today, but he's a top flight news journalist of incredible skill and outspoken dimension.

Shilts ain't shy, nor am I. During a telephone interview, I nailed him on the frightening topics of the health crisis and its potential for gay men, the sorry state of health coverage within the gay press, the depressing lot of fools who bill themselves as gay "politicos," and the even more dire subject of ethics in gay publishing — why, in other words we can't trust the gay news that we read, and why there are so many incorrigible dinosaurs sadly in charge of its production.

Sound like an exciting exchange? Read on, dear reader, read on.

Rich Grzesiak (RG): We all know how bad the health crisis has been for the gay community, so I guess I want to begin with a question relating to superlatives: how much worse is it going to get?

Randy Shilts (RS): I hate to be the one to say it, but I don't think our gay leaders are going to tell us. The fact is that we're not in the middle of the epidemic, we're at the beginning. What I can be definitive about with statistics is San Francisco. We know that we've got 35,000 infected gay men in this town and that figure is derived by random N.I.H. [National Institutes of Health] studies, which are as good as any in the world on this subject. So far, we've had roughly 4,000 cases. It would be safe to say that one third of these [infected] people will be getting A.I.D.S within the next four years, or, in other words, approximately another 8,000. So the problem will increase threefold. Probably it's going to get much worse here in San Francisco alone. Saying that only 12,000 will get AIDS is a relatively conservative observation. A more accurate prediction is probably on the order of 20,000.

RG: Given a worst case scenario, what is going to happen to the state of civil liberties in the gay community?

RS: I don't think that civil liberties are the most important thing. The gay political leadership is misguiding us by always talking about civil liberties. The most important thing for most gay men in the next five years, particularly in urban areas, is going to be just keeping sane in the face of all this suffering, because what I do know is going to happen is that we are going to be facing an incredible amount of untimely death.

We need to begin gearing ourselves for it psychologically as human beings. Now of course gay political leaders will discuss civil liberties all the time, and that's something to consider, too, but at that point we begin to get into the area of hypotheticals. Quite frankly, when I was reporting my first stories on the epidemic back in 1983, my first features were on how bad it was going to be. I had gay politicians who then urged me, don't write about this, don't put barbed wire around the Castro. They were then convinced that we were all going to be sent to concentration camps.

Today, as we near 1988, no one has put up so much as an inch of barbed wire around the Castro. I've been surprised at how little, genuine, society-wide anti-gay backlash there has been in the face of this epidemic.

RG: You obviously think about this subject a lot. Let's pretend that you're Jeanne Dixon for a few seconds. Looking into the future, at what point would you predict that we can expect a vaccine or something to arrest the terrible physical effects of the disease?

RS: There are two issues here.

First, the vaccine. Most scientists I talk to are getting increasingly optimistic. They just feel that the biological problems can probably be overcome. This clearly will not occur until the 1990's.

Secondly, there is also a lot of optimism in the area of treatments. A.Z.T. is a very clumsy and primitive drug with a lot of side effects, but it also shows that anti-viral drugs can be made.

The problem right now is, I think, political, as it has been throughout the epidemic, that we're not seeing determination for research on the scale of, say, the Manhattan Project on the part of the federal government.

I'm not even talking now about money because the money is, from what I gather, pretty much there, but we're not seeing any kind of intelligent coordination, or any kind of attitude evident among federal health bureaucrats that this subject is important and that all stops must be pulled in order to get adequate treatment. The N.I.H. Is still operating very much on a Business as Usual Attitude.

RG: As far as the gay community goes nationally, we're still talking about a pretty Balkanized group. I spoke to a friend several weeks ago who recently moved to Seattle and he reports to my horror that the bathhouses are still open there and doing raving business.

How do you feel about the fact that still, in various parts of gay America, the bathhouses remain open? In certain parts of the gay U.S., it's as if the 1970's are still going strong.

RS: I think that in 1983 the support for keeping the bathhouses open in the face of the health crisis was a mark of denial in the gay community. In 1987 I think that anybody who supports bathhouses staying open reflects insanity in the gay community, that it's absolutely, utterly insane to have these institutions open in the middle of the epidemic.

RG: And yet major U.S. cities still patronize and maintain their gay baths.

RS: What I want to do when I go to these places — and I always do it! — [is] to shake these people and say, oh my God, don't make the same mistake that we [in San Francisco] did.

In Seattle, I met with the leaders of the Northwest AIDS Foundation. I was very blunt and said that they should shut the baths down. I just wanted to tell people not to wait until half of your friends are dying before they move against these horrible institutions.

I think there's a political side to this as well. How dare we go and demand that the federal government pull out all stops for treatments and vaccine research, when we're not willing to do even so much as to close a business? It's a travesty on our part and politically stupid to boot. It makes us look incredibly irresponsible.

RG: Not so very long ago, in the days of my callow youth, I used to be fond of writing things to the effect that we should ship all of our gay political leaders to Managua — where they belong.

RS: I think I like the Nicaraguans too much to wish that even on them.

RG: Perhaps gay politicians should be donated to the Vatican where they can spend their hours developing encyclicals instead of ideology. In all seriousness, why is the American gay political leadership so worthless? Often those poor fools seem weak and divided, with no visible support from this community. Why?

RS: When I travel the first thing I do when someone confronts me with this observation is to challenge them to get involved, because as long as we have a lack of quality people involved [in gay politics], then the people who are involved will necessarily be[come] our leaders.

In the epilogue to And the Band Played On, I included a story about how various gay political leaders organized a sit-in at the White House so they could be photographed for their fundraising brochures. Later I ran into Vic Basile at a party in Washington, and he told me how hurt he was and how unfair my observations had been and how he had and would never do that. So I said to him, at least have a sense of humor, laugh at yourself! But his actions turned pious and self-righteous.

As I was leaving I was talking to a gay newspaper editor from Chicago and he told me that only recently an entire press kit arrived in his mail from Vic Basile's Human Rights Campaign Fund [HRCF] — bearing a wonderful shot of Vic Basile being arrested at the White House!

I though to myself that these are the people we rely upon to run our national gay rights movement?

RG: Well, I go back to my question: when you confront some of these so-called leaders with their constituencies, you find they actually represent next to nobody. Why?

RS: Well, the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force [NLGTF] has remarkably few members [to answer your question directly] I think that our leaders tend to be overly ideological. But it's not only their fault. I mean it is their responsibility in that they are overly ideological and they talk in ways that normal people don't talk. You must remember that it's not all their fault. A big part of the problem is that so much of the gay community remains so incredibly apathetic to politics. It seems that so few people in our community have opened up to the importance of politics in our lives, so they're reluctant to become involved in these gay political groups.

There are few writers in the gay press who have been as critical of our political leadership as I have. For all their problems I would still rather have any of the national gay leaders in Washington speaking on AIDS issues to Congress than I would have Jesse Helms [U.S. Senator, R-NC]. It is so crucial at this point that we need some gay spokes people in the national political process.

RG: At the high point of gay liberation, there was a slogan bandied about regularly, "the personal is political." But the problem with gay leadership is that they have interpreted that to mean that "the personal is ideological." That's what's turned people off from getting involved in leadership roles in our community and gay people in general.

RS: I find it persuasive the argument that the gay movement has to align with the Democratic Party. But I think some of our ideological ruminations get so incredibly abstruse. When you hear about the Board of Directors meetings at NLGTF, for example, they sit and argue for hours about the fine points of sexism and racism and all of these other -ism's. I know it even drives the staff members crazy at these groups. Then the staff members get so uptight that they drive everybody else crazy.

RG: Perhaps a good litmus test for these crazy politicos of ours was the disdain and apprehension that greeted former Congressman Bob Bauman [R-MD] when he came out.

RS: Some cities are able to incorporate many diverse points of view into their gay groups: gay Republicans in Chicago, for example, where some gay GOP members even hold leadership positions. It's funny how some cities become much more divided in their leadership groups.

A good example is how San Francisco divided itself up over the bathhouse controversy where a number of important gay leaders thought it was important to close the bathhouses. Rather than have an intelligent debate in the community on this, the debate evolved into the more leftist people attacking people with whom they disagreed on personal grounds. It's as if you can't disagree on a matter of principle in this community without facing these ad hominem attacks, a very immature form of debate.

RG: Let's move beyond the frequent bankruptcy of gay political dialogue and talk instead about our lovely gay press. There is this charming publisher of Christopher Street and the weekly New York Native, one Charles L. Ortleb, who recently urged his readers not to purchase And the Band Played On because it and you were anti-gay. Why would he make such a statement?

RS: Ortleb is simply a lunatic. I think most people in the gay community recognize his bleatings as the result of probably some viral infection of the brain [sic]. I would suggest though that what's interesting about Ortleb's comments was the tact of saying that I could write what I did — being critical of the gay political leadership — and that that reflected my hatred of myself for being a homosexual. You know I've spent the last 10 years of my life as a television reporter and been openly gay as an author and journalist, a sometimes barely prominent member of the gay community, certainly more so than what Ortleb has [done]. How dare he suggest that I write what I write because of some psychological maladjustment of my being gay? He hasn't lived one day of his life the way I have for the last 10 years in terms of being openly gay.

RG: There is this truculent attitude propagated by the New York Native that somehow its A.I.D.S journalism is the sine qua non within the gay press today.

RS: Well, the Native did a pretty good job from 1981 to '83 — then they went crazy. Then they started covering the swine flu theory, more recently the syphilis theory — any theory that appears it might be a conspiracy has credibility with that paper.

RG: Publishers like Ortleb frighten me. How is it that someone with his remarkable ethics is even allowed to publish a gay newspaper in this country?

RS: In America, that's freedom of the press, and apparently he has someone who bails him out of debt. It's sad because at one time the New York Native had more credibility with the medical community than any other gay publication now they've pissed all of that away and it's just a big joke.

RG: How is it that Larry Kramer is allowed to get away with his shenanigans? He brings a valuable message, but it's corrupted through and through by his anger and vitriol. How would you evaluate his role in the AIDS crisis?

RS: Well, I think Larry realizes that his own style effectively worked against his ability to communicate his message in some ways. Larry is just like a teddy bear, once you get through that angry exterior of his. I was struck by the fact that from the very first moment I interviewed him, it was almost as if we had to have an argument just to develop a professional relationship. Another interesting factor I discovered in my research is that, even among people in New York who despise him, most will admit that essentially he was right all along.

RG: One of Kramer's arch enemies during the early days of the health crisis was my late friend, the Advocate health correspondent, Nathan Fain. How would you evaluate his reportage?

RS: He actually did do a good job. In preparing my book research I frequently found it useful to refer to his articles because he frequently would cover a point that deserved to be on the record which you couldn't find anywhere else. If I have a problem with his journalism, it was that he could have done more in taking brave stands in that his reporting wasn't "contrarian" enough.

RG: In the gay press, the Advocate is the largest single publication. How would you evaluate their reportage of the health crisis over the years?

RS: Early on, it was horrible. Up until 1983, they didn't do anything, you barely knew that they were even cognizant of the epidemic. After hiring Nathan Fain, they started getting better and on the whole it's a good publication today.

If I were the editor/publisher of the Advocate today, I would cover AIDS differently. I would simply make up my mind to do everything in my power to win the Pulitzer prize for AIDS coverage, hire two reporters for just that purpose full-time, and cover it to death.

RG: How would you assess their current coverage of AIDS, specifically the journalism of Michael Helquist?

RS: Well, I'll give you one example of the sorrier aspect you see in gay newspapers. Last fall he did a column about all the different AIDS newsletters you can get and included a newsletter that he edits and that's what he gave the most space to. He didn't mention the fact that he was the editor of it, however. I really find that disappointing.

RG: Ethics in the gay press: a penny for your thoughts

RS: I think that much of the gay press would be a lot better off if it paid attention to whatever standard of ethics is promoted by the Gay & Lesbian Press Association. This year, as I've had less time to devote to my work at the Chronicle, I have turned on my colleagues to what I consider to be one of the most valuable tip services that I have as a reporter, namely the three gay newspapers here in San Francisco. The fact is that they provide a lot of good raw material to reporters at big newspapers to follow up on.

It's so disappointing, though, in that the word from most of my colleagues is that you can't trust an awful lot of what's said there. Their and most gay newspapers' political coverage is like reading Pravda. First, you have to figure out what the personal bias of the reporter is, then filter out what's real and what's merely the parroting of the party line.

That undermines the credibility of these newspapers and it limits their acceptance both within the gay community and among straight people. The gay press would have a lot more influence on policy both local and federal if it was a credible press. You don't need a huge circulation to have influence; you just need to be telling the truth and to have people worried about how they're going to look if they get reported on. Nobody's going to worry about what they'll look like if they're written up negatively in the gay press because it's always so biased

On the whole, though, I've talked to just about every gay newspaper in the country during this current book tour. I'm coming to believe that a new breed is coming to the fore and, hopefully, they'll be influential enough to push the dinosaurs right out of the business.