© 2021 Rich Grzesiak, all rights reserved.

About a dozen years ago the novelist James Leo Herlihy wrote a book called Midnight Cowboy. Other writers followed with works like Cruising, an examination of the underworld of violence and sex; Butterflies Are Free, a character study of male hustlers on the road to self-destruction; and much, much later, a slew of titles ranging from the abysmal if not well-intentioned Superstar Murder (midnight Manhattan mayhem among the twilight people) to the sero-religiose Faggots with its almost theological evocation of Bad Boys Gone Wrong.

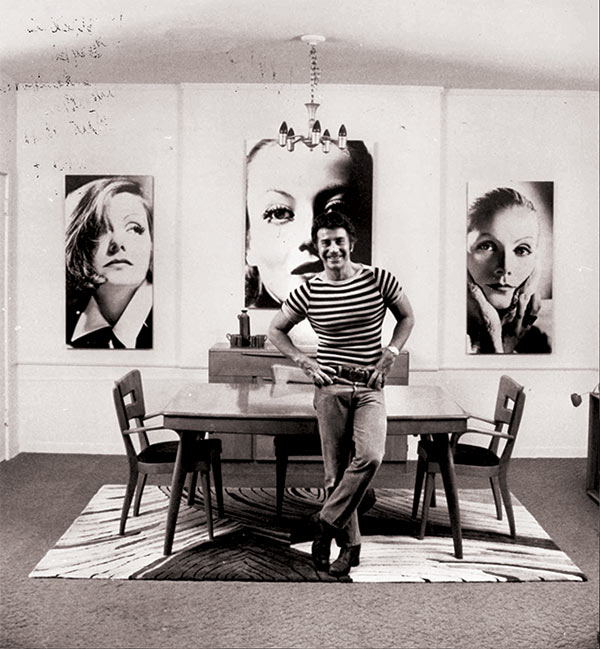

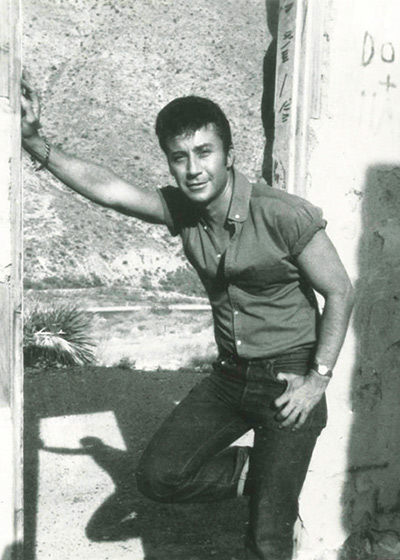

To John Rechy these books—and many, many others—constitute ripoffs of areas that he originally helped to put on the map. With his Decameron-like City of Night, in 1963 (Grove, $1.95), a gigantic new vista opened to American homosexual writers. City of Night tracks the wanderings of a male hustler across the American continent, and does it better, more movingly and literally, than any other writer can or has to date. If a literary generation can be said to have taken its cues from any one book, then City of Night is a strong contender for such an honor.

Rechy's later works expanded his evocation of the urban world. Numbers, (1967; Grove, $2.95) follows a hustler named Johnny Rio through Los Angeles' Griffith Park. When initially released, many public libraries stacked it in special, limited access collections so that the general public would not be offended by the alleged "pornography" of the book.

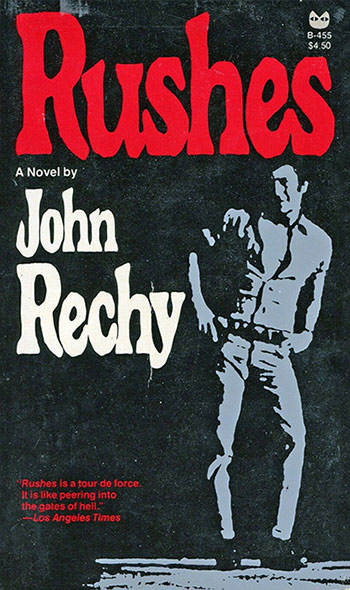

This Day's Death novelizes police entrapment in America. One reviewer called it "the most moving protest against the garrison state ever written." Rechy's other works include Vampires and The Sexual Outlaw: A Documentary (Dell, $2.25). Rushes (Grove, $10), his sixth and most recent novel, explores the world of a leather bar in New York. Rushes has debuted to very good reviews.

If a voice may be said to smile, then Rechy's does. He is best described in his own words:

"My background is mixed, Mexican and Scotch, but I learned Spanish before I learned English, and we continued speaking Spanish so I was really much more firmly in the Mexican culture than in any other. Mine was a mixed background; I belonged to neither culture too clearly.

I was greatly affected by many of the classical writers, certainly Dostoevsky, the form of the ancient Greek tragedies, the redemption of the gods. In fact, a chapter of City of Night is written as a Greek tragedy, especially. Philosophically, Nietzsche continues to be a giant in my life. In later years Camus became very important and continues to be, despite a bit of ambivalence. With the contemporary writers, Joyce, Proust, Faulkner, Tennessee Williams, and the rest were major influences.

The structure of so many of my works is absolutely classical. That always amuses me so much. When City of Night came out, the criticism was that a dumb hustler had managed to stumble onto a form. Well, I do play dumb hustler on the streets, but when I'm writing I'm not dumb, anything. Sartre and Kierkegaard have influenced my from, and yet you have no idea how many people think I've never read a goddam book.

People constantly evaluate me as a dumb hustler, especially if you look like their conception of a dumb hustler. I play it, I play their role. Sexually, let's face it, they're one of the choice roles. That also gives (me) the upper hand in that I'm thinking there's more going on here than you expect—it'll end up in a book.

I am currently writing a play with a friend of mine, the first collaboration I have ever done. That is exciting and, I hope, prophetic."

Rich Grzesiak (RG): When I read Rushes I remember thinking to myself that the dialogue was so good that the writer must have initially crafted it as a play, thrown that away and then decided to extend a novel from it. Is that how Rushes came to be written?

John Rechy (JR): That's close to it. I did a play version of Rushes and then the novel seized me, and now the play version of Rushes is finished in a certain form and off to my agent in New York. It did indeed begin as a play, and the novelized version of it just seized me, so I went on with the novel. But it is indeed a play. I would like to see it staged as a Mass, of course not with the vestments but in the costumes of the thing and with the ritual of the Mass—that has always struck me in the sexhunt.

RG: So many of your characters are glittering glaciers—they seem to move with a blistering anger that is very discomforting. I think of Johnny Rio in Numbers or Shell in The Fourth Angel. But to my experience these characters seem to be predominantly urban types. Do you think that people are moving into these urban clone-type personalities to a degree that they were not, say, 10 or 15 years ago?

JR: Oh, I definitely do. I think that the threat to nonconformity is at its greatest now, and paradoxically and ironically and sadly I think a faction of the homosexual world is providing the lead toward conformity. I mean conformity and not nonconformity, and I think that we are the vanguard of the new conformists. This of course is one of the many themes in Rushes, though it is a minor one. I think that we are in danger on two fronts, but a very subtle one is from the inside, where we are confusing heterosexual imitation with liberation and creating new outsiders within our own ranks. That's why I think the homosexual at this point is providing potentially the most danger to nonconformity and to creativity. You know, we're not producing, the art and writing is not coming out of the subculture.

RG: But I see us as emerging as "blissninnies" with neither colorful differences nor ethnic variation, Manhattan clones...

JR: Or Los Angeles or Santa Monica ones. That's why I say we are providing the major opposition to what has been endemically our richness. Now we are questioning this.

RG: The writing disturbs me in that it's urban ghetto-oriented. In order to have a successful gay novel these days you have to be dying from drugs in New York or you have to be on someone's couch in New York and be capable of writing about that experience. That's a dangerous trend.

JR: But, Rich, let me say that I disagree with that entirely: in fact I find the danger on the other side. But on that point, you see, I lament the fact that I'm often criticized for my seamy writing about a tiny segment of the homosexual world and according to this (criticism) the majority of us are having a happy tizzy every moment of our lives ... the "blissninny." I was talking to Christopher (Isherwood) the other day and he was telling me that the word is not original with him. One of the so-called flower children of the Sixties said to him, "I want to be a blissninny!" And you see, too many of us are acting like blissninnies. And I think too that we are confusing the wish (to be happy) with the fact and that we are the only minority that is thrusting this on the artist. We are saying to the artist, give us a positive role model which very often means heterosexually oriented, and tell how happy we are. That's bullshit.

The artist has traditionally dealt with what is dark, what is in need of exploration. And our horizon, despite all the gay parades, is a very troubled one. We've got a lot of problems. And granted that, as I very often say, you can't criticize the homosexual world without implicating the heterosexual world much more, nevertheless, at this point in our development we're not dealing truthfully with our problems. And people say that I present a tiny segment of the homosexual with it and say, yes, that's true, and now I say, bullshit, that's not so—it's a vast segment of the homosexual world.

RG: Artists do not possess the entire responsibility for this exploration of our world. I place a great deal of blame on the gay press which is accustomed to puffing novelists, photographers, politicians and lifestyles. It never wants to descend into real problems: drugs, booze, sex, you name it. To write about those things is to alienate the middle-class which buys the newspaper and thus permits it to grow. If you do a long piece on alcoholism you're not going to thrill the bar owners who advertise in the newspaper.

JR: That's right. We're being forced, the novelists, too, and all the artists to be in a sense apologists for our world because I think there's a great confusion as to what is really negative and what is really enriching.

RG: What is shallower than artists becoming nothing more than shallow journalists?

JR: Absolutely. That's why every one of my books continues to arouse such anger.

RG: But at the same time, ironically, we have to begin to describe our world because it never existed in the literature before, or if it did exist it sank so deeply into oblivion that few were aware of it.

JR: That's very true, but we do have to discuss it truthfully, you see. The fact that we now have the freedom to discuss it doesn't mean that again we are going to create the literature of the ninnies. We are going to have to explore very deeply what's been done to us and what we are doing to ourselves. I feel that in Rushes that was one of my main intentions. That is always so embarrassing to say because we have couched all these things in reticence. But I truly do feel a tremendous responsibility to young homosexuals. People say, well, what would a young homosexual reading one of your books think. But the point of the matter is books like mine can act to purge the landsacpe by exploring what is negative and vaunting what is positive and saying "cling to this" and "let's explore this." I like to think I have made a contribution to the future of the young homosexual. It's a very sad generation that's coming up, for they've inherited all our horror without the knowledge of what created it.

RG: Or, as you would put it in Rushes with no "concept of redemption."

JR: And "no substitue for salvation"—those phrases recur in almost all my books. So you see we are at a very dangerous point and the artist has traditionally explored the depths. It's not a small segment I'm writing about, it's a major segment—the bars, the increasing sadomasochism and things like this.

RG: As a writer, do you feel boxed into a category? When you write fiction for the 1980s, do you feel you have to focus exclusively on homosexuality and your experiences, almost as if you've been ghettoized by the very literature you've written to liberate people?

JR: Not exactly—that is really a two-part answer. What I resent is getting characterized as that I cannot tell you what it does to me to be called a gay spokesman. I do not consider myself a homosexual novelist. I consider myself a writer, a very good writer, and I write about the homosexual experience. I don't feel a pressure to do it. I resent being dismissed as just a homosexual writer whose validity is based only on writing on homsexuality. I'm not writing for homosexuals any more than I'm writing for heterosexuals. I'm writing for people who read, and especially with Rushes—I don't know how one can call it a gay novel, "gay" in any sense of the word. To me that's where the word "gay" just gets so much in the way that I really detest it.

RG: When I read Rushes I found it a very difficult experience in that it struck so deeply at home. It took me weeks to write a review of it, to sit down and really express my feelings about it.

I am very glad for that reaction, even if it was a negative one in the sense of being made uncomfortable. Rushes is for me a book that puts us in a metaphorical crossroads. In which indeed the choice is between decay and self-destruction, and moving away: decay and self-destruction being one front, or moving away to a true liberation with our own specialness. That's why I put it at land's end, into the water. It's a very symbolic book.

You know I move increasingly toward structure for meaning. This again is one of the things I resent so much when I am thought of as being a clumsy writer. I so consciously structure a book. In this book: you know. I really wrote a Mass. There are equivalents, of course, to the priedieux (kneelers used in Roman Catholic churches), and the incense becomes the poppers. The Stations of the Cross are the pornographic images, and even the commentary on the Fifteenth may or may not be the Resurrection, and that of course is equal to the 15th chapter (of the novel) which describes the (climactic) disorder.

The religious symbolism has been there, unseen by most people—although there was a woman who recently did a doctorate on the religious symbols. Yes. I am getting several doctor's theses now. I don't know whether that should please me or not. For a very long time the Texas Institute of Letters kept me out. Every year my name would be put forth for membership and for almost 10 years they kept me out. They finally invited me to become a member of this "august body"—soi-disant, you know—and I thought, oh shit, should I be happy now or saddened by this? Is something happening that I don't want to happen? So I don't know how I feel about the Ph.D. theses. I never want to stop being dangerous.

RG: Is sadomasochism really more predominant in our community today, or has it just been written about to a degree that we're more aware of it than we were before?

JR: I would say that it is definitely an increasing tendency. I'm not criticizing sadomasochism from any moralistic point of view but from (the viewpoint of) somebody who has known it very, very intimately and still does. But not only from that—reviews of Rushes are appearing in virtually all the slick homosexual magazines, and I've been looking at them—you know, Blueboy, Mandate, all of them—for some time. There used to be only one magazine that was overtly sadomasochistic, Drummer, and I was astonished that every single one of these, without exception, has a whole feature that is S&M-oriented. I am thinking of one that in point of fact carried an excellent review of Rushes and a feature story that had this naked young man being brutalized by a booted man. And it is such an irony—there is this review of Rushes with its point of view of sadomasochism and it's in this magazine that has a feature on the brutalization of a person, of one homosexual by another. I think it is the main interior problem that we face.

RG: What was the queens' description in the '60s for what S&M stood for? Slippers and makeup?

JR: I haven't heard that one before. There's a film that I've seen called "The Army of the Lovers, or the Revolt of the Perverts," it's directed by a German named Rosa von Prauheim. There's a remark from a very effeminate drag queen or transvestite to the effect that when we rebelled at the Stonewall in 1969 we had no idea that our freedom would be six hundred leather bars and joining the Army (laughter).

That's the main confusion that we're having as to what really is freedom. Is it heterosexual imitation? Absolutely not. Is it moving into punishing each other for homosexual sex and enacting the rituals of our oppression? Absolutely not. So I think it's time for questioning things; and that's what I meant to do in Rushes, simply to bring up questions.

To sum up, S&M is growing, and it's something that we don't want to face. You know sadomasochism is not restricted to the leather bars. I can be cruising a chic area of Los Angeles and I can say conservatively that 50 per cent of the pick-ups that are made there will end up having recognizable overtones of S&M sex. But the climate in Los Angeles—I love its whip, its breath.

RG: But to go back to another subject: there are so many religious groups like Dignity (for gay Roman Catholics) that attempt to mitigate the guilt which so many religious gays feel.

JR: To Dignity I react with personal sorrow, and to any of the other religions I react with anger. I wish in an ideal world that we could stop our flirtation with religion which has put us where we are, that we would stop our flirtation with the kind of condescending politics which has, again, put us where we are, and that we would stop our flirtation with psychiatrists; who have been major oppressors. Instead we are constantly trying to be exceptions to these three oppressors. We are saying psychiatry is fine, except when it says that we are sick, religion is fine except when it says that we are sinners, and the law is fine, except when it says that we are criminals—instead of questioning the institutions.

So you have this syndrome of the establishment homosexual who is really an oppressor himself. That is one of our main problems. In San Francisco, Los Angeles, and New York the homosexual is becoming a new type of oppressor; he confuses that with liberation.

I don't subscribe to the idea that if you attack an institution you automatically have to propose an alternative. I think these institutions that we've discussed are decadent enough, that per se, the attack should be on them. What will happen from there will be determined once the thing is vanquished. I truly do believe that religion is such a clearly oppressive element of power in our lives that one doesn't have to have an alternative. When you have an obvious tyrant like Hitler you don't say that we're not going to destroy Hitler until we have something to replace him with. There are certain things that are in a category by themselves, and I think religion is one, and the current trend toward psychology and psychiatry that makes us all the same is another. You just say that these are fucked, and these have to go, and then you move on. With religion—well, there is a very powerful thing there; I would return to the Mass in Rushes.

RG: The more you write, I think, either the more dangerous you are going to become or the more traditional.

JR: I hope it will be the former; I definitely hope it will be the former.