© 1988 Rich Grzesiak, all rights reserved.

Notes on Living Until We Say Goodbye: A Personal Guide

You're diagnosed with AIDS?

You know friends who have died of AIDS? You know people dying from AIDS right now? Your family has caused you heartbreak because you have AIDS?

West Virginia native Lon Nungesser ["Lonnie Gene Nungesser"] answers yes to all the above. He's a tough expatriate of the Ozark Mountain region who's wrestled with all the many problems people with AIDS [PWA's] confront. Professionally as a psychologist he deals with many different kinds of suffering from terminal illnesses—not just AIDS

A Southern Baptist by religion and a fervent advocate of exercise (he lifts weights and bicycles regularly), thirtyish Nungesser is no run-of-the-mill health care professional. He's a sexy man who cares deeply about people struggling with impossible situations in the midst of this epidemic.

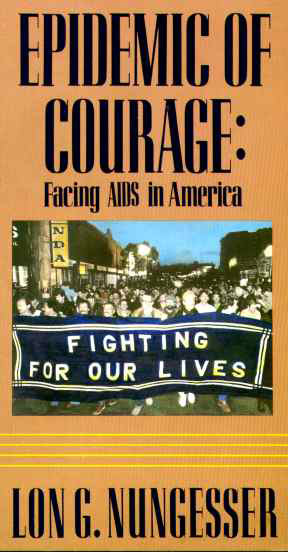

Nungesser has two books on the street for people dealing with incurable illnesses: Epidemic of Courage: Facing AIDS in America, recently reissued under the Stonewall Editions imprint [Saint Martin's Press; $7.95/softcover], a series of interviews with PWA's and their families regarding survival in the wake of turmoil; and Notes on Living Until We Say Goodbye: A Personal Guide [Saint Martin's Press; $14.95], a powerful compendium on how to live with a terminal diagnosis written from his own hard-won experiences (although a PWA, he's survived some five years since diagnosis).

"It is your life! Live it now!" claims Nungesser. I talked by phone recently to this honorably discharged U.S. Coast Guard veteran and Stanford University doctoral candidate about the very serious issues of AIDS and survival. Here's how it went:

Rich Grzesiak (RG): Your book Epidemic of Courage is probably one of the toughest, most sober-minded, serious books ever to grace the shelves of a gay bookstore. Was it especially difficult to conduct interviews for it?

Lon Nungesser (LN): Surprisingly, it wasn't. Often, the people I interviewed were feeling a lot of despair and I almost always left them laughing. It was difficult afterwards when I assimilated what I heard—you have to realize I conducted these interviews approximately four months after my own diagnosis. To see what lay possibly in the future for me was extremely confronting.

It was also very helpful because I began to understand how important it was to carefully select my social network. I began to comprehend how very, very critical it was for my family to have an excellent understanding of what I was going through and a concrete grasp of the facts about the illness apart from my sexuality. They're natives of the Ozark mountains and very, very conservative. They're very proud of my religious background and it was extremely difficult for them to deal with my being gay. My first book, Homosexual Acts, Actors and Identities, was the first gay psychology textbook. To put it mildly, they were mortified by its release. When Epidemic of Courage came out, they were a little more accepting I dedicated my latest book, Notes on Living Until We Say Goodbye, to them, and they send me to these interviews with their blessings.

RG: In looking back on the production of Epidemic of Courage, what was the most poignant moment you experienced?

LN: It occurs during the interview chapter entitled "Gertrude Cook, A Mother's Love." When Gertrude told me that David, her son, died in her arms and he was happy, I wept with her. She was such a loving person; she had so many incredible things to say about prejudice. She taught me a lot about how important it is to reconcile conflicts within a family before the death of a loved one.

It's unnatural enough to have a child die before a parent does, but to be unable to resolve issues loaded with conflict before death causes the grieving process to be just devastating for parents. I've invested a lot of emotional energy in my family just to make sure that when I'm gone, they'll have very good memories.

As you read through these interviews, you might find them a little dry or you won't understand how I got people to talk so openly. What's missing is all the sharing I did first [which enabled me to] establish a level of disclosure I expected from people.

RG: Can you estimate how many PWA's you interviewed for Epidemic of Courage are still alive?

LN: Sadly, only one.

Of the PWA's I interviewed, Jeff wound up having a leg amputatedhis death was very gruesome. The last time I spoke with John his Kaposi's sarcoma (KS) was aggressing very rapidly and he was on a decline. Dan Turner is still living and having a pretty tough time.

I interviewed two lovers, Bobby Reynolds and Mark Wood, on Valentine's Day out of respect for their bond. Of the two, Mark was definitely healthier but, ironically and sadly, he died before Bob. Going to Mark's funeral was probably one of the most difficult experiences of my life. Realizing that my own partner might predecease me was an overwhelming confrontation.

I talked with Bob Cecchi when he was recently diagnosed with AIDS It was very upsetting for me because I always thought Bob and I were brothers fighting the same war on distant shores. He was diagnosed with A.R.C. about the same time I was diagnosed with AIDS five years ago. He has the same T-cell ratio I do; for him to suddenly come down with several very serious opportunistic infectionswas pretty confronting.

RG: When my friend Patrick succumbed to AIDS over a year ago, the wave of depression and sadness that overwhelmed me was just paralyzing. It took me many months to deal with the very possessive feelings I built up about him. Even today, it's hard for me to think about his death.

LN: This experience is being repeated daily in the gay community. What advice would you give someone as they work through feelings of grief and possessiveness concerning a loved one?

To hold onto the finest memories you have about those people and to do something similar to what I've done regarding a past lover who's died: I saved a memorial card from his funeral and put it in a 50 year old recipe box that has a bronze rooster on the outside. I cherish this object; he and it have a very special place in my heart. I don't dwell on negative things about my loss but I feel I embrace instead all the things I learned from knowing him.

RG: Somebody reading this publication may just have been diagnosed with AIDS: is there some general advice you'd give such a person?

LN: I tell people just diagnosed to take it one day at a time, to slow down because you don't have to make all your medical decisions right now. Probably the most important single statement I could make is that a terminal diagnosis is an event to be adapted to, not a death sentence to be compliant with. Don't give up hope. This advice becomes a conversation that's quite lengthy when I speak with someone who's just been diagnosed.

Most people don't believe that hope in the face of a life threatening situation is legitimate—they think it's denial. They don't understand we can nurture in ourselves the simultaneous acceptance of hope and denial in the face of death. Just to accept our mortality is a very freeing experience, and a great deal of self-knowledge can be attained after one realizes death is coming early, but it was going to come anyway.

I cannot sufficiently stress the need not to make all one's medical decisions right away. A lot of people become very desperate and go right into the first experimental protocol the doctor offers them. I ask patients questions like, "How was the diagnosis put to you?," "How were the treatment options put to you?," "Were treatments explained in terms of probabilities of death or survival?"

After reading a lot about medical decision making, I've learned that the way a doctor frames a decision can influence the way you make one. When I refused an immuno-suppressant treatment for KS, an internist said to me, "What have you got to lose?" When choices are communicated to you that way, you've really got to take a very serious look at what the doctor's role is in deciding which treatments to pick.

I also encourage people to develop a conceptual model of their treatment as being not either/or but both/and: it doesn't have to be either A.Z.T. or wheat grass juice, it could be seen as both/and. You can do both of these things and they will work out just fine. In fact, that's the best way to live. I wish all of medicine were integrated like this.

RG: Does a PWA have a right to euthanasia?

LN: Absolutely.

RG: If a PWA came to you professionally and said they'd been thinking very seriously about their situation and they weren't sure they wanted to live through these experiences, what advice would you give them?

LN: Since I work with terminally ill people, I've experienced this with several individuals and not just PWA's. A female attorney with terminal breast cancer came to me recently with just this problem. I refer people like her to an organization called the Hemlock Society. I also stress the importance of considering the impact of euthanasia on the rest of the family and loved ones. I want to make sure they're not really hopeless.

I believe there's a certain point in any setting where euthanasia becomes a legitimate alternative. It's your life and you should be able to make these kinds of decisions. However, if somebody who's just been tested positive for the AIDS virus calls me and they have a suicidal ideation, that's a totally different story. In those situations, I am legally obligated to make sure they're protected from harming themselves.

The approach I generally take is to make sure you consult a mental health professional, see an attorney, and get your directive to physicians in order. That way, when you're admitted to a hospital, you won't be hooked up to life saving equipment. Once you're hooked up, they can't take you off, even if you have a directive. It's too late. They can't undo what's already done because it's against the law.

RG: One often hears anecdotes about the families and lovers of PWA's struggling over funeral arrangements and legal estates. How important is it to have a will in these circumstances? Are wills an effective means for controlling one's final days?

LN: Absolutely. One week after I was diagnosed with AIDS, I went to my attorney because there was a conflict in my family over cremation. I have made all the arrangements and my family will have no say in this matter. Since then, I've resolved this matter with my family; they agree it's probably the best solution for this very uncomfortable problem. Even in the face of a resolved situation with family and loved ones, however, the legal paperwork should be done; it's critical.

RG: Are you hopeful a cure for AIDS will be discovered?

LN: I'm always hopeful and I'm very careful not to tell people, "Don't take A.Z.T." or whatever. On the other hand, from my own personal experience with AIDS, I've seen a lot of drugs come and go, and I've seen a lot of my friends come and go. When you look at it in a hard and cold way, I guess somebody has died while taking just about every drug. So it's pretty hard to say these experimental drugs are killing people.

I do wonder in my heart of hearts what would happen if more people, especially those with just KS like myself, didn't do immunosuppressive treatments for these symptoms. It's pretty clear I'm in remission: I had 14 pretty large tumors upon diagnosis five years ago. Now I have one tiny little spot, smaller than the size of pencil eraser on my calf, and that's all that's left of it. I have no other opportunistic infections. I've done absolutely no treatments.

I do not believe that within the next five years there will be a cure, not for cancer in general, nor for this specific disease of AIDS

RG: One encounters reports in all types of media of discrimination against PWA's.

LN: The kind of discrimination I see has changed. It isn't as blatant; it has a liberal facade to it. It's become almost chic now to have a gay [PWA as a] friend, yet the discrimination manifests itself in other, peculiar ways. It's very hard to establish new relationships with people because they deal with you with the expectation this friendship won't last. I consider this a form of discrimination.

People who consider a terminally ill person of any type to be as fragile as a butterfly and then treat them so—that, too, is a form of discrimination.

I've had people, even doctors, stay at my home, claiming to be not very fearful. I take extra precautions very frequently just to make people feel comfortable. Even though I use rubber gloves while preparing food, there's one person I know who's very uncomfortable eating meals at my house.

I think what's going to change discrimination at this level is the almighty dollar. After a while, they just can't afford to take PWA's out to dinner anymore.

RG: Would you like to comment on press coverage of AIDS?

LN: With the exception of And the Band Played On, most media coverage is less sensational, negative, and dramatic than early in the epidemic. What I would like to see is more coverage of long term survivors. I believe there are a lot of PWA's out there who have been alive for quite sometime.

The best thing journalists can do right now is to tell the stories of bravery and strength people are demonstrating. It's so important to report on having places we can meet, and on how our relationships can be sanctified in ways that are more meaningful and legal. If anything comes out of this epidemic as a political achievement on the gay community's part, it should be our acting more aggressively to legalize gay relationships.

RG: When I interviewed Randy Shilts (And the Band Played On) in December of '87, he told me that he thought that the idea of civil liberties in the gay community had been overemphasized: "Gay political leadership is misguiding us by always talking about civil liberties. The most important thing for most gay men in the next five years is going to be just keeping sane in the face of all this suffering, because what I do know is going to happen is that we are going to be facing an incredible amount of untimely death. We need to begin gearing ourselves for it psychologically as human beings." Is Shilts right?

LN: No. Political leaders must continue to insist that civil liberties and gay relationships must be protected under law. Politicians do not have the responsibility to help us deal with emotional issues.

One of the greatest disservices Shilts did was to target Gaetan Dugas as the person who brought AIDS to America. He should have tracked a member from each risk group instead of making it appear that Dugas brought AIDS to America.

RG: Do you favor closing the baths?

LN: Absolutely not. Government ought to develop panels with gays participating on them to decide how the bath houses should be properly used. I think government should purchase the bath houses and turn them into education centers and health spas. We need places where we can go, learn about what's happening to us, and nurture our self knowledge as we go through this.

RG: I wonder how gay bath house owners would respond to the prospect of nationalization of their assets.

LN: Well, it would be financially better for them to sell their property to government than to close down.

RG: In your professional contacts with PWA's, are you aware of any who engage in unsafe sex practices? How do you deal with such a situation? How common a problem is it?

LN: I find it a very uncommon problem to find PWA's who have anonymous sex.

In fact, a person who was massaging me not too long ago said, "My goodness, you certainly don't have a problem getting a hard-on! You're one of the few PWA's I massage who get so easily aroused!"

Most of my sexual instincts are unimpaired. I often endorse something I call masturbation therapy in order to encourage positive sexual self-esteem in PWA's. I think it's very important to maintain a positive image of yourself sexually.

RG: You've raised a topic the media doesn't like talking about, that just because you're a PWA doesn't mean your sexual needs decline.

LN: They change sometimes and your intimacy needs become much more critical than your desire for an orgasmIn that sense there's a change, but the sexual need certainly remains. The most important aspect here is not how many orgasms a person can have but the fact they still have a positive image of themselves—that they don't see their cum as dirty and poisonous!

However, I will say one thing on the subject of pornography: it's derogative, pejorative and demeaning to see unsafe sexual acts that kill people portrayed in pornographic works. Watching unsafe sex in pornography does nothing to show us how to care for one another.

RG: How would you evaluate the degree of gay volunteerism for PWA's?

LN: It's probably one of the most beautiful things to come out of the epidemic. We have created a brotherhood and sisterhood that is very, very powerful and will serve us for many years to come.

Editor's note: Rich Grzesiak dedicates this feature to Patrick and Christopher, two friends who died in 1987 and 1988.

This interview originally appeared in 1988 and 1989 in Philadelphia's Au Courant and West Hollywood's Edge Magazine.